Category Archives: Uncategorized

Dickinson Summer Greek Workshop 2023: Plutarch, Bravery of Women

DICKINSON SUMMER GREEK WORKSHOP: JULY 17-21, 2023

Format: online only

Moderators: Prof. Mallory Monaco Caterine (Tulane University) and Prof. Scott Farrington (Dickinson College)

Our text for 2023 is Plutarch’s Mulierum Virtutes (“Bravery of Women”). Unlike Thucydides’ Pericles, Plutarch believed that the names of virtuous women ought to be widely known, and he produced this book, he tells us, to prove that womanly virtue and manly virtue are one and the same. Join us and delight in unsurpassed examples of courage and bravery from all over the ancient world. Learn how the Trojan women selected the site of Rome, how the women of Salmantica faced down Hannibal’s thugs, and how Valeria and Cloelia escaped the grip of Tarquin’s sons.

Mallory Monaco Caterine, Tulane University (PhD, Classics, 2013. Princeton University) Image source: Tulane University.

We will read the Greek text with vocabulary lists in the style of the Dickinson College Commentaries. We hope that this workshop will lead to the creation of a new commentary for DCC, and workshop participants will be invited to participate in that project.

The workshop will take place on Zoom from 1:00 to 4:30 p.m. Eastern Time, US.

TO APPLY: please email Mrs. Stephanie Dyson, Classical Studies Academic Department Coordinator (dysonst@dickinson.edu). Include your email and the name of the workshop you plan to attend. A non-refundable fee of $200.00 is due by June 1, 2023, in the form of a check made out to Dickinson College, mailed to Stephanie Dyson, Department of Classical Studies, Dickinson College, Carlisle PA 17013.

What would you like to see on DCC?

The 2023 meeting of the DCC Editorial Board centered around the creation of a wish list of texts that you, the discerning and valued DCC user, would like to see on the site. Quite a bit, including all of Eutropius, is in the pipeline. To get you thinking, here are some of the ideas we discussed. Please add your own thoughts in the comments here, send them to the DCC email account, (dickinsoncommentaries at gmail.com), or contact us via Twitter (@DCComm) or Facebook.

We began with the evident need for second-year Greek texts that are easier to read than, say, Plato. The lack of such texts results in much frustration at the lower intermediate level.

- Aesop’s fables.

- Selections from Apollodorus’ Library for the high-interest mythological content and the abundance of participles.

- Short and self-contained mythological narratives to be found in the Greek scholia. Much of the Homer and Euripides scholia are already online.

On the Latin side, much interesting Neo-Latin is right there for the editing:

- Rusticatio Mexicana as an excellent text both for its vivid descriptions of Mexico and because it is the first source for certain Native American legends.

- Sepulveda’s De Orbe Novo treats its subject in excellent Latin.

- Latin by women: the phenomenal Elizabeth Jane Weston, et aliae

- Latin translations of Greek classics, many of which exist in high quality early modern translations. Erasmus, for example, made verse translations of Greek tragedies that are excellent.

- Bilingual Latin editions of the Chinese classics, or the Koran.

We’re all for expanding the canon, but site analytics show that canonical authors are the most popular. What about:

- More Vergil. All of the Aeneid? Eclogues and Georgics? (Some are in the pipeline)

- Some Plato. He’s as relevant as ever, but we have none. There are many public domain editions from which to draw notes.

- Catullus. Some have found that even Garrison’s student-friendly edition does not provide enough help.

By far the most popular part of the site is not the commentaries but the reference works, like the core vocabularies, and above all Allen & Greenough’s Latin Grammar, which gets about 40% of our traffic. Should we go for more higher quality re-packaging of hard-to-use Perseus content, like

- Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology

- Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography

- Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb

Please do send us your thoughts, and when the time is right I will report back with the results in this space. There’s no telling what we will actually have the ability to produce, but with so many options, it will be very helpful indeed to have your suggestions.

Attendees of the 2023 DCC editorial board meeting.

