Tag Archives: Sustainability

Unintended Consequences of Nuclear Energy

The development and implementation of nuclear energy programs has proved to be a double edged sword. Although harvesting the potential energy of nuclear fissions original intention served to gain advantage in war, scientists shifted their aims to utilize nuclear power as an energy source. Nuclear energy is not only more efficient than fossil fuels, but also proves much less harm to the atmosphere. Governments, unaware of the potential consequences of running large nuclear power plants (NPPs), installed them primarily in Russia, the United States, France, Germany, and Japan. The immediate consequences of NPPs remained practically non-existent—experts knew radiation exposure could be a fatal and is why nuclear arms were tested in remote, uninhabited areas. Containment and control were primary safety concerns during the establishment of NPPs, but scientists and the public failed to predict the potential consequences of nuclear energy. Due to nuclear fuel emissions, inadequate operations, and devastating nuclear disasters, the unintended ramifications of nuclear energy development manifest themselves in the form of radioactive wastes, contaminating gasses and emissions, and harmful environmental effects both on fauna, plant life, and humans.[1] Another issue scientist took into calculation but failed to control proved to be the long-term effects of fallout on the environment and humans resulting from nuclear weapons testing. Although isolated locations were chosen to execute tests for observatory purposes, nearby humans developed side effects from the draft of nuclear fallout. These include growths, irritation, ulcers, cancer and other health risks.[2]

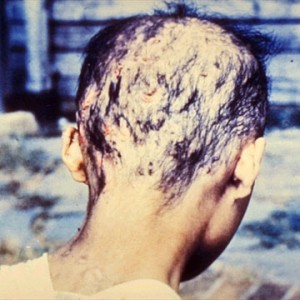

The largest concern for nuclear weapons testing and nuclear meltdowns remains the delayed effects of fallout, or radioactive products that have settled to the ground.[3] BRAVO, a thermonuclear bomb tested above Bikini Atoll in 1954, unpredictably gave the children in the proximate Marshall Islands thyroid nodules, lesions, and lasting medial problems. The radius of destructing was thirty times what scientists estimated, and an unpredicted shift in wind patterns carried fallout over two hundred kilometers away. The skin of fisherman over eighty miles away was scorched to blistering, as white as enveloped them and contaminated their catch.[4]

Burns are a short-term symptom, coupled with blast injuries and radiation illness. Lasting, unintended injuries plague the victims of nuclear weapons as well. Ionization radiation damages chromosomes by radioactive particles breaking up molecules and creating free radicals, which “damage DNA and disrupt cellular chemistry in other ways – producing immediate effects on active metabolic and replication processes, and long-term effects by latent damage to the genetic structure.”[5] Victims of radioactive fallout are also extremely susceptible to hair loss, due to the effects from disturbance in lymphatic tissues, blood, and the immune system, leading to continual cell division.

Although damage to chromosomes can heal over time, side effects can manifest themselves many years later, and it is quite possible to develop cancer due to cell division.

Contrary to popular belief, the genetic disturbances nuclear radiation has on human DNA rarely causes mutations due to high rates of genetic variability and uncertainty. Another reason is because high levels of exposure usually damage reproductive tissues to the point of sterilization, which prevents the transmission of genetic defects.[6] These fallout effects are not exclusive to nuclear weapons testing and use; they are also a product of large-scale nuclear accidents.

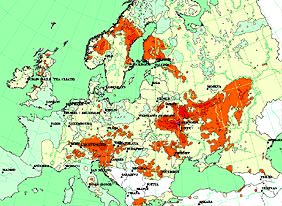

In 1989, reactor four of the infamous Chernobyl nuclear power plant experienced a melt down due to improper management. The Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe in 1986 introduced extremely large amounts of radioactive waste into the atmosphere, which continue to have unpredicted consequences throughout the Soviet Union and Western Europe.

