May 16 2021

IV. Essays und autobiografische Texte: Heimatbilder, Grenzgebiete

Heimat und Identitätspolitik in

Grenzgebieten am Eisernen Vorhang

von Stettin bis zum Dreiländereck

im Burgenland:

Vom Kalten Krieg bis zur

Vereinigung Europas

Edith Borchardt, Morris, Minnesota

Das Haus, in dem ich mit meinen Eltern nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg wohnte, steht nicht mehr, doch die Adresse ist erhalten geblieben. Heute ist es die Wohnanlage Münchner Straße 10 mit einem Computer-Store und Jeansgeschäft, wo es früher bei Bauer Tabakwaren und Lebensmittel zu kaufen gab. Rechtsanwälte und Steuerberater haben jetzt dort ihre Büros, und durch die gläserne Eingangstür kann man in der hellen neuen Eingangshalle moderne Postkästen sehen. Vor dem Abbruch des Altbaus haben Türken in unserer Wohnung gelebt. Auf mein Klingeln hin ließ mich ein kleiner schwarzhaariger Junge in den Flur, der zum Treppenhaus und hinten hinaus zum Garten führte. Vom Treppenabsatz blickte ich durch das kleine Fenster hinunter in den Garten, der an den Pfarrhof der evangelischen Kirche stieß. Über den Zaun hingen die Zweige des Nussbaums vom anderen Grundstück, und der hochragende Sattelturm mahnte immer noch zum Besuch des sonntäglichen Gottesdienstes.

Auf den Marktplatz unserer Kleinstadt mit der Leonhardikapelle an der Amper kam nach dem Krieg regelmäßig eine Leihbibliothek auf Rädern mit amerikanischen Büchern in deutscher Übersetzung. Heute weiß ich, dass das eine Maßnahme zur kulturellen Steuerung in der südlichen Besatzungszone war, denn die Sieger wollten ein positives Bild von Amerika verbreiten. Mir geriet damals ein Band in die Hände, in dem es um das Leben einer Familie auf der Prärie im Mittelwesten Amerikas ging. Was mich beim Lesen am meisten beeindruckte, waren die Schneestürme, die in dem Roman eine große Rolle spielten. Es war mir unvorstellbar, dass der Weg vom Haus zu den Ställen durch Wind und Schneewehen lebensgefährlich werden konnte und man sich an Stricken entlangtasten musste, um sich nicht zu verirren und in den sich leise anhäufenden Schneemassen zu erfrieren. Später, als ich in Kalifornien Germanistik studierte, erzählte mir eine Kanadierin aus Alberta, die auch im Internationalen Haus in Berkeley lebte, von der Kälte im Steppenland des nordamerikanischen Kontinents, wo minus 40 Grad keine Seltenheit waren. Wie konnte ich als Schülerin vor dem Wirtschaftswunder ahnen, dass mein Lebensweg mich einmal, wenn auch auf mancherlei Umwegen, in diesen amerikanischen Mittelwesten führen würde, an die Universität von Minnesota, wo ich jahrzehntelang deutsche Literatur, Sprache und Kultur unterrichten und selbst solche Schneestürme auf der Prärie erleben sollte?