Dickinson Digital Latin Workshop July 12-15, 2023

What: Dickinson Digital Latin Workshop

When: July 12-15, 2023

Where: Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania (in person only)

Intended for: all Latin teachers and students over 18 year of age. Requires no prior experience with computer programming. Intermediate and advanced programmers will still benefit from rethinking coding fundamentals through either a philological or a pedagogical lens.

Registration and fees: to register, please email Mrs. Stephanie Dyson, Classical Studies Academic Department Coordinator (dysonst@dickinson.edu) with your email address and the name of the workshop you plan to attend. A non-refundable fee of $200 is due by June 1, 2023 in the form of a check made out to Dickinson College, mailed to Stephanie Dyson, Department of Classical Studies, Dickinson College, Carlisle PA 17013. The fee includes lodging in campus housing (and please note that lodging will be in a student residence near the site of the sessions), two meals (breakfast and lunch) per day, as well as the opening dinner on the 12th.

Registered participants should plan to arrive in Carlisle, PA on July 12, in time to attend the first event of the seminar. This first event is an opening dinner and welcoming reception for all participants, which will begin at 6:00 p.m. The actual workshop sessions will begin early the next morning, on Thursday, July 13. The final event will be lunch on Saturday, July 15.

Content:

- teaches fundamentals of computational text analysis in the Python programming language using a corpus-driven, “exploratory” approach with activities focused on vocabulary and other formal textual features.

- introduces participants to the basics of computer programming while also demonstrating how learning to code can help with everyday tasks in the Latin classroom. Learn to write just enough code to build vocabulary lists, count frequent (and infrequent!) words, search texts in flexible and “fuzzy” ways, generate reading drills and exercises, build up a collection of word games, and more.

- helps participants develop computational skills useful for working with projects such as Dickinson College Commentaries and The Bridge.

Instructor

Patrick J. Burns, Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

Patrick J. Burns is Associate Research Scholar for Digital Projects at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, working previously at the Quantitative Criticism Lab at the University of Texas at Austin and the Culture, Cognition, and Coevolution Lab at Harvard University. Patrick is working an online book to be titled Exploratory Philology: Learning About Ancient Languages Through Computer Programming, a code-first introduction to Ancient Greek and Latin as well as a core contributor to the Classical Language Toolkit, a natural language processing framework for working with ancient-language text. Patrick has given workshops on digital and computational Classics topics at many venues, including Stanford, Yale, Dartmouth, NYU, Tufts, UT-Austin, Universität Rostock, and the Institute of Classical Studies.

Patrick J. Burns is Associate Research Scholar for Digital Projects at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University, working previously at the Quantitative Criticism Lab at the University of Texas at Austin and the Culture, Cognition, and Coevolution Lab at Harvard University. Patrick is working an online book to be titled Exploratory Philology: Learning About Ancient Languages Through Computer Programming, a code-first introduction to Ancient Greek and Latin as well as a core contributor to the Classical Language Toolkit, a natural language processing framework for working with ancient-language text. Patrick has given workshops on digital and computational Classics topics at many venues, including Stanford, Yale, Dartmouth, NYU, Tufts, UT-Austin, Universität Rostock, and the Institute of Classical Studies.

Description

What is the best way for Latin teachers and students to get started with computational approaches to working with texts? This three-day workshop introduces participants to the basics of computer programming while also demonstrating how learning to code can help with everyday tasks in the Latin classroom. Learn to write just enough code to build vocabulary lists, count frequent (and infrequent!) words, search texts in flexible and “fuzzy” ways, generate reading drills and exercises, build up a collection of word games, and more.

The workshop builds on the forthcoming book Exploratory Philology: Learning About Ancient Languages Through Computer Programming, a collection of text-analysis experiments designed to introduce coding to anyone interested in the Latin language and its literature. Building on Nick Montfort’s exploratory paradigm of learning how to “think with computation” as well as Marina Umaschi Bers’ pedagogical work on “coding as a playground,” Exploratory Philology offers a code-first, immersive and improvisational way of working with ancient-language text such that mutually reinforces the reader’s language skills and programming skills. While drawing extensively on material from Exploratory Philology, this workshop reframes the experiments from the book to address the specific pedagogical interests of Latin teachers and students, including by helping participants develop computational skills useful for working with projects such as Dickinson College Commentaries and The Bridge.