Effects on agriculture, the environment, and health risks are three of the major unintended consequences that are a byproduct of nuclear radiation fallout from large-scale nuclear accidents. The disaster destroyed forests, contaminated water supplies and had devastating effects on wildlife. Britain experienced effects from fallout a week after the disaster, resulting in a dip in the economy due to radiation in the livestock, crops, and food. [7]

The consumption of contaminated meats and food inevitably leads to side effects, and the agricultural markets of Great Britain fell as farmers, who were hit hard by the fallout as their livestock ate plant life with radiation and became contaminated. Groundwater, and especially plant and animal life all suffered detrimentally as a result of the nuclear meltdown. Although the effects on the drinking water were seen to be generally non-threatening in the immediate aftermath due to the insolubility of the radioactive particles in water, the accumulation of radiation in fish in the nearby areas made them too dangerous to eat. The famous “Red Forest” is a direct product of the Chernobyl meltdown, a four-kilometer area of woods that died after the incident.

Due to caesium-137 particles, which were absorbed into the environment, scientists are estimating it will take roughly one hundred years to for these woods to recover.[8]The unintended human death toll due to cancer as a result of fallout rests at higher rates than most are aware of.

The Internal Agency for Research on Cancer released its estimation that 16,000 cancer deaths by the year 2065 are a result of the Chernobyl accident in the Journal of Cancer in 2006.[9] These estimations, however, wane quite significantly. The actual effects that Chernobyl fallout has had on the population is still a debated topic, with sources conflicting drastically. The most conservative estimates claim only four thousand cancer related deaths as a result of the Chernobyl meltdown, where as the higher estimates range up to 200,000. In contrast to The World Health Organization estimated that there were roughly four thousand cancer related deaths as a result of the accident, the Chernobyl Forum estimated that throughout Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, radiation poisoning could have killed between 10,000-200,000 people.[10] The plant and wildlife in Europe was also widely affected by this disaster as well.

The animals closer to the Chernobyl accident experience many physical health issues. Many horses in the nearby area died because their thyroid glands were destroyed by radiation. Thyroid damage and thyroid cancer is a common side effect of exposure to higher doses of radiation, and inhibited the physical maturation of cattle in the nearby area as well. In Germany, 2010, one in every approximately 450 boars hunted were too radioactive to eat. In Norway, 2009, a total of 18,000 livestock had to be fed special, clean, radioactive free food until the radioactive contaminants had been purified from their systems before consumption. [11] One way of preventing future radioactive issues is by properly containing nuclear waste, making nuclear waste storage extremely important in the long term due to the long lasting nature of the radioactive particles.

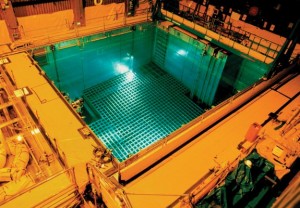

Radioactive waste is an all-encompassing term, as it refers to “the leftovers from the use of nuclear materials for the production of electricity, diagnosis and treatment of disease, and other purposes.”[12] A common strategy is to reduce the volume of waste through the methods of compaction and incineration. The two different types of waste, high and low level, are handled differently. Low-level waste products such as radioactively contaminated clothes or handled items. High-level waste is primarily nuclear reactor fuel and is usually kept at nuclear power plants due to their lack of proper disposal.

Low-level wastes are placed in radioactive waste containers and are often stored at the production zone or a NPP. In order to avoid further radioactive waste leakage and prevent future environmental damage, more methods need to be developed to store nuclear waste.[13]

The consequences of nuclear energy programs have been quite significant in terms of environmental and human affliction. Although scientists intended for the immediate short-term effects of nuclear weapons to take place, and even the longer ones—they did not accurately predict the impact it would leave on the environment and people resulting from theoretically harmless tests. The NPP programs were intended to be entirely harmless, but resulted in most likely tens of thousands of deaths worldwide, although that number is still being determined. Radiation leads to the destruction of water sources, environments, and society on a smaller scale. Humans have been developing cancer from the fallout, contributing to excess deaths potential, low-grade mutations and infertility, especially in zones proximate to the meltdowns. Storage of radioactive waste is still challenging scientists and the government. Its potency lasts as long as the contaminated particle remains radioactive, which is usually hundreds of years or more. It remains imperative to master the transportation and storage of nuclear waste to make our nuclear programs more sustainable. Had scientists been aware of these potential ramifications, they would have approached the development and control of the nuclear industry with more caution.