In meiner kindlichen Unbefangenheit im Nachkriegsdeutschland wusste ich nicht, warum die „kulturelle Diplomatie“ der amerikanischen Leihbibliotheken notwendig war und dass sie Hand in Hand mit dem Marshall-Plan ging, der dazu bestimmt war, Deutschland beim Wiederaufbau zu unterstützen. Er war die Gegenbewegung zum sowjetischen Einfluss in den westlichen Besatzungszonen nach der Berliner Blockade durch die Russen und folgte der rettenden Luftbrücke der Amerikaner, die Deutschland daraufhin in ein demokratisches Europa mit neuen Industrien integrieren wollten. Dass es auch anders hätte kommen können, erfuhr ich erst Jahrzehnte später in einem Filmkurs in Berkeley, einem Sommerseminar, in dem ich Fassbinders Die Ehe der Maria Braun sah. In einer Radiosendung hört man da von dem Morgenthau-Plan von 1944, in dem der damalige amerikanische Finanzminister Henry Morgenthau Jr. aus Poughkeepsie – ein enger Freund von Franklin Delano Roosevelt, der nicht weit entfernt in Hyde Park lebte – vorschlug, Deutschland nach dem Sieg der Alliierten in einen Agrarstaat zu verwandeln. Die Fabriken, die im Krieg Waffen hergestellt hatten, sollten abgebaut und Bergwerke und Kohlegruben geschlossen werden, „alles … sollte dem Erdboden gleichgemacht werden“, damit Deutschland nie wieder Krieg führen könnte. Außerdem wollte Morgenthau Deutschland in einen Nord- und einen Südstaat trennen und deutsche Gebiete an Frankreich, Dänemark, Polen und die Sowjetunion übertragen. Deutschland sollte das industrielle Ruhrgebiet total verlieren und Deutsche sollten als Zwangsarbeiter ins Ausland gebracht werden.[1] Durch die Berliner Blockade kam jedoch alles anders. Der Streit zwischen Amerika und der russischen Besatzung um die Regierung Berlins löste den ideologischen Kampf zwischen Amerika und der Sowjetunion aus, den Kalten Krieg, der sich über 40 Jahre hinzog und auch mein eigenes Leben direkt betraf. Bei der offiziellen Teilung Deutschlands 1949 war ich in der ersten Klasse, erlebte aber erst in der dritten den Zustrom von Flüchtlingen aus dem Osten nach dem Krieg, ohne zu wissen, warum plötzlich neue Schüler aus Schlesien und Thüringen zu uns kamen, die einen anderen Dialekt sprachen und mit ihren Familien Hab und Gut im „anderen“ Deutschland zurückgelassen hatten.

Der Anfang des Kalten Krieges kann auch Winston Churchill zugeschrieben werden, der 1946 in seiner berühmten Rede am Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, vom Eisernen Vorhang sprach, der sich von Stettin an der Ostsee bis Trieste am Adriatischen Meer hinziehen und das westliche Europa von der Sowjetunion und ihren im Krieg eroberten Satellitenstaaten trennen sollte.[2] Wie später die Mauer in Berlin, zerstörte er die Zugehörigkeit von Familien, die in den Gebieten lebten, durch die sich diese neuen Grenzen zogen. Mein Vater kam aus Pommern, aus der Nähe von Stettin, das heute polnisch ist. Er wuchs bei seiner Großmutter in Brandenburg bei Berlin auf, dessen Geschichte, Landschaft und Menschen Theodor Fontane in seinen Wanderungen durch die Mark Brandenburg eingehend beschrieben hat. Nach Ende des Krieges hat mein Vater seine Heimat hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang nie wiedergesehen. Von seiner Familie hat, soviel ich weiß, niemand den Krieg überlebt. Seine drei Schwestern hätte ich gerne kennengelernt. Sie hießen Brünhild, Sieglind und Kriemhild. Meine Internetsuchen sind aber vergeblich. Auch mit der Angabe des Familiennamens weisen sie immer nur auf Richard Wagners Ring und das Nibelungenlied zurück. Von meiner Urgroßmutter väterlicherseits besitze ich ein kleines Schwarzweiß-Foto, in dem sie im hohen Alter irgendwo in einem winterlichen Garten mit gefalteten Händen auf einem Stuhl umgeben von Schneeresten sitzt. Ihr Haar ist sorgfältig in einen Knoten nach hinten gekämmt, und sie scheint so viele Röcke zu tragen wie die kaschubische Großmutter am Anfang der Blechtrommel von Günter Grass. Ihre Augen sind geschlossen, und auf ihrem Antlitz ruht ein fast überirdisches Lächeln. Sie ist 96 Jahre alt geworden und hätte vielleicht noch länger gelebt, meinte mein Vater, wenn die Russen sie am Ende des Krieges nicht tief im Winter in die Kälte hinausgesetzt hätten, um sie erfrieren zu lassen. Er selbst wurde 95 Jahre alt. In den Tagen vor seinem Tod rief er immer nach Henrik, und als ich ihn fragte, wer das denn sei, antwortete er: „Das ist mein Bruder.“ Mehr sagte er nicht und zog sich zurück in sein Mittagsschläfchen.

