While viewing pictures of the gulags on gulaghistory.org, I was reminded of the pictures of Auschwicz I had seen in high school during our holocaust unit. The starvation, disease, and forced labor I read about on the site, as well as in the book A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich seemed reminiscent of the Nazi concentration camps.

These facts made me wonder why in American culture Joseph Stalin’s crimes often seem to be minimized. (Not that I believe Hitler’s crimes are exaggerated at all.) According to the Jewish Virtual Library, 11 million people were killed in the Holocaust. According to the International Business Times, Stalin’s kill count is estimated to be 20 million. *Both counts vary according to different sources.

I will not try to determine “who is worse.” I am merely examining why Hitler seems so much more evil to Americans than Stalin does, while, at first glance, they committed similar crimes.

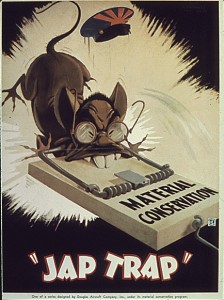

I think the reason America remembers Hitler more than Stalin is because 1) Hitler was concerned with the extermination of certain races 2) Hitler killed using more sadistic methods 3) Stalin’s crimes were internalized to his country and 4) Stalin had been an American ally.

While Hitler was probably “more racist” as his entire philosophy was based around race, Stalin wasn’t exactly Martin Luther King. He sent various nationalities to the gulags because he perceived them as a threat. These nationalities included Ukrainians, Germans, and yes, Jews. So Stalin was also anti-Semitic. Though he was arguably less so than Hitler, (he didn’t want to actually exterminate them), does it really matter who is more or less anti-Semitic? Both of them killed people simply for being Jewish. Which we can all agree is incredibly wrong.

Yes, Hitler was definitely more sadistic than Stalin. While Stalin killed people who he felt threatened by, Hitler almost seemed to take joy in the pure act of sadistic killing. My guess is that this is what truly sets the two apart in the minds of most Americans. Stalin joins the ranks of Genghis Khan and the ancient Roman emperors- killing because they believed they had to in order to remain in power. Hitler’s more of a Jeffrey Dahmer figure with unlimited power.

Hitler also attempted to take over Europe: Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, the Netherlands, France and an alliance with Italy, and an attempt on Russia. When he would take over a country, he would send the local Jewish, Romani, handicapped, etc. populations to concentration camps (except in the case of Poland, where he basically sent anyone he could). Stalin stuck to the Soviet Union. While it was the largest country in the world at the time, it was Stalin’s, so he could more or less do as he pleased.

Finally, during World War II, the United States sided with the Soviet Union, and Stalin. First of all, Soviet troops fought valiantly against Hitler, following the “enemy of my enemy is my friend” rule. Also, as we did ally ourselves with Stalin, we may have trouble admitting we sided with someone who was basically as evil as the one we were fighting against.

Stalin is perceived as less racist and less sadistic than Hitler. He stuck to his own territory and was even an American ally for a little while. Whether deserved or not, these reasons make Stalin the “lesser of two evils” for many Americans.

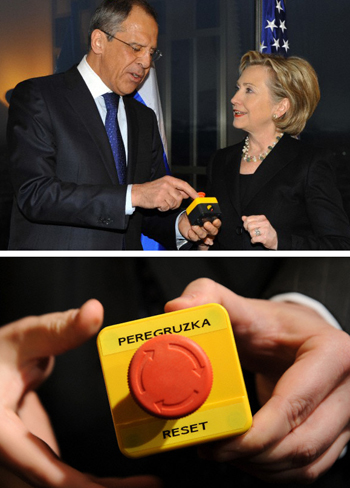

Perestroika and glasnost were terms Gorbachev used to embody his cultural reforms and openness to Western influence. The Chinese, too, had a period of openness. In 1956 Mao said that, “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” This “100 Flowers Movement” was ended in 1957 with political persecutions. Both Communist powers handled political dissonance in the second half of the 20th century differently, with the USSR embracing and the Chinese silencing controversy. Though, to look at it all now, the USSR has been disbanded and China is still heavily controlled by a limited ruling class.

Perestroika and glasnost were terms Gorbachev used to embody his cultural reforms and openness to Western influence. The Chinese, too, had a period of openness. In 1956 Mao said that, “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” This “100 Flowers Movement” was ended in 1957 with political persecutions. Both Communist powers handled political dissonance in the second half of the 20th century differently, with the USSR embracing and the Chinese silencing controversy. Though, to look at it all now, the USSR has been disbanded and China is still heavily controlled by a limited ruling class.