[1] Wikipedia. “Environmental Impact of Nuclear Power” Last modified November 26, 2013

[2] Sublette, Carey. “Section 5.0 Effects of Nuclear Explosions”. Nuclear Weapon Archive. Last modified May 15, 1997.

[3] Sublette, Carey. “Section 5.0 Effects of Nuclear Explosions”. Nuclear Weapon Archive. Last modified May 15, 1997.

[4] Cavanaugh, Jamie, Suzie Genyk, and Emma Uman. “Environmental Impacts of Nuclear Proliferation.” University of Michigan.

[5] Sublette, Carey. “Section 5.0 Effects of Nuclear Explosions”. Nuclear Weapon Archive. Last modified May 15, 1997.

[6] Nuclear Weapons Archive.org

[7] Chris C. Park. Chernobyl: The Long Shadow (London, New York: Routledge, 97-99).

[8] Wikipedia. “Environmental Impact of Nuclear Power.” Last modified October 16, 2013.

[9] Wikipedia. “Environmental Impact of Nuclear Power.” Last modified October 16, 2013.

[10] Wikipedia. “Chernobyl Disaster.” Last modified December 12, 2013.

[11] Wikipedia. “Environmental Impact of Nuclear Power.” Last modified October 16, 2013.

[12] U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. “Radioactive Waste.” Last modified February 21, 2013.

[13] U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. “Radioactive Waste.” Last modified February 21, 2013.

The Composers’ Union and Sustainability

Elephantine marches and songs of the Motherland…these are some thoughts that might come to mind when thinking about music in Soviet Russia. Although there is some truth to these popular assumptions, there is much more detail about music under Stalinist Soviet Russia. Specifically, there is the detail of Stalin’s creations of creative unions. These unions had various sects for artists such as architects, cinematographers, and writers, just to name a few. This paper will focus on the union for composers. The union for composers was a time of chaos with the shift of power with the renaming of these unions at various times, a period of control, as exemplified in Dmitrii Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, and an era of great artistic achievement for the State, as seen in the creation of the new national anthem. Additionally, sustainability played a part in these unions. Sustainability is the maintaining of social, economic, and environmental aspects. When all three of these are coevolving and present, sustainability is met. How does sustainability fit in the Union of Composers? What is the history of this union?

Organized musical structures in Russia can be traced back to the Russian Musical Society, which formed in 1859. In the 1920s, two associations of Russian music dominated: the Association for Contemporary Music and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians. The Central Committee passed a resolution in April of 1932, eliminating these two associations. The resolution called for the creation of a new artistic organization. This is when the creative unions came into being. The musical sect of these artistic unions was called the Composers’ Union. The resolution eliminated all professional artistic unions except the artistic unions created by the State. However, when these unions had just begun, the Soviet government showed little leadership in the musical details of the union[i]. So, the larger cities such as Moscow and Leningrad began forming their own municipal composers’ unions. These municipal unions were highly efficient, having different departments to oversee various tasks. As these unions gained more publicity, the Soviet government formed a new, powerful committee. The Committee on Artistic Affairs, formed in January 1936, wanted to revitalize the arts in Soviet Russian. The rise of this new governmental committee eventually created a powerful, united, all-USSR composers’ union.

Disappearing Culture: Indigenous Tribes in the Noril’sk Region of Siberia

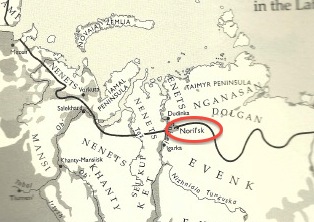

Early in the Soviet era, the government paid little attention to the indigenous tribes of Siberia and did not take into account whether their policies for modernization would have a negative effect on the native peoples. Collectivization and the push for industrialization directly affected the tribes’ economic activity, traditional lifestyle, and the environment in which they lived. Industrialization took place across the Soviet Union, however I have chosen to focus on the city of Noril’sk, located in Krasnoyarsk Krai in northern Siberia, between the Yenisei River and the Taimyr Peninsula. Four main indigenous groups converge in the area of Noril’sk; these groups are the Dolgan, the Nenets, the Nganasan, and the Evenk people. As a result of Soviet collectivization and industrialization policies of the mid-twentieth century, the traditional culture of these indigenous groups altered or faded considerably.