Agenda/Activities

- Day 1 (4 hours)

- Workshop overview / introductions

- Counting words, aka “exploratory philology” in medias res

- What is “Exploratory Philology”?

- Introduction to Classical Language Toolkit and CLTK Readers

- Breaking texts into smaller units (paragraphs, sentences, words, characters, and more)

- Making lists, making tables, making plots

- Day 2 (4 hours)

- The four Ds of Exploratory Philology w. coding activities

- Describe: Counting specific terms, spec. animals, colors, and more in Virgil

- Discover: Searching for alliteration in Ovid

- Deform: Autogenerating Latin sentence drills using Cicero

- Divert: Making Latin word scramble puzzles using Catullus

- Participant “Free Play” with the 4 Ds / Presentation Development

- Tips and tricks for Latin text analysis using the Natural Language Toolkit

- The four Ds of Exploratory Philology w. coding activities

- Day 3 (2 hours)

- Participant presentations

- Workshop conclusion/overview and participant feedback

Materials

The workshop uses several hands-on coding activities designed to help participants learn to read, write, and refactor computer programs for philological and pedagogical ends. All materials for the workshop are developed as Jupyter code notebooks and will be hosted in a public GitHub repository for participants’ reference after the workshop. Participants will also have the option of consulting the Exploratory Philology online book for further skill development.

Participants

The workshop has been designed for Latin teachers and students who can benefit from working with Latin text at scale and with greater automaticity and flexibility. No prior experience with computer programming necessary. All materials are provided as working code that participants are encouraged to revise and refactor for their own research and pedagogical applications. While the workshop is written in a way to be open to participants with no prior computer programming experience, intermediate and advanced programmers will still benefit from rethinking coding fundamentals through either a philological or a pedagogical lens.

Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop 2023: Navigatio Brendani

Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop 2023: Navigatio Brendani

July 7-12, 2023

The Dickinson Workshops are mainly intended for teachers of Latin, to refresh the mind through study of an extended text, and to share experiences and ideas. Sometimes those who are not currently engaged in teaching have participated as well, including students, retirees, and those working towards teacher certification.

St. Brendan and crew celebrate Easter on a whale.

Anonymous after Hendrick Goltzius, Stranded Whale at Zandvoort, 1594. Harvard Art Museum, Light Outerbridge Collection, Richard Norton Memorial Fund; British Library Manuscripts Harley 3244 & 4751.

The workshop will be conducted both in person and online. Participants may choose either option.

The text for 2023 is the legendary Christian tale of sea adventure, Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (“Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot”). This Irish epic, a narrative masterpiece, was recorded in Latin prose sometime between the mid-8th and early 10th century. According to the Navigatio, Brendan makes an astonishing Atlantic journey with other monks to the “Promised Land of the Saints” (later identified possibly as the Canary Islands), which he reaches after a prolonged search. The Navigatio was enormously popular in the Middle Ages, surviving in about 125 manuscripts, and the story was retold in Anglo-Norman, Dutch, German, Venetian, Provençal, Catalan, Norse and English.

We will read the Latin text with the help of the new commentary and vocabulary by Prof. William Turpin (Swarthmore College), which is forthcoming in Dickinson College Commentaries.

Moderators:

William Turpin, The Scheuer Family Chair of Humanities, Swarthmore College

Christopher Francese, Asbury J. Clarke Professor of Classical Studies, Dickinson College

Dr. Meghan Reedy (D. Phil., Oxford)

Drs. Turpin and Francese will moderate the in-person sections, Dr. Reedy the online group.

The participation fee for each participant will $400 for those attending in person, $200 for those attending online. The $400 fee for in person attendees covers lodging, breakfast and lunch in the Dickinson cafeteria, the facilities fee, which allows access to the gym, fitness center, and the library, as well as wireless and wired internet access while on campus. The fee does not cover the costs of books or travel, or of dinners, which are typically eaten in the various restaurants in Carlisle. Please keep in mind that the participation fee, once it has been received by the seminar’s organizers, is not refundable. This is an administrative necessity.