***

Auf der Suche nach der Vergangenheit: „Ich hab’ noch einen Koffer in Berlin…“

In ihrer Jugend lebten meine Eltern einige Zeit in Berlin und schwärmten für diese Stadt, bevor sie im Krieg zerstört wurde. Kurz nachdem wir nach New York kamen, brachten sie vom deutschen Metzger, der auch deutsche Zeitungen und Zeitschriften verkaufte, eine Schallplatte mit Berliner Liedern nach Hause, die wir in unserem neuen Grundig Musikschrank spielten. Alles, was ich von Berlin als Teenager wusste, lernte ich von dieser Langspielplatte: Dort hörte ich zum ersten Mal Lieder wie „Untern Linden, Untern Linden“, „Im Grunewald, im Grunewald ist Holzauktion“ und „Durch Berlin fließt immer noch die Spree“ sowie „Ich hab so Heimweh nach dem Kurfürstendamm“. Das freie Berlin, nach dem Krieg von der Mauer umgeben, war gefangen im kommunistischen Osten und lange nicht leicht zugänglich. Erst 31 Jahre später konnte ich auf der Spur der ehemaligen Mauer mit Kollegen aus Amerika spazierengehen.

Zu einem Symposium mit Schriftstellern aus der ehemaligen DDR war ich nach dem Fall der Mauer 1992 zu Gast in Berlin an der Freien Akademie und erfuhr, dass mein Familienname in dieser Gegend weit verbreitet ist. Die Freie Akademie in Grunewald, dem eleganten Villen- und Botschaftsviertel von Berlin, wollte Brücken schlagen zwischen Ost und West und zu gegenseitigem Verständnis nach der Wende beitragen. Günter de Bruyn und Helga Schubert sprachen zu uns über das Leben unter der Regierung von Erich Honecker, über die Bespitzelung im Schriftstellerverband der DDR von der Stasi im sozialistischen Staat und sogar auch von den eigenen Mitgliedern. Mit anderen Tagungsteilnehmern fuhr ich mit dem Bus durch den Grunewald und am Wannsee vorbei, wo die Vertreter der deutschen Reichsregierung 1942 beschlossen, alle Juden Europas zur Vernichtung in Konzentrationslager in den Osten zu befördern. Das Protokoll für die „Endlösung“ wurde von Adolf Eichmann handschriftlich aufgenommen. Villa Wannsee ist heute eine Gedenkstätte für den Holocaust. In Potsdam besuchten wir Sanssouci, das so kurz nach der Wende gerade renoviert wurde und von Baugerüsten umgeben war, denn die sozialistische Regierung der DDR hatte nach dem Krieg die Denkmäler der deutschen Monarchie aus ideologischen und möglicherweise finanziellen Gründen total vernachlässigt. Unsere Tour führte uns auch zu Schloss Cäcilienhof, wo das Potsdamer Abkommen unterzeichnet wurde, in dem Stalin, Truman und Churchill im August 1945 die politische und geographische Neuordnung Deutschlands, Reparationen und die Entmilitarisierung des Landes beschlossen.