Here is a map showing the geographical location of Noril’sk:

Source: www.thenytimes.com

A key component of analyzing these policies and their effects on these four tribes is to consider the sustainability of these policies with regards to both the environment and the tribes’ traditional ways of life. I would like to clarify that I am defining sustainability as “long-term cultural, economic and environmental health and vitality….together with the importance of linking our social, financial and environmental well-being.” This definition comes from the organization Sustainable Seattle.[1] I argue that Soviet policy towards the indigenous tribes of Siberia in the twentieth century did not promote long-term cultural, economic or environmental vitality, and were therefore unsustainable and unsupportive for the indigenous clans of the region.

Below is a map showing the location of Evenk, Dolgan, Nenet and Nganasan territory relative to Noril’sk and to each other:

The map above shows that Noril’sk serves as a sort of epicenter for these four groups: the Dolgans, Nenets, Nganasans, and Evenks. To learn more about a specific group please click the hyperlinks for further reading. Not only are these four clans close in proximity, but also—like many Siberian tribes—each clan has historically depended on reindeer hunting or herding for their economic livelihood. This does not mean these groups are all the same; they descend from different Eurasian or East Asian ethnic groups and each speak their own native language, among other differences. That being said, each clan experienced similar difficulties adjusting their traditional lifestyles during collectivization and industrialization. There are many ways in which the Soviet Union altered the lives of tribal people in Siberia; collectivization and industrialization are simply the two policies I have chosen to analyze.

Shrinkage of the Aral Sea: Detrimental Effects

Elizabeth Lowman

When the Bolsheviks came to power in 1917, their rule was marked by the desire to control everything, including nature. What resulted is what demographers Murray Feshbach and Alfred Friendly referred to as “a sixty-year pattern of ecocide by design.”[1] Ecocide is the practice of destroying an environment’s ecosystems. Alternatively, sustainability is the practice of taking no more from the environment than can later be replaced. The Soviet Union abandoned the idea of giving back to the earth by taking as much as they could to make a profit.

Over-irrigation from the Aral Sea was one of the worst instances of Soviet environmental control. During the rule of Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union embarked on the “Virgin Lands Campaign,” which plowed untamed lands to grow food for the Soviet Union. The Soviets realized that the Central Asian nations of Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan could be used for growing cotton. Officials called cotton “white gold” and were pleased when the USSR became the second largest cotton producer in the world by the 1980s.[2]

Located between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan lays the Aral Sea, which was the fourth largest sea in the early 1960s.[3] Two rivers act as tributaries, feeding the sea with water that the Soviet government then used to irrigate cotton. However, since irrigation systems were not designed properly, less and less water began to reach the sea.[4] The result was the Aral Sea shrinking by 44 percent.[5] Fertilizers and pesticides the Soviets fed used on the cotton also contributed to the sea’s shrinkage.

The Soviet Union’s irresponsible cotton growing campaign harmed Central Asia on multiple levels. The shrinkage of the sea destabilized the environment and ecosystem. Public health in Central Asia still is deeply threatened by multiple environmental and social factors introduced by the cotton campaign. Russia’s exploitation of Central Asia caused the Central Asians to believe they were treated as second-class Soviet citizens, leading to political unrest in the region.

The shrinkage of the Aral Sea had devastating consequences for the surrounding environment. These consequences included the destruction of the sea itself, land and water pollution, and increased wind erosion.

Poor Soviet irrigation methods took their toll on the sea, draining it to one third of its former volume. In addition to that, the chemicals, pesticides, and fertilizers fed to the cotton by the Soviets contaminated the remaining water as well as the miles of sand serving as a reminder of the Aral Sea’s former breadth.[6]

The water pollution introduced by these chemicals had a wide range of affects. The salinity of the water is now equivalent to that of an open ocean,[7] six times the limit set forth by the World Health Organization. This affects the quality of drinking water available to those living around the sea. Scientists still are uncertain whether foul tasting water has any detrimental health effects that extremely high salinity can potentially cause,[8] which will be addressed later.