Lodging: accommodations will be in a student residence hall near the site of the sessions. The building features suite-style configurations of two double rooms sharing a private bathroom, or one double and one single room sharing a private bathroom.

The first event will be an introductory dinner at 6:00 p.m., July 7. The final session ends at noon on July 12. Sessions will meet from 8:30 a.m. to noon each day, with the afternoons left free for preparation.

Registration and fees: to register, please email Mrs. Stephanie Dyson, Classical Studies Academic Department Coordinator (dysonst@dickinson.edu). Include your email and the name of the workshop you plan to attend. A non-refundable fee of $400 is due by June 1, 2023 in the form of a check made out to Dickinson College, mailed to Stephanie Dyson, Department of Classical Studies, Dickinson College, Carlisle PA 17013.

For more information please contact Prof. Chris Francese (francese@dickinson.edu)

Dickinson Summer Greek Workshop: July 18-22, 2022

Dickinson Summer Greek Workshop: July 18-22, 2022

Moderators: Prof. Scott Farrington and Dr. Taylor Coughlan

Want to improve your reading fluency in Ancient Greek and learn more about ancient Greek culture? Please join us for the Dickinson Ancient Greek Workshop which will once again be held online this year. Though we’d prefer to welcome you all to campus, we hope that the greater flexibility of an online seminar will facilitate participation from people far and wide.

Marble head of an old fisherman (1st–2rd century A.D.

Roman, copy of a Greek statue of the late 2nd century B.C. Metropolitan Museum, New York)

This year’s text will be Lysias 24, On the Refusal of a Disability Benefit. Sometime in the early fourth century BCE, an Athenian citizen appeared before the Council to defend his qualifications to receive an annual state disability benefit. Revealing much about the treatment and status of non-elite citizens under democracy in Athens, the disabled pensioner delivers an innovative speech unique for its rhetorical use of humor. The defendant batters his opponent with sarcastic barbs and makes mockery of the entire legal affair. The Greek is accessible and lively. The text we will use is from a forthcoming Dickinson College Commentaries edition edited by Dr. Taylor Coughlan, Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Participants will have pre-publication access to Taylor’s notes as well as to interpretive essays and complete running vocabulary lists. A dictionary should not be necessary, particularly if you have mastered the DCC core Ancient Greek vocabulary.

Meetings

Online meetings will take place daily from 1:00 p.m. to 4:30 p.m., Eastern time US, with break in the middle. We will determine whether we meet in one section or two based upon enrollment.

Reading Schedule (projected)

Monday, July 18: Lysias 24.1-5

Tuesday, July 19: Lysias 24.6-10

Wednesday, July 20: Lysias 24.11-15

Thursday, July 21: Lysias 24.16-21

Friday, July 22: Lysias 24.22-27

If we read at a faster pace, we will also read selections from other speeches of Lysias.

Registration Fee

$200, due by check on or before July 1, 2022. Make checks payable to Dickinson College and mail them to

Department of Classical Studies, Dickinson College

c/o Stephanie Dyson

Carlisle, PA 17013

New at DCC: Homer, Odyssey 9-12

Thomas Van Nortwick and Rob Hardy’s commentary on Homer’s Odyssey Books 9-12 is now live. Like TVN’s other DCC commentary on Iliad 6 and 22 it has an extensive Introduction and fresh close reading essays on the whole. These essays are the fruit of a career’s-worth of research, reflection, and teaching and are not to be missed. Hang in there, Homerists, because another Van Nortwick-Hardy collaboration is in the works, Odyssey 5-8.

Photo credit: C. Francese,, Chanticleer Garden, Wayne, PA

These books of the Odyssey are already fairly well-served in school editions available in print, and in some cases online, aimed at students of Greek. Our edition is distinctive in the extent of the hyperlinking to reference resources in the notes, its full and accurate vocabulary lists, and the close reading essays for the entirety.