© wikipedia: Potsdamer Abkommen 1945: Churchill, Truman, Stalin |

Ein übergroßes Porträt dieser Regierungsoberhäupter hängt in einem der hohen, holzgetäfelten Säle. Die Siegermächte entschieden hier, dass Stettin und somit die Heimat meines Vaters unter polnische Verwaltung kommen würde. Mehr als zwei Millionen Deutsche aus der Kurmark, Brandenburg und Pommern verloren wegen dieses Abkommens ihre Heimat durch Zwangsumsiedlungen und Vertreibungen, darunter wahrscheinlich auch die spurlos verschwundenen Verwandten meines Vaters, die trotz Nachforschungen übers Rote Kreuz unauffindbar blieben. Ungefähr 600.000 Deutsche kamen von 1944 bis 1947 bei Flucht oder Vertreibung ums Leben. Bis Ende der fünfziger Jahre kamen noch Millionen Aussiedler oder Vertriebene in beide Staaten des geteilten Deutschland,[3] manche von ihnen wohl die kleinen Flüchtlinge, die plötzlich in der dritten Klasse bei mir in Bayern auftauchten.

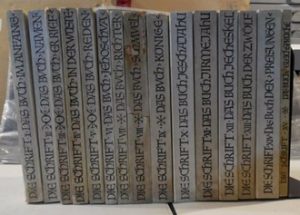

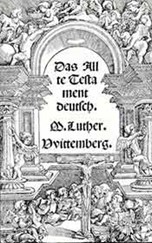

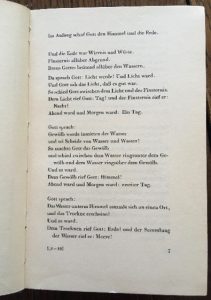

1999 hielt ich in Berlin-Schmöckwitz einen Vortrag über das Vereinte Europa auf dem Campus der Teikyo Universität, im früheren Osten von Berlin, zehn Jahre nachdem die Mauer und der Eiserne Vorhang gefallen waren. Ein türkischer Taxifahrer, der fabelhaft Deutsch sprach, brachte mich vom Flughafen zum Tagungszentrum, das ganz idyllisch am Zeuthener See an der Grenze zu Brandenburg liegt. Das Thema der Konferenz war „The New Europe at the Crossroads“. Im Zusammenhang mit den Erwartungen für ein Vereintes Europa, das sich nach der Auflösung des Kommunismus in Mittel- und Osteuropa Frieden auf dem Kontinent erhoffte, sprach ich über Novalis, Eméric Crucé und Rudolf von Habsburg. 200 Jahre vorher hat Novalis zur Zeit der Frühromantik im Chaos der Napoleonischen Kriege die Einheit Europas im katholischen Mittelalter in seinem Aufsatz „Die Christenheit oder Europa“ idealisiert und poetisiert und den Zerfall des universalen Christentums in der Zersplitterung der Religion durch Luther, die Deisten und Enzyklopädisten im Prozess der Säkularisierung über Jahrhunderte hinweg gesehen. Goethe, der auch die Napoleonischen Kriege erlebte, kommentiert im Faust den Zerfall des Römischen Reiches durch die spöttelnden Studenten in Auerbachs Keller: „Das liebe Heil’ge Röm’sche Reich, / Wie hält’s nur noch zusammen?“ Bei Novalis ging es um die Erneuerung und Identität des christlichen Westens, der – wenn Novalis auch davon schweigt – oft dem Ansturm der Türken aus dem Osmanischen Reich ausgesetzt war. Wiederholt (1529, 1683) wurden die Osmanen an den Toren von Wien im Habsburgerreich zurückgeschlagen.

In seinem Werk Le Nouveau Cynée von 1623 war Eméric Crucé der Meinung, dass ein dauernder Frieden in Europa nur hergestellt werden könnte, wenn Christen und Muslime sich nicht länger als Feinde betrachteten und Kriege gegeneinander führten. Diese Idee war besonders relevant zur Zeit beider Tagungen in Berlin, weil damals (1991–1999) noch die ethnischen Kriege in Jugoslawien wüteten, die zum Teil auf religiösen Unterschieden beruhten. Ein paar Jahre später, infolge der Kriege im Mittelosten, sagten die extrem militanten Terroristen des Islamischen Staats im Irak und in Syrien dem Westen den Krieg an, womit sie den Frieden und die Sicherheit auf allen Kontinenten bedrohten. Eméric Crucé war seiner Zeit weit voraus, indem er schon Anfang des 17. Jahrhunderts eine Weltordnung voraussah, die auf religiöser Freiheit und einer freien Marktwirtschaft beruhte, eine Welt, in welcher der Frieden durch eine weltweite Organisation erhalten bliebe, zu der alle freien Länder und Nationen gehörten. Streitigkeiten sollten durch wirtschaftliche und diplomatische Lösungen beseitigt werden, und militärische Eingriffe sollten nur in Notfällen stattfinden. Der Zoll an den Grenzen Europas sollte abgeschafft werden, um den Handel zu fördern und alle Länder wirtschaftlich zu fördern und zu stabilisieren. Der Frieden sollte durch globales Denken gesichert werden und durch die Idee der gemeinsamen Menschlichkeit.[4] Viele seiner Ideen sind seit der Gründung des Vereinten Europas verwirklicht worden, wenn auch Frieden auf der Welt weiterhin ein utopisches Ideal bleibt. Auf einer Rundfahrt in Berlin auf der Spree hörte ich im Boot hinter mir ein Konferenzmitglied aus Albanien zu anderen von seiner Hoffnung sprechen, dass auch das Osmanische Reich in seiner früheren Herrlichkeit wiederaufgebaut werden könnte.

Rudolf von Habsburg war der Meinung, dass das Reich, das er einmal erben sollte, die Doppelmonarchie an der Donau, schon ein Vereintes Europa in Miniatur war. An Georges Clemenceau schrieb er im Dezember 1886: „Österreich ist ein Staatenblock verschiedenster Nationen und verschiedenster Rassen unter einheitlicher Führung. Jedenfalls ist das die grundlegende Idee eines Österreich, und es ist eine Idee von ungeheuerster Wichtigkeit für die Weltzivilisation.“[5]

|

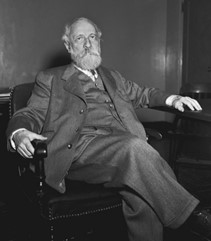

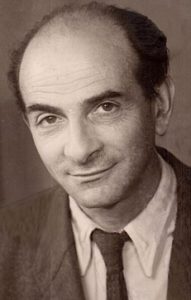

Otto von Habsburg,[6] der Sohn des letzten Kaisers von Österreich, Kronprinz und Thronerbe des vergangenen Reiches, half als Mitglied des Europäischen Parlaments in Brüssel von 1979–1999, Rudolfs Ideal der Vereinigten Staaten von Europa zu verwirklichen. Die Europäische Union geht aber weit über die Grenzen des damaligen Habsburgerreichs hinaus und umfasst nicht nur alle Länder des mittelalterlichen Heiligen Römischen Reiches, sondern auch Länder in Mittel- und Osteuropa, die nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg sowjetische Satellitenstaaten waren. Der Eiserne Vorhang und die Mauer mussten fallen, damit diese Staaten in ein freies, demokratisches Europa integriert werden konnten. Otto von Habsburg hat als neues Mitglied im Europäischen Parlament 1979 einen unbesetzten Stuhl für die Länder auf der anderen Seite des Eisernen Vorhangs aufstellen lassen[7] und ein starkes Interesse für diese Länder gezeigt, die vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg zum Habsburgerreich gehört hatten. Er selbst war mitbeteiligt an der Planung für das Pan-Europäische Picknick in Sopron, einer Friedensdemonstration auf der ungarischen Seite des Eisernen Vorhangs am 19. August 1989.[8] Er wollte feststellen, ob der russische Generalsekretär Michail Gorbatschow Offenheit für eine Änderung der gegenwärtigen Zustände zeigen würde. Dieses Picknick bewirkte eine Kettenreaktion, durch welche die DDR und der Ostblock zu Fall kamen. Otto von Habsburg erwähnte die Idee, den Eisernen Vorhang zu öffnen, gegenüber Miklós Németh, dem ungarischen Premier von 1988-1990, der den Plan in Aktion umsetzte.[9]

***

Reiten, reiten, reiten, durch den Tag, durch die Nacht, durch den Tag. Reiten, reiten, reiten. Und der Mut ist so müde geworden und die Sehnsucht so groß. Es gibt keine Berge mehr, kaum einen Baum…. Nirgends ein Turm. Und immer das gleiche Bild…. Vielleicht kehren wir nächtens immer wieder das Stück zurück, das wir in der fremden Sonne mühsam gewonnen haben?

So erlebt der junge Fahnenträger in Rilkes „Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke“ das ungarische Flachland, das er im Vierten Krieg Österreichs gegen die Türken (1663-1664) unter Generalfeldmarschall Johann von Sporck durchzieht. Seine Kompagnie liegt jenseits der Raab, die in Györ in die Mosoni Duna, einen Seitenarm der Donau, mündet. Aus dieser Gegend stammt meine Mutter, die im heutigen Komitat Györ-Moson-Sopron (Raab-Wieselburg-Ödenburg) in Ungarn zur Welt kam. Sie wuchs aber nicht in Ungarn auf, weil das heutige Burgenland, das deutschsprachige Westungarn, nach dem 1. Weltkrieg durch den Friedensvertrag von Trianon (im Juni 1920) und die Unterzeichnung der Venediger Protokolle (im Oktober 1921) offiziell zu Österreich kam.[10] Ihr Geburtsort, Mosonmagyaróvár, blieb bei Ungarn, aber ihre Eltern bauten ein Haus auf der anderen Seite der Grenze im Dreiländereck, wo Ungarn, Österreich und die Tschechoslowakei zusammenstießen.

Ich selbst bin in Wien geboren, aber zu der Zeit gehörte Österreich zu den Gebieten, die Hitler annektierte, um die Deutschen in den östlichen Ländern „heim ins Reich“ zu holen. Meine Tante Anni in Wien erzählte mir einmal, ich sei in einem jüdischen Sanatorium in Döbling geboren. Bei meinen Internetforschungen stieß ich auf Geheimakten, die mir keinen Zugang boten. Darum pilgerte ich vor fünf Jahren nach Döbling, dem ältesten Stadtteil von Wien im 19. Bezirk. Dort hat Jan III. Sobieski 1683 die Osmanen unter dem Großwesir Kara Mustafa Pascha in der Schlacht von Wien auf dem Kahlenberg besiegt[11] und damit das christliche Abendland gerettet. Ich wollte sehen, wo ich das Licht der Welt zum ersten Mal erblickte. Das Grundstück, vor dem ich stand, war leer, das Haus wahrscheinlich im Krieg zerstört oder später abgerissen. Ich dachte, es sei möglich, dass das geheimnisumwitterte verschwundene Sanatorium eine große Villa war, wie die Gebäude links und rechts von dem leeren Fleck. Vielleicht existierte die Villa aber noch, und ich war auf meiner Suche nur daran vorbei gegangen, denn vielleicht hatte man mit der Zeit die Hausnummern geändert, wie das so oft bei der Modernisierung vorkommt.

Vor ein paar Wochen fiel mir aber meine Geburtsurkunde wieder in die Hände, und ich stellte fest, dass ich mich in der Hausnummer geirrt hatte, als ich 2015 in Wien war. Es stellte sich heraus, dass mein Geburtshaus das ehemalige Sanatorium der Wiener Kaufmannschaft war, das 1912 auf demselben Grundstück der 1909 errichteten Privatkrankenanstalt des Wiener Handelsstandes gebaut wurde.[12] Heute ist es das Wilhelm-Exner-Haus der Wiener Universität für Bodenkultur und steht zusammen mit dem sezessionistischen Verwalterhaus, das 1909 von dem Architekten Ernst Gotthilf errichtet wurde, unter Denkmalschutz.[13] Jetzt dient die Gotthilf-Villa als Zentrum für Internationale Beziehungen der BOKU. 1939 kam das Sanatorium in den Besitz der Stadt Wien, die es an die deutsche Luftwaffe verpachtete.

Wilhelm-Exner-Haus © Wikipedia Wilhelm-Exner-Haus © Wikipedia |

Als ich dort geboren wurde, muss es als Lazarett gedient haben. Mein Vater war Unteroffizier der Luftwaffe, in Langenlebarn stationiert, wo er mit meiner Mutter lebte. Sie erzählte einmal, dass ich auch im Zug zwischen Langenlebarn und Wien hätte geboren werden können, denn sie war hochschwanger, als sie sich mit der Bahn zu diesem Lazarett begab. Es ist möglich, dass mein Vater sich dort aufhielt, weil er im Krieg von einem Granatsplitter am Nacken verletzt worden war.

Meine Großeltern – die Eltern meiner Mutter – im Habsburgerreich vor der Jahrhundertwende geboren, lebten im östlichsten Winkel vom Burgenland, ganz nah am Eisernen Vorhang an der ungarisch-tschechischen Grenze. Bei einem Besuch in den Sommerferien, als ich klein war, hörte ich die Erwachsenen vom Eisernen Vorhang sprechen. Ich dachte, es wäre ein richtiger Vorhang aus Eisen, konnte mir aber nicht vorstellen, wie so etwas in Wirklichkeit aussah. Mein Großvater brachte mich mit meinem Vater auf die Felder an der Grenze von Ungarn, um mir den dreireihigen Stacheldrahtzaun zu zeigen, hinter dem es einen hundert Meter breiten Streifen von Minenfeldern im Niemandsland gab und dann noch einmal dreifache Reihen von Stacheldraht. In regelmäßigen Abständen gab es Wachttürme mit bewaffneten Soldaten besetzt, die schussbereit eine Überquerung der Grenze ins Burgenland verhinderten. Von der Oberen Hauptstraße im Dorf konnte man von weitem auf der anderen Seite des Eisernen Vorhangs in der Tschechoslowakei (der heutigen Slowakei), etwa fünf Kilometer im Vogelflug entfernt, die Burg von Bratislava sehen, wo eine Schwester meiner Großmutter lebte, mit der sie sich ihr Leben lang nicht mehr treffen konnte, weil meine Oma starb, bevor sich der Eiserne Vorhang wieder öffnete.

|

|

Dieser Durchbruch des Stacheldrahts war dem 1988 neu ernannten ungarischen Ministerpräsidenten Miklós Németh[14] zu verdanken, der diese Grenze auf Grund internationaler und moralischer Gesetze abreißen ließ. In Fertörákos, nicht weit von Sopron, nur eine Stunde mit dem Auto vom Dorf meiner Großeltern entfernt, wurden im August 1989 die ersten Fluchtversuche von vier DDR-Bürgern mit Hilfe eines ungarischen Grenzpolizeikommandanten gemacht, der die Fliehenden zwar festnahm, ihnen dann aber bei ihrer Freilassung flüsternd verriet, dass sie unbehindert durch den unbewachten Wald über die Grenze ins Burgenland fliehen könnten. Auf eigene Verantwortung verhaftete er weitere 10.000 Flüchtlinge und ließ sie ohne Anweisung aus Budapest wieder frei.[15] Schon im März 1989 hatte Miklós Németh sein Vorhaben, den Eisernen Vorhang nach den ersten freien Wahlen abzubauen, mit Michail Gorbatschow, dem Generalsekretär der Kommunistischen Partei der Sowjetunion in Moskau besprochen, um zu prüfen, wie ernst er es mit seiner Idee von Perestroika, der politischen und wirtschaftlichen Reformen und Umstrukturierung innerhalb des