High salinity is not the only problem with the water. Sixty-five percent of the water in Karkalpakstan, a republic in Uzbekistan, does not meet health regulations for pollution.[9] The sea also has high levels of lead and cadmium.[10] While the pollution is most likely harmful to humans, it has definitely proven harmful to fish. All twenty of the important fish species of the Aral Sea have died.[11] Fish kills signify the potential danger of the water but also eliminated a source of food and income to the people inhabiting the area around the sea.

Another environmental problem present in this region, wind erosion, spreads 43 million metric tons of the contaminated sand and silt from around the Aral Sea to the surrounding lands, inhibiting plant growth.[12] The wind erosion has worsened since the 1970s, when the Soviet government forced Central Asian peasants to cut down trees to make room for cotton.[13] With nothing to hold down the soil, wind erosion continues to take its toll on the land.

Intense dust and salt storms are another consequence of wind erosion. In the 1980s, between 90 and 140 million tons of salty sand were carried as far as Belorussia and Afghanistan annually.[14] As will be discussed later, the frequent storms may be causing increasing cases of respiratory problems in the population.[15]

Between poor irrigation, polluting the land and water, and deforestation, the Soviets caused extreme damage to the environment in the pursuit of cotton.

These environmental effects closely tie in with the adverse health affects seen in the population. These health effects include disease outbreaks, contaminated breast milk, and respiratory problems. In the 1980s, many of these problems could be directly attributed to the destruction of Aral Sea, but today, data is inconclusive as to the extent of damage being done to people’s health.

In the past, the drinking water for those that live around the Aral Sea was unfit for human consumption. In the 1980s, “Turkmenistan’s health minister described the Turkmen canal, a major source of drinking water, as an open sewer after finding impermissibly high bacteria counts in 60 to 98 percent of all water samples taken from it.”[16] In addition to pesticides, fertilizer runoff introduced bacteria into the water. Diseases such as hepatitis, typhoid, dysentery, and cancer plagued the population. According to some counts, “hepatitis…afflicted seven out of every ten inhabitants.”[17] These diseases were either caused by waterborne bacteria and viruses, or by heavy metal deposits found in the water.

As discussed earlier, scientists today are unsure if the drinking water is still dangerous to humans, although they find it quite possible. However, scientists do know that Central Asia has an extremely high infant mortality rate, with infants dying of upper respiratory infections, diarrhea, tuberculosis, and malnutrition. Contaminated water is a likely suspect for outbreaks of diarrhea. The World Health Organization also expressed concern that the Aral Sea region lacks a steady and safe water supply, which is unsafe for children.[18]

High infant mortality could also be a result of contaminated breast milk in mothers. Scientists found the milk to be contaminated with PCBs and other pesticides the Soviets used on the land after a study they performed in Kazakhstan. Scientists hypothesize women come into contact with these chemicals by eating fish from areas of high water pollution, as well as through agricultural products that are grown with pesticides.[19] However, the amount of PCBs and other pesticides detected were still less than amounts found in industrialized nations, with the exception of in Atyrau, a city in Kazakhstan, where the amount of pesticides were found to be the same as in industrialized nations.[20] Currently, the toxicity of the breast milk is inconclusive, but in the late 1980s, doctors warned Turkmen mothers against breast-feeding because of toxic milk.[21] Today, many Central Asian women are reluctant to breast-feed their infants.