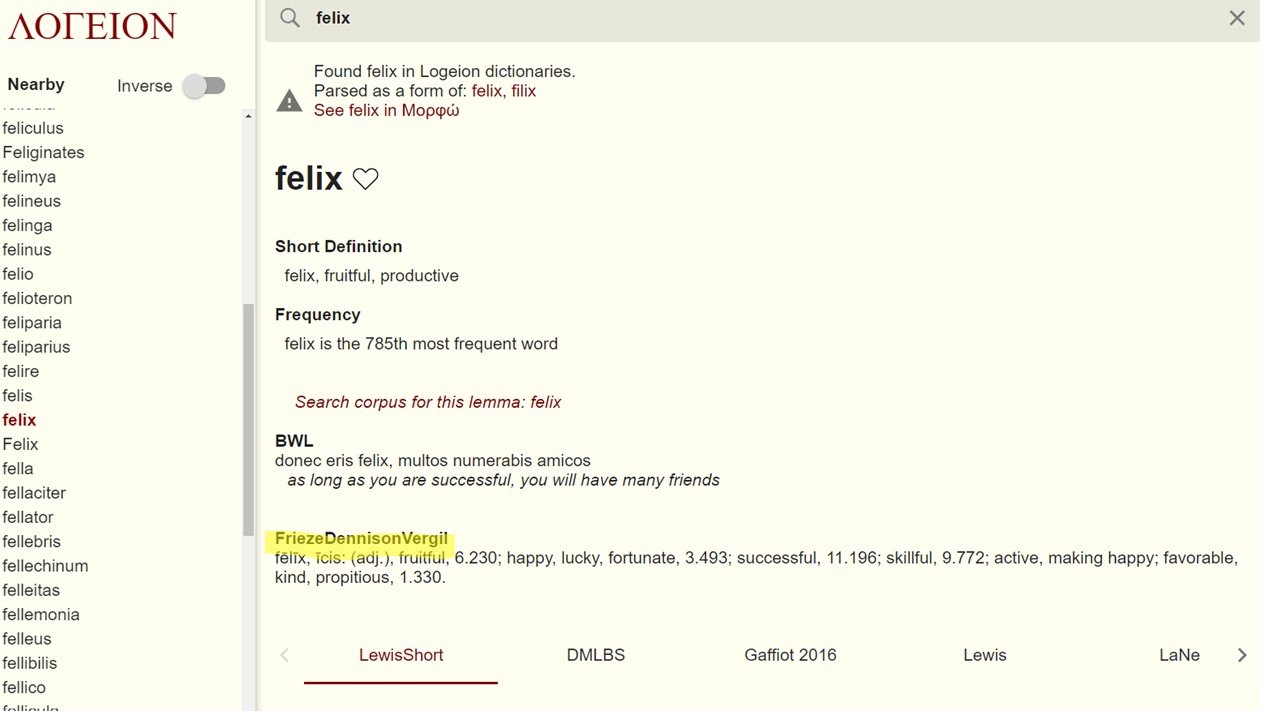

The notes are primarily grammatical, rather than interpretive. They focus on peculiarities of the Homeric dialect and the elucidation of expressions that do not easily yield sense when translated literally. They endeavor to be economical to encourage fluent reading but include hyperlinks to grammars and other reference resources for those seeking further details. Comparative passages are cited sparingly, but hyperlinked so they can be examined directly. Typical Homeric features such as definite articles used as pronouns, tmesis, and the omission of temporal augments, are pointed out. Unusual case usages and constructions are noticed and equipped with links to Smyth’s A Greek Grammar for Colleges (1920) at Perseus, or to Monro’s Grammar of the Homeric Dialect (1891) on DCC, and occasionally to Goodell’s School Grammar of Attic Greek (1902) on DCC. Verb forms that seem likely to cause puzzlement are parsed and the dictionary lemma given. Common words used in unusual senses are translated, often with a hyperlink to Logeion. Logeion now includes both Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon (1940) and Cunliffe’s Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect (1924), as well as Autenrieth’s Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges (1891). Linking to Logeion is intended to allow interested readers to get a fuller picture of the range of meanings that ancient Greek words can have, while also giving the opinion of the editor as to which specific sense is active in a particular passage. Another set of hyperlinks leads to the Homeric Paradigms which Seth Levin and Meagan Ayer developed for the DCC edition of Iliad Books 6 and 22, based on the charts in Pharr’s Homeric Greek: A Book for Beginners (1920). Links to these charts will allow interested readers to quickly look at all the common Homeric forms of paradigm nouns and verbs, as well as participles, pronouns, and irregular verbs. Because of the extensive occurrence of elision in Homer the notes often spell out a form where the elided letter may not be obvious. Rob Hardy’s Homeric Language Notes provides a summary of the points that recur in the notes and are especially pertinent for those coming to Homer from Attic Greek.

The lineage of our vocabulary lists is somewhat complex. The initial parsing of the text derives from the Perseids Project, which carried out human inspection of the entire text and the designated a specific dictionary lemma or headword for each word form. Bret Mulligan of the Haverford Bridge project equipped that parsed text with full dictionary forms and English definitions, though these full dictionary forms and definitions were often not the Homeric full dictionary forms and definitions. Extensive revision was necessary to fine tune the parsings, edit the dictionary forms to reflect the basics of Homeric usage, and to include English definitions that covered the Homeric meanings and were in contemporary English. This editing was performed over a long period by various people (see credits) using various resources, including the Homeric dictionaries available on Logeion and, more recently, the new Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (2015), which has been very helpful in modernizing the English for some definitions. As part of the editing process, the students who tested the commentary edited many of the definitions to make sure they were understandable to a modern audience. Many judgment calls had to be made about how many definitions and how much morphological information to include. The result is, I believe, the best Homeric reading vocabulary available. That is not to say that no infelicities remain, and I would be glad to receive notice of any issues you find or improvements you can suggest.

The notes and vocabulary lists were improved by testing and feedback from many students over several years, some of them from Louisiana State University, working with Willie Major, others from Dickinson, working with me, and others from Carleton College, working with Rob Hardy (see credits). The goal was to make sure that most of the kinds of questions that students have are answered economically in the notes, without adding too much in the way of ancillary information that would impede first time readers.

The Greek text conforms that of Allen’s Oxford Classical Text, with two exceptions.

- 9.239: M.L. West, in a paper left unfinished at his death but published later, makes a very good case for emending ἔκτοθεν of the manuscripts to ἔνδοθεν, so we have adopted that change.

- 12.171: Allen prints βάλον, where West’s 2016 Teubner edition prints θέσαν. Both have manuscript support, and we adopted West’s preferred reading.

Thomas Van Nortwick’s Introduction and essays, rather than attempting to survey all that has been written about these Books, point out significant parallels within and beyond the Homeric poems to show key themes and variations and bring out significant nuances that enrich our understanding of the text. He points to interesting ambiguities, helps us hear the tone, and see the many sides of Homer’s complicated hero. Each close reading essay includes suggestions for further reading.

How should one teach using this edition? Any way you like, but the inclusion of the running vocabulary lists makes it relatively easy to read this edition at sight. Many of the student test runs were carried on in this way. Students are assumed to know the DCC Core Ancient Greek vocabulary of 500 words before beginning, or else asked to learn sections of the core for homework. In class, the text is viewed side by side with the vocabulary list, either on Zoom for a virtual session or projected onto a screen in a classroom. If the instructor is sufficiently familiar with the notes, before too long students can work through the text fairly quickly without extensive dictionary time in preparation.

After a first pass at sight in class, homework can consist of re-reading the section and recording it aloud. The instructor can listen to the recording and determine if it shows comprehension, based on pausing, emphasis, and grouping of words. Other possible homework assignments might include morphology study, memorizing of short passages, or dictionary work (Find the five most important or emphatic words in the passage in your view; write the location in LSJ where the contextually appropriate meaning of each if these five words is listed; give the contextually appropriate translation of these five words; explain briefly why you believe each word is important in the context).

Extensive exposure leads to vocabulary acquisition, and the development of sight-reading skills engenders confidence. More subtly, the sight-reading approach re-orients attention in class toward syntax and endings, since these become key aids to making sense, rather than burdensome “extras” to be quizzed on after the work of translation is finished.

Though it bears a Dickinson imprimatur, this edition should really be considered an Oberlin product. Both Rob and I studied Homer for the first time with Tom Van Nortwick, Nate Greenberg, and Jim Helm at Oberlin in the mid 1980s. That rich and formative experience led us, multa per aequora, to this very pleasant collaboration. I am profoundly grateful to everyone who has been involved in this project, even if they have never met Tom Van Nortwick, whose gracious and humane teaching inspired its creation.

2022 Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop: Seneca’s Natural Questions

Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop: July 11-15, 2022

Moderators: Prof. Chris Francese and Dr. Meghan Reedy

The Dickinson Summer Latin Workshop will be held online this year. While this situation is far from ideal, we hope it will allow those who could not normally travel to Carlisle to participate.

First page of the manuscript De questionibus Naturalibus, made for the Catalan-Aragonese crown. Image: Wikipedia (Public Domain)

This year’s text is one seldom read these days, the Naturales Quaestiones of Seneca the Younger. This prose work concerns natural phenomena (rivers, earthquakes, wind, snow, meteors, and comets). It gives fascinating insights into ancient philosophical and scientific approaches to the physical world, and also vivid evocations of the grandeur, beauty, and terror of nature. Seneca also comments on aspects of Roman culture, such as the commercial trade in snow and the decadent (in his view) use of mirrors. The selections we will read are from a forthcoming Dickinson College Commentaries edition of selections from NQ edited by Prof. Chris Trinacty of Oberlin College. Participants will have pre-publication access to Chris’s detailed notes and vocabulary lists.

We are delighted to welcome back Dr. Meghan Reedy as guest instructor. She is a former Dickinson faculty member and is currently Program Coordinator with the Maine Humanities Council.

Meetings

- Online meetings will take place daily 1:00 p.m. to 4:30, Eastern time US, with a break in the middle. Group translation will be carried on in two sections, one for the more confident (affectionately known as “the sharks”), one for the less confident (even more affectionately known as “the dolphins”) led on alternating days by Reedy and Francese.

Reading Schedule (projected)

Monday, July 11: NQ 3 pref. 1-4, 3.15.1-8, 3.30-1-8

Tuesday, July 12: NQ 4a.2.12-15, 4b.13.1-11, 5.13.1-15.4

Wednesday, July 13: NQ 6.3.1-6.5.3, 6.8.1-6.10.2, 7.28.1-7.30.6

Thursday, July 14: NQ 1.pref. 5-13, 1.13.1-14.6, 1.17.1-10

Friday, July 15: NQ 2.36.1-38.4, 2.59.1-13.

Registration Fee

$200, due by check on or before July 1, 2022. Make checks payable to Dickinson College and mail them to

Department of Classical Studies, Dickinson College

c/o Stephanie Dyson

Carlisle, PA 17013

Hack Your Latin Supplemental: Get a Grip on quidem

Fontaine scripsit

Get a grip on quidem. It’s a particle, one of the only ones in Latin. Either translate it “yes” or “(it’s) true” or don’t translate it at all. It implies or points forward to a contrast, usually marked by the word sed (but). For example, the sentence homo stultus quidem est, sed bonus means “The guy is an idiot, it’s true, but he’s good.” You could also translate that “The guy is an idiot, yes, but he’s good” or “The guy is an idiot, but he’s good.” Never translate it “indeed” since it doesn’t mean that in the English of 2016.

aliqua exempla collegi

meus vir hic quidem est. “This is my husband” (Plaut. Amph. 660)

me quidem praesente numquam factum est, quod sciam. “This never happened in my presence, as far as I know.” (Plaut. Amph. 749)

facile id quidem edepol possum, si tu vis. “I can easily do that, if you want.” (Plaut. Cist. 234)

ne id quidem tam breve spatium potest opitulari. “Not even that brief amount of time can help.” (Cornelia, mater Gracchorum, epistula, fragmenta 2.8)

nimis stulte faciunt, mea quidem sententia. “They behave very stupidly, in my opinion.” (Plaut. Men. 81)

adeo veritatis diligens, ut ne ioco quidem mentiretur. “So careful about the truth that he did not lie even for a joke.” (Nepos Epam. 3)

utinam quidem istuc evenisset! Sed non accidit. “If only it had turned out that way! But it did not happen.” (Nepos Eum. 11)

simulacrum Cereris unum, quod a viro non modo tangi sed ne aspici quidem fas fuit. “A statue of Ceres that it was forbidden for men to touch, or even to look at.” (Cic. In Verr. 2.5.187)

How consistent is Latin punctuation in PHI?

Latin punctuation is one of those classicist trade-secret things. To understand it fully takes intense study, and most classicists have views, no doubt dogmatically held. I am no purist. The bottom line for me is that Latin punctuation is just not as rule-bound as punctuation in English. Not that that is a bad thing. It’s just a different tradition. School texts have far more punctuation than scholarly critical editions. Some of the I Tatti editions seem almost allergic to punctuation. Editing a Neo-Latin text has made me newly aware of this issue, since I am frequently having to make decisions about where to put commas (trying to keep them to a minimum consistent with clarity), whether to use semi-colons (almost never), and so on. Early modern printed editions are notoriously punctuation happy. It sometimes seems as if the printer loaded a shotgun with commas, colons, and periods and fired at the page. Here is a taste:

Joannis Petri Maffeii Bergomatis E Societate Jesu Historiarum Indicarum Libri XVI (Vienna: Bernardi, 1752; orig. 1588), p. 6.

A more minimal, modern punctuation might be:

… illud praesertim summo conatu pervestigare num quis ab Atlantico in Eoum Oceanum vel mari vel terra transitus foret. Quippe iam tum, praeter acerrimum propagandae Christianae fidei studium, ad beatas etiam Arabiae gazas et Indici litoris opulenta commercia mentem et cogitationem adiecerat.

Although as a rule I would rather not have commas around prepositional phrases like praeter .. studium, it seems useful for comprehension in this case.

Various authors have explained their practices recently. My main guides are Cynthia Damon, who has an excellent discussion in the preface to her Oxford Classical Text of Caesar’s De bello civili, and Milena Minkova, whose wonderful Neo-Latin anthology I recommend heartily to anyone who wants to sample the best Latin writing in the early modern period. They both recommend a restrained approach, but Minkova insists that ablatives absolute, for example, should almost always be enclosed in commas. Damon (wisely, in my view) reserves semi-cola for independent clauses in indirect discourse. Given the flexibility available to editors, the golden rule is: a well-punctuated text shows that the editor understands the text.

In investigating this issue I have been intrigued to see the degree of variation among the modern edited texts (mostly Teubners and OCTs) reproduced in PHI, and I have never seen any collection of instances of variation or consensus among them. So, for those who might be interested in such things, here is my working list. The second column represents my policy, based on my own intuition and observations from PHI.

| non modo …, sed | include the comma before sed | |

| partim …, partim | include the comma before the second partim | |

| dubium quin | no comma before quin in phrases like “neque erat dubium quin” | |

| ea lege ut | comma before ut? PHI examples go both ways | |

| non tam X … quam Y | usually no comma | |

| adeo … ut |

comma before ut? Editors seem to differ a lot on this point. Some religiously include it (e.g. Marshall’s Nepos), others tend not to. In the Livy editions on PHI they tend to leave it out, which I prefer in most circumstances.

|

|

| primum … dein | clauses usually separated by comma if short, semi-colon if longer | http://latin.packhum.org/search?q=%5BLiv%5D+primum+~+Dein%23 |

| his dictis | no comma after this introductory formula | |

| factum est ut | comma after est? editors seem to vary on this | |

| eo magis quod | comma after magis? Generally not | |

| vel … vel | This seems to vary a bit, but generally comma can be omitted before the second vel | |

| introductory ablative absolute | These seem to go without a comma if they are only two or three words | |

| x adiuvante | no need for commas around this kind of very short ablative absolute | |

| primo … ; dein | or primo … dein, or primo …. Dein? Check out the examples from Livy | |

| postremo, |

make sure to use the comma if a subordinate clause (ubi, cum), or abl. abs., immediately follows.

|

|

| ut fit, ut assolet |

these parenthetical expressions are normally enclosed in commas, though sometimes ut fit is not in PHI

|

|

| is cum | no comma |