Entries from September 2010

September 3rd, 2010 · 4 Comments

I first have to state that this is a blog about people watching, not art or museums. My trip to the Tate Modern confirmed something I’ve suspected for a long time: I just don’t get modern art. I don’t get the art itself or the the people who do. For the most part (there is some modern art I find appealing), I found that what I saw was trying too hard to say something and in the end, was communicating no message whatsoever to me. Yes, paint splatter looks interesting, but to quote the seven-year-old girl who walked by me, “Daddy, I can do one of these!” One exhibit, a series of pieces by Agnes Martin felt as if the artist looked as if someone had taken a bunch of American Apparel t-shirts, made them very large, and put them on a wall. I just could not get a sense of “euphoria, contentment and memories of past happiness” (for more go here) from a series of stripes.

Taken from the Tate Modern Website

Once I had realized that I was not going to be spending my afternoon sunk into an emotional pit inspired by paint splatter and lumpy statues, I turned to people watching. This activity confirmed what I’ve long suspected: modern art officianados are the same no matter where you are. There seem to be two breeds: those who actually know what they are talking about and those who do not but wish to appear like they do. The first is a fairly respectable bunch. They tend to be middle aged (with some exceptions, of course), upper middle class, educated, and most of all, unpretentious. The other category is much more fun to watch: those who wish to seem cultured. They tend to be young adults adhering to the “hipster trend” (the men are over groomed and the women are disheveled) and have a number of behaviors: there is the intellectual pose (involves leaning slightly back with a hand on one’s chin and staring intensely to the corner of a piece of “art”), and the catch phrase (a hurried “yeah, yeah, yeah” followed by some inane and impossible to understand comment about the power of a poka-dot). This is not an exclusively English symptom — it transcends borders and appears in almost every single modern art museum I’ve ever been to. I’m not quite sure what this says about modern art or humanity in general, but I do find a strange comfort in knowing that across nations people experience the same insecurities and behaviors.

Tags: 2010 Amy · Museums

For the majority of human civilization history has been recorded by and about men. Today we learned that portraits are just another form of history telling. In the patriarchal society that has emerged in Europe in the past few centuries, powerful men have had their likenesses recorded by painters and photographers alike. The artists, who too were white men for the most part, helped to record a history in paintings that has sent the message that in any given era, white men were the only people worthy of remembrance.

Not all of these men illustrated however, were men that were famous or powerful. One portrait that drew my attention, John Ballantyne’s The Artist’s Studio depicts a man, small and off center, carving the lions that would one day sit in London’s Trafalgar Square. It took a little researching but I finally found the picture to be painted of Sir Edwin Henry Landseer, someone whose name I was not familiar with but whose work I had seen dozens of times either on television or on the street. Even in the photo, this man is in the shadow of these monstrous lions, symbols of the aristocracy. It was interesting to finally get another perspective on the monuments all over London. All of these monuments honor great men, but behind all of them were unknown artists commissioned to sculpt or paint for little or no recognition or acclaim.

(photo from http://www.nnf10.org.uk/programme/detail/The_Artists_Studio)

Although the gallery was filled mostly with white rich men, it was refreshing to see this one painting of an almost normal guy who, like everyone else, was a subject and servant to an immutable class system.

Tags: 2010 MatthewG · Museums

September 3rd, 2010 · 1 Comment

I can agree with Jessica that most paintings in the National Portrait Gallery are of men. I didn’t expect anything else – for most of history, or at least the history that’s been recorded, men have called the shots. But I was most drawn to the portraits of Stuart queens and princesses. For one thing, they looked more real than the Tudor portraits – I can’t imagine a real person looking anything like the portraits of Elizabeth I, for example. But I can imagine Queen Anne. She looks like I could reach out and touch her. The painting of her that I found the most compelling looks like this:

http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw08095/Queen-Anne?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=queen+anne&LinkID=mp00111&role=sit&rNo=6

Queen Anne

I know a lot of this might have to do with fashion, but the Snow-White complexion, the sensual folds and materials of her gown, the emphasis on her… curves… even the placement of her hand all suggested to me a kind of softness, maternity, fertility. I can’t believe a monarch would allow herself to be presented in such vulnerability. She doesn’t look intimidating or powerful. She looks nurturing.

The caption below the portrait tells us that she was the younger sister of Mary, Princess of Orange, and that she experienced eighteen pregnancies without ever raising a child to adulthood. So this means that by the time this portrait was taken, in 1705, Anne had seen her father deposed and replaced by her sister. Her sister and brother-in-law had died. She had buried eighteen children. And then she had become one of the most powerful people in the world. I have to think you can see some of the grief she’s suffered on her face.

The portrait spoke to me because, I think, it made Anne someone real, someone for whom my heart can break. I generally don’t like the Tudor and Stuart era of British history because it seems like so many names and dates and Roman numerals and unnecessary bloodshed over highfalutin theological issues. But the women in this section of the museum brought it alive for me. Look at the resemblance between Mary of Modena, the queen of James II, and Mary of Orange, her daughter:

http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw04280/Mary-of-Modena?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=mary+of+modena&LinkID=mp02997&role=sit&rNo=0

Mary of Modena

Queen Mary II

http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw08755/Queen-Mary-II?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=queen+mary&LinkID=mp02998&role=sit&rNo=0

Different painters, different decades, and they could be twins. I wonder how Mom felt about Mary and her husband replacing James. If it weren’t for the obvious likeness in the portraits, I might never even have asked myself that question. I mean, most moms would be upset if their daughters forgot a birthday. The paintings of men in the gallery, were, for some reason, less evocative for me. I didn’t wonder how James felt about Mary’s role in the Glorious Revolution. Call me sexist, but this was my favorite part of the museum.

Tags: 2010 MaryKate · Museums

September 3rd, 2010 · 2 Comments

Beginning my tour of the National Portrait Gallery in the room of Tudor paintings, I immediately noted the types of people included in the gallery’s selection of portraits: British royalty and aristocrats. As I wove my way in and out of the various rooms and hidden side rooms, I continued to notice a broader representation of the English classes. This included notable figures of military, political, and scientific importance, as well as remarkable social reformers, explorers, poets and writers, painters and sculptors, composers and musicians, and actors. Some scenes of war and exploration–or imperialism, if you prefer to describe it as such–were additionally included in the gallery. I therefore came to the conclusion that clearly, the National Portrait Gallery really wasn’t a proper representation of all English people. There were no people of lower classes–those without distinctive historical achievements.

It wasn’t until the last galleries I explored, the contemporary portraits and portrait finalists, that I noticed another distinctive exclusion: portraits of non-white English people. I unfortunately didn’t keep an exact count of the portraits depicting any English immigrants, but they most certainly were a minority. I found this ironic, as the National Portrait Gallery cannot accurately be called “national” when countless English people are excluded from the paintings–everyday people and immigrants of other ethnic backgrounds.

The National Portrait Gallery does not share this image on its website, so I found it here.

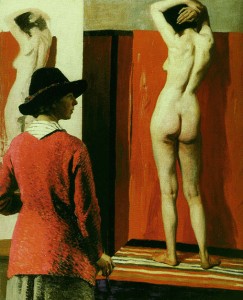

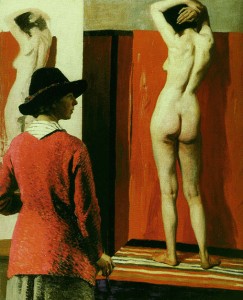

The portrait I chose in the National Portrait Gallery is “Self with Nude,” painted by Dame Laura Knight in 1913. This painting, illustrated above, is of a woman, the artist Laura Knight, painting a portrait of a nude female model. I found it striking as it was displayed in a large alcove, and its provocative nature most definitely caught my eye as it hung amongst other smaller, less distinctive portraits. Dame Laura Knight was an Official War Artist during the Great War (WWI) and recorded the famous Nuremberg Trials after WWII. In regards to this particular portrait though, it represents Knight’s prominence as a talented female painter defending the right for women to paint from a nude life model. The painting was placed in the gallery titled “We are making a New World Britain 1914-1918” where the gallery’s description stated that the Great War was an “end to an era, but it was also a catalyst for changes.”

Tags: 2010 Mary · Museums

September 3rd, 2010 · 1 Comment

Upon entering the National Portrait Gallery at its opening, I was struck by the immense size of the collection. For an art museum that had so narrow a focus, I was not expecting three full floors of work.

Beginning at the top floor, the museum took a chronological approach to the presentation of the portraits. One started going through rooms filled with portraits of the Tudors and ended observing portraits from the last decade on the bottom floor. The collection portrayed royalty, politicians, writers, musicians, artists, scientists, and other notable figures. Some of the artwork was surprisingly cynical in nature, while most were glorifications of their subjects. The term ‘national’ clearly was referring to the United Kingdom and not just England, given the presence of figures like James Joyce. Also, the collection seemed to feature figures that were mainly associated with the UK, as Handel was featured despite the fact he was born, and grew up, in Germany. A clear emphasis was placed on the rich and famous, while relatively none of the works portrayed the lower classes. Also, no one associated with the British Empire, such as Gandhi, was included.

The portrait I decided to focus on was that of Sir Francis Drake, located on the second floor. As we were not allowed to take pictures in the museum, I have provided a link here: http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw01932/Sir-Francis-Drake?search=ss&firstRun=true&sText=sir+francis+drake&LinkID=mp01357&role=sit&rNo=o

The painting of the famous navigator is not particularly flattering or, quite frankly, well painted. He stands before the observers at an odd angle, holding an oddly (aka poorly) shaped globe resting on a table for balance. Drake is dressed in a garish pink outfit, with a cape that looks too stiff too be real. His arms appear to be different sizes, and legs appear to be much larger than his torso. Looking at his face, his cheeks appear to be inflated, making him look more like a comical figure than the daring naval admiral and pirate that he was. He stands with a slight arrogant look, as if ready to take over the world (something his nation would effectively try to do in the coming decades). Looking at the portrait, it is hard to get over the poor quality of the painting. With the dismal proportions, poor color scheme, and lack of inspiration, you would almost wonder if the artist is unknown because he or she was ashamed of the work.

I picked this painting because I was so struck by its poor quality, particularly in relation to many of the other works in the National Portrait Gallery. One could almost see the work as an accidental representation of the British Empire’s colonial overreach. With the country moving so quickly to expand, one can understand the rush to make heroes out of these new explorers, evident in this portrait of Sir Francis Drake. Unfortunately, just as the Empire was built on a weak moral foundation, the picture falls victim to poor artistry. Therefore, one could read the portrait as a representation of the weaknesses of imperialism… or one can just see it as a really bad painting.

Tags: 2010 Andrew

September 3rd, 2010 · 1 Comment

The National Portrait Gallery: full of important, rich, white men (and a few others). Like most large art galleries, in my experience, those prominently featured are mainly white males. There are a few portraits of Tudor women, but they are also all white. In the exhibits featuring portraits from more recent centuries, there are increasingly more women, but I can count on both hands the number of portraits of non-whites. I feel that this is partly a reflection of what was considered acceptable subject matter for paintings in earlier centuries. It was common to paint royalty and wives or daughters of important men, but it seems that women had to be extremely important to be prominently featured in a portrait.

One of my favorite portraits was one from the Tudor era. It was, like many others, the portrait of a white male. It is, however, a self-portrait. Michael Dahl, a prominent portrait painter who moved from Sweden to England in 1682, painted his self-portrait in 1691.

I loved this portrait, mainly because I am fascinated by the mere concept of self-portraits. It is amazing to me to think about different peoples’ unique perspectives. The man that Dahl saw in his mirror when painting his self-portrait is probably not the same man that others saw when looking at him. Something else I found interesting about the portrait is the choices that Dahl made when painting it. For example, he decided not to wear a wig, the opposite of how nearly all the other men of the time were depicted. He chose to stand in his portrait and to gesture at a table which held a bust and his painting implements. He chose to paint himself from the knees up, holding an artist’s smock over his arm which covers much of his lower body. This self-portrait shows us the way Dahl wanted to be remembered. He wanted to be seen in ordinary clothes, without a wig and without makeup, with the tools of his profession nearby.

Even setting aside all of the interesting choices Dahl made, I was immediately drawn to the portrait. I thought it was absolutely beautiful. Dahl’s attention to light and shadow and his depiction of different textures astounded me. I love the way the light shines on the fabric of his right shoulder and his smock. Even the shadows and detailing on his face were more remarkable to me than in many other paintings from the same era. But then, I have to wonder just how accurate the self-portrait really is. Did Dahl omit less favorable features because of personal vanity or did he paint himself exactly as others see him? Was he more or less critical of himself than others were of him? I wish I could answer these questions, but I can only make assumptions based on my limited knowledge of psychology.

Tags: 2010 Jessica

September 2nd, 2010 · 8 Comments

Have you ever wondered what the world would be like if we didn’t make divisions amongst each other based on race, class, culture, or religion? I have. I have wondered would it ever be possible to achieve this? Growing up in South-Central Los Angeles taught me two things; stick to those like you, and every man for him/herself. These “teachings” however always felt wrong, and they were. My parents ensured that within our household each member is open to different races, class, culture, and religion through the art of inquiry and respect. But as much as my parents taught me this and as much as I practiced it I have never truly found it reciprocated. That was until August 30, 2010, location-the Notting Hill Carnival.

I had to travel 16 hours away from home, South -Central Los Angeles to find what I believed to be impossible. The Notting Hill Carnival began in 1964, as a way to celebrate the cultures and traditions of the Afro-Carribbean communities that reside in England. Over time it has become the largest street festival in all of Europe. (For further information go to http://www.thenottinghillcarnival.com/history.html) This festival, which celebrates, cultures and traditions of people not native to England itself could only reach its magnitude through support and participation of outsiders. That is precisely what I witnessed and felt this last Monday, August 30. As previously trained by experience, I expected the Carnival to be filled with Afro-Caribbean people and only a trickle of White-British people. To my astonishment the Carnival contained thousands upon thousands of White-British people who were not just there to observe this beautiful festivity but were actively participating through their wear, dancing, and eating of foreign food. It was bliss. It somehow gave me back that sense of hope that I had lost a while back; the hope that we as a people really can accept one another and beyond that celebrate one another’s differences.

Afro-Caribbean cultures were completely new to me. California, really only has cultures from Central and South America, and much of Eastern Asia. Therefore, before last Monday, I had never seen nor tasted Jamaican food. Luckily, I had Melissa Gurdon with me, a Jamaican-American , she quickly gave me the run through of Jamaican cuisine. After a plate of Jerk Chicken and Sweet Corn, I was in heaven. After seven hours of being in Notting Hill, Melissa and I, finally decided to hit the road and return to our home in Bloomsbury with a full stomach and a happy heart; hoping to return in one years time.

Tags: 2010 Jamie

September 2nd, 2010 · 4 Comments

In England, I have discovered beer to be an appropriate beverage for any time, place, or person. It can be a drink of the everyman and a drink of the aristocrat, a refreshing drink for the conservative manual worker or the Avant-garde intellectual. In my first week in London, I have had beer in so many different contexts that I am now convinced of this fact.

At the Notting Hill Carnival, London’s yearly Afro-Caribbean festival, Red Stripe (a popular Jamaican beer) was the name of the game. Jamaica, similar to former British colonies across the Caribbean, contributed a lot to British culture, including its own style of Britain’s favorite beverage. It seems that where the British once had power, breweries became an essential craft. In this way, the exportation of beer and the making of international beer culture appears to have colonialism to thank.

Colonialism wasn’t that only “ism” that beer has exposed me to this week. The British Museum, one of the world’s most important cultural institutions, has been a place of study for intellectuals since its creation at the end of the 18th century. When these intellectuals were not studying however, I have read that many of them would go across the street from the museum to the Museum Tavern for a pint. After a few intellectually stimulating hours in the museum, we made our way across the street to the tavern. The décor was similar to all other pubs we had visited but this one seemed a bit more authentically 19th century. This feeling was only enhanced by a pint of very delicious ale called “Old Peculiar.” What really struck me about the drinking in this particular pub was knowing that somewhere in that very room Lenin and Trotsky had sat and contemplated ways to liberate the peasants of Russia, or that Marx had sat with a pint after the long days spent writing Das Kapital across the street. Just as beer played a part in British imperialism, so too was beer present in the forefront of intellectualism in Britain.

Classism is also a British cultural topic demonstrated by beer. As iterated by Kate Fox in her book, Watching the English, your choice of beer/beverage can say a lot about a person’s social class. The bartenders and the English people in the pub expect certain people to buy certain drinks and my choice of beer could break unwritten social rules and earn me a liberal amount of strange looks. I have seen this first hand when ordering a half pint of cider (to protect my standing in British society, I must add that this was done for a lady).

Imperialism, Intellectualism, and Classism. All three of these British “isms” are cultural concepts that are literally seeped in beer.

Tags: 2010 MatthewG · Pubs · Uncategorized