As previously mentioned, the frequent dust storms seen in Central Asia can have ill effects on people’s health. The Aral Sea Dust and Respiratory Disease Project sought to find a correlation between the environment and public health. Respiratory diseases are responsible for many illnesses and deaths in Central Asia. In fact “fifty percent of all illnesses in children are respiratory.”[22] From 2000-2001, researchers discovered that dust inhalation in Central Asia was dramatically beyond the guidelines of the Environmental Protection Agency in the United States. Overall, the results were inconclusive, as more respiratory infections occurred farther from the Aral Sea, possibly caused by other sources or by the ability of dust to travel. Researchers hypothesized that not all dust was from the Aral Sea, but most of the dust in the late summer dust storms was likely from this region.[23]

The link between environmental damage and public health disasters was strongly established in the 1980s as chemicals, pesticides, and bacteria poisoned many Central Asians. While this link is not as clear today, many researchers believe Central Asians are still suffering because of the environment.

Because of the damage being done to their land and their health, Central Asians began to resent Russia, causing political issues. Moscow’s complete disregard for the region’s plight was “a measure of the second class status” of the predominately Muslim Central Asian states.[24] Because Central Asia is religiously and ethnically different from Eastern Europe, the Soviet government cared little about the issues Central Asia faced. As well as destroying the land for profit, the Soviet government refused to give Central Asians adequate medical care. “In the four [Central Asian] republics together in 1987 there were, on average, fewer than 14 pediatricians for every 10,000 children,” a fraction of what was seen in the rest of the Soviet Union.[25]

At first, Central Asians cooperated, but they soon began to defend their rights as Soviets. Spokespeople accused Moscow of genocide. Nationalists demanded Moscow redirect Siberian rivers to Central Asia to provide clean drinking water. Uzbek nationalist groups, originally concerned with promoting the Uzbek language, expanded their campaigns to include environmental reforms. Journalists wrote of malnourished children. In an attempt to pacify what they perceived as a potential revolt, the government would make promises and send aid. However, the promises were not kept and the aid was unsubstantial. Although the republics of Central Asia declared their independence in 1991, relations with Russia still remain icy, in part due to the Virgin Lands Campaign.[26]

Some progress has been made in recent years to rehabilitate the Aral Sea. In 1999, the World Bank launched a project in which it built a 13-kilometer dike in one of the Aral Sea’s tributaries to raise sea level and decrease salinity. The project went even better than expected, with the tributary reaching the intended level within only seven months, as well as the its capacity doubling to 700 cubic meters per second. The next goal, set forth by Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev, is to raise the sea level of the northern sea four to six more meters.[27] For the first time in decades, the world is feeling more optimistic about the plight of the Aral Sea.

The Soviet Union’s fierce desire to control nature with no regard to sustainability destroyed the environment, the health of Soviet citizens, and Russian-Central Asian relations. Though optimism about the region is growing, it is unlikely the Aral Sea will ever return to its former glory. The Soviet Union ruthlessly exploited the land for profit, and decades later; Central Asians are still paying the price.

Notes

1.Murray Feshbach and Alfred Friendly, Jr. Ecocide in the USSR: Health and Nature under Siege (New York: Basic Books, 1992), 75.

2. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 74.

3. Kerstin Lindahl Kiessling. “Conference on the Aral Sea: Women, Children, Health and Environment,” Ambio 27, no. 7 (1998): 560.

4. Ian Small, J. van der Meer and R.E.G. Upshur. “Acting on Environmental Health Disaster: The Case of the Aral Sea,” Environmental Health Perspectives 109, no. 6 (2001): 547.

5. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 74.

6. Kiessling “Conference on the Aral Sea, “ 560.

7. Kiessling “Conference on the Aral Sea,” 560.

8. Small, et al., “Acting on Environmental Health Disaster,” 548.

9. Small, et al., “Acting on Environmental Health Disaster,” 548.

10. Giles F.S. Wiggs, Sarah L. O’hara, Johannah Wegerdt, Joost Van Der Meer, Ian Small and Richard Hubbard. “The Dynamics and Characteristics of Aeolian Dust in Dryland Central Asia: Possible Impacts on Human Exposure and Respiratory Health in the Aral Sea Basin,” The Geographical Journal 169, no. 2 (2003): 143.

11. Small, et al., “Acting on Environmental Health Disaster,” 548.

12. Kiessling, “Conference on the Aral Sea,” 560.

13. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 77.

14. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 75.

15. Wiggs, et al., “The Dynamics and Characteristics of Aeolian Dust,” 143.

16. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 76-77.

17. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 77.

18. Kiessling, “Conference on the Aral Sea,” 563.

19. Kim Hooper, Myrto X. Petreas, Jianwen She, Pat Visita, Jennifer Winkler, Michael McKinney, Mandy Mok, Fred Sy, Jarnail Garcha, Modan Gill, Robert D. Stephens, Gulnara Semenova, Turgeledy Sharmanov and Tamara Chuvakova. “Analysis of Breast Milk to Assess Exposure to Chlorinated Contaminants in Kazakhstan: PCBs and Organochlorine Pesticides in Southern Kazakhstan,” Environmental Health Perspectives 105, no. 11 (1997): 1250.

20. Hooper, et al., “Analysis of Breast Milk,” 1254.

21. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 73.

22. Wiggs, et al., “The Dynamics and Characteristics of Aeolian Dust,” 143.

23. Wiggs, et al., “The Dynamics and Characteristics of Aeolian Dust,” 152-155.

24. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 75.

25. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 81.

26. Feshbach and Friendly, Ecocide in the USSR, 83-88.

27. Christopher Pala, “Once a Terminal Case, the North Aral Sea Shows New Signs of Life,” Science 312, no. 6 (2001): 183.

Works Cited:

Aral Sea dust storm from space (NASA)

Aral Sea dust storm from space (NASA)

Ship on the remains of the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan (Wikipedia Commons)

Ship on the remains of the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan (Wikipedia Commons)

Moving map showing the shrinkage of the Aral Sea (Wikipedia Commons)

Moving map showing the shrinkage of the Aral Sea (Wikipedia Commons)

Video:

Development of Nuclear Waste and Sustainability in Russia

From the radiation of its food to the radiation of its rivers, Russia has built itself into a competitive nuclear power through a tumultuous history of trial and error.[1] Much of the initial funding for Soviet nuclear energy came in an effort to match the United States’ atomic project. But, after developing “the bomb”, nuclear resources in the USSR were applied to a number of areas. These often gave poor results. From such failures, modern Russia has striven to provide a nuclear industry that is safe, clean, and sustainable. In fact, the head of Rosatom’s used fuel management has set a goal of 100% efficiency in the company’s fuel cycle; where all spent fuel is reprocessed into the system — no waste.[4] To understand these, at first, outlandish expectations, we should consider the damages and adaptations that the industry has incurred since its inception in the 1940s.

In the earliest days of the Soviet nuclear industry, one of the most practiced efforts was the irradiation of food. This gave food stuffs a much longer shelf life and they exhibited fewer incidents of contamination due to bacteria or spoiling. But, this also exposed many citizens to harmful levels of radiation after sustained consumption.

In an effort to appease the growing “green movements” in the Soviet Union, Stalin once pursued an aggressive hydro-electric policy. To map the currents in possible rivers, the Soviets had opted to use radioactive isotopes instead of foreign nutrients. These isotopes gave far more accurate readings than the nutrients which would dissolve more quickly in the water. Unfortunately, these tests also irradiated the sites on which they were conducted.

Fantastic Diseases and Where to Find Them

The easiest way to find a fantastic disease in Russia is to do a search of its prisons. Through unsustainable practices such as the failure to continue treatment of highly communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis, once an inmate has been released from prison, tuberculosis has spread in places where it can be easily treated.[1] In order for health in Russian prisons to improve, measures must be taken to ameliorate the inadequate living conditions that spread communicable diseases.[2] The World Health Organization (WHO) created the Health in Prisons Programme (HIPP) in 1995 to fix the major issues of prison healthcare in Europe and create a more sustainable prison health care system. [3] Hopefully, with programs like these in place, Russia will develop a solution to the health care issues that have plagued its society for decades. Continue reading

Unintended Consequences of Nuclear Development

During my research for informational websites relevant to my topic, I came across a lot of overlapping information about the effects the nuclear industry has had on our environment. The two most valuable web sources are wikipedia, and the information from the nuclear weapons archive. Both websites have the most expansive but simultaneously in depth information on my topic. A few of the websites cover both high and low level effects on the environment, and others discuss the effects on humans and cancer on the subatomic level.

The websites span from topic of nuclear weapons testing to information justifying the banning of nuclear testing through the passing of treaties. My sources are all very recent with the exception of the source belonging to the nuclear weapons archive, which dates back to 1997. I did not use the Evernote application in my research, therefore I have no feedback to how it positively or negatively effected my progress. This is the first time I have ever used the Dropbox program. I found it to be very a straightforward and convenient way to share documents. The scope of my research hasn’t changed as a result of my new sources, as they all had specific relevance to my original topic. I am going to proceed by collaborating with Barret to make sure our research aligns to stay relevant, and will continue to focus on the unintended nuclear effects that testing and reactors have had on the environment and humans.

Shrinkage of the Aral Sea

My final report is about the shrinkage of the Aral Sea. I will be concentrating on four points. The first point is the cause of the shrinkage of the Aral Sea. I will discuss how the Soviets in Moscow wanted to harvest great quantities of cotton from Central Asia. In order to do this, they used the Aral Sea for irrigation to such an extent that the sea’s area shrank by 44%. This caused many health and environmental consequences for Central Asia.

The environmental consequences that I will discuss include flooding due to poor drainage systems, the poisoning of water and soil by pesticides used to grow the cotton, dust storms, and deforestation. The health consequences I plan on discussing include starvation, infant mortality, contaminated breast milk, and the prevalence of water-born illnesses such as typhoid, hepatitis, and dysentery.

The final point of discussion will be the possibility of rebuilding the Aral Sea, along with the successes that have occurred since the collapse of the USSR.

I will need to continue doing more research for my report. I am anticipating that the most challenging part of the project for me will not be the material, but the technological aspect of creating a website. This is the part that I will need to dedicate the most time to, as I have never done anything like it before.

So far, I have learned the importance of examining sources on multiple levels. First, getting articles from reliable databases, such as JSTOR, helps. Also, the fact that some of the authors I cited were cited in other scholarly articles gives more credibility to the authors. It is also important to have articles written by professionals, such as historians and scientists, and not university students or bloggers. The author’s credentials separate a scholarly article from an unscholarly article.

I also had to make sure, especially in the scientific texts, that I understood the point of the article. If an article is too difficult to comprehend, then it is pointless to cite it.

As for my critique of Evernote, my only issue was that it changed the format of the bibliography. I found it easier to use Microsoft Word.

Here is my annotated bibliography:

Nuclear Waste and Sustainability in the Russian Nuclear Industry

Of the scholarly websites and books that I am using for this project I have found a number of similarities. Many of these sources are a form of anthology, where books have chapters the web sites have pages. But, a very distinct feature of the web site is its growth and development. Where a book would have to be republished, or have additional volumes, a web site allows for scholars to access and revise a number of times with relative ease. Additionally, on some internet outlets, the sites allow for commenting on articles or provide links to response pieces. This illustrates an evolving dialogue in the field that a book is, by nature, unable to provide.

In looking for the number of multimedia sources that this project has prescribed I have developed a number of skills that have already begun to help me in other areas of my research. I have found that much of a topic’s philosophy and history is easiest found in reliable scholarly texts, but having websites or scholarly blogs provide more contemporary and evolving views.

As for my review of Evernote, I must say that it has been difficult to preserve the bibliographies’ citation format while using the program. I have found it useful for storing snippets of information for personal use, as I can access it across platforms. I did not find myself using Evernote to discover other information gathered by users that might pertain to my research, but I can see such a service being useful. Ultimately, the service falls short of our primary need for it — class sourcing — when our primarily shared document, the bibliography, is so negatively affected.

I have begun plotting a timeline. By going through each source and plotting relevant data on a time scale, I can identify patterns of change. Already I have found correlations between the evolution of reactor designs and the “Green Movement” starting in the 1980, which was unexpected. Many of my preconceptions of Soviet nuclear policy have been changed by the research I’ve done and I feel far more open to interpreting the information than using it to support what I believed to be true.

Here’s a link to my bibliography: