Thomas Van Nortwick and Rob Hardy’s commentary on Homer’s Odyssey Books 9-12 is now live. Like TVN’s other DCC commentary on Iliad 6 and 22 it has an extensive Introduction and fresh close reading essays on the whole. These essays are the fruit of a career’s-worth of research, reflection, and teaching and are not to be missed. Hang in there, Homerists, because another Van Nortwick-Hardy collaboration is in the works, Odyssey 5-8.

Photo credit: C. Francese,, Chanticleer Garden, Wayne, PA

These books of the Odyssey are already fairly well-served in school editions available in print, and in some cases online, aimed at students of Greek. Our edition is distinctive in the extent of the hyperlinking to reference resources in the notes, its full and accurate vocabulary lists, and the close reading essays for the entirety.

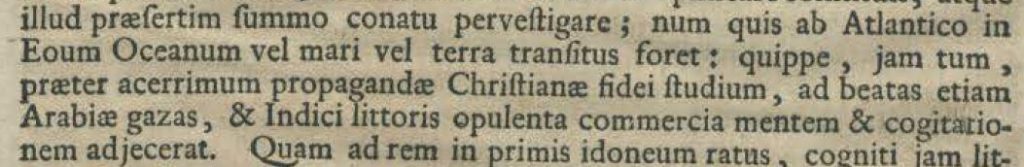

The notes are primarily grammatical, rather than interpretive. They focus on peculiarities of the Homeric dialect and the elucidation of expressions that do not easily yield sense when translated literally. They endeavor to be economical to encourage fluent reading but include hyperlinks to grammars and other reference resources for those seeking further details. Comparative passages are cited sparingly, but hyperlinked so they can be examined directly. Typical Homeric features such as definite articles used as pronouns, tmesis, and the omission of temporal augments, are pointed out. Unusual case usages and constructions are noticed and equipped with links to Smyth’s A Greek Grammar for Colleges (1920) at Perseus, or to Monro’s Grammar of the Homeric Dialect (1891) on DCC, and occasionally to Goodell’s School Grammar of Attic Greek (1902) on DCC. Verb forms that seem likely to cause puzzlement are parsed and the dictionary lemma given. Common words used in unusual senses are translated, often with a hyperlink to Logeion. Logeion now includes both Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon (1940) and Cunliffe’s Lexicon of the Homeric Dialect (1924), as well as Autenrieth’s Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges (1891). Linking to Logeion is intended to allow interested readers to get a fuller picture of the range of meanings that ancient Greek words can have, while also giving the opinion of the editor as to which specific sense is active in a particular passage. Another set of hyperlinks leads to the Homeric Paradigms which Seth Levin and Meagan Ayer developed for the DCC edition of Iliad Books 6 and 22, based on the charts in Pharr’s Homeric Greek: A Book for Beginners (1920). Links to these charts will allow interested readers to quickly look at all the common Homeric forms of paradigm nouns and verbs, as well as participles, pronouns, and irregular verbs. Because of the extensive occurrence of elision in Homer the notes often spell out a form where the elided letter may not be obvious. Rob Hardy’s Homeric Language Notes provides a summary of the points that recur in the notes and are especially pertinent for those coming to Homer from Attic Greek.

The lineage of our vocabulary lists is somewhat complex. The initial parsing of the text derives from the Perseids Project, which carried out human inspection of the entire text and the designated a specific dictionary lemma or headword for each word form. Bret Mulligan of the Haverford Bridge project equipped that parsed text with full dictionary forms and English definitions, though these full dictionary forms and definitions were often not the Homeric full dictionary forms and definitions. Extensive revision was necessary to fine tune the parsings, edit the dictionary forms to reflect the basics of Homeric usage, and to include English definitions that covered the Homeric meanings and were in contemporary English. This editing was performed over a long period by various people (see credits) using various resources, including the Homeric dictionaries available on Logeion and, more recently, the new Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (2015), which has been very helpful in modernizing the English for some definitions. As part of the editing process, the students who tested the commentary edited many of the definitions to make sure they were understandable to a modern audience. Many judgment calls had to be made about how many definitions and how much morphological information to include. The result is, I believe, the best Homeric reading vocabulary available. That is not to say that no infelicities remain, and I would be glad to receive notice of any issues you find or improvements you can suggest.

The notes and vocabulary lists were improved by testing and feedback from many students over several years, some of them from Louisiana State University, working with Willie Major, others from Dickinson, working with me, and others from Carleton College, working with Rob Hardy (see credits). The goal was to make sure that most of the kinds of questions that students have are answered economically in the notes, without adding too much in the way of ancillary information that would impede first time readers.

The Greek text conforms that of Allen’s Oxford Classical Text, with two exceptions.

- 9.239: M.L. West, in a paper left unfinished at his death but published later, makes a very good case for emending ἔκτοθεν of the manuscripts to ἔνδοθεν, so we have adopted that change.

- 12.171: Allen prints βάλον, where West’s 2016 Teubner edition prints θέσαν. Both have manuscript support, and we adopted West’s preferred reading.

Thomas Van Nortwick’s Introduction and essays, rather than attempting to survey all that has been written about these Books, point out significant parallels within and beyond the Homeric poems to show key themes and variations and bring out significant nuances that enrich our understanding of the text. He points to interesting ambiguities, helps us hear the tone, and see the many sides of Homer’s complicated hero. Each close reading essay includes suggestions for further reading.

How should one teach using this edition? Any way you like, but the inclusion of the running vocabulary lists makes it relatively easy to read this edition at sight. Many of the student test runs were carried on in this way. Students are assumed to know the DCC Core Ancient Greek vocabulary of 500 words before beginning, or else asked to learn sections of the core for homework. In class, the text is viewed side by side with the vocabulary list, either on Zoom for a virtual session or projected onto a screen in a classroom. If the instructor is sufficiently familiar with the notes, before too long students can work through the text fairly quickly without extensive dictionary time in preparation.

After a first pass at sight in class, homework can consist of re-reading the section and recording it aloud. The instructor can listen to the recording and determine if it shows comprehension, based on pausing, emphasis, and grouping of words. Other possible homework assignments might include morphology study, memorizing of short passages, or dictionary work (Find the five most important or emphatic words in the passage in your view; write the location in LSJ where the contextually appropriate meaning of each if these five words is listed; give the contextually appropriate translation of these five words; explain briefly why you believe each word is important in the context).

Extensive exposure leads to vocabulary acquisition, and the development of sight-reading skills engenders confidence. More subtly, the sight-reading approach re-orients attention in class toward syntax and endings, since these become key aids to making sense, rather than burdensome “extras” to be quizzed on after the work of translation is finished.

Though it bears a Dickinson imprimatur, this edition should really be considered an Oberlin product. Both Rob and I studied Homer for the first time with Tom Van Nortwick, Nate Greenberg, and Jim Helm at Oberlin in the mid 1980s. That rich and formative experience led us, multa per aequora, to this very pleasant collaboration. I am profoundly grateful to everyone who has been involved in this project, even if they have never met Tom Van Nortwick, whose gracious and humane teaching inspired its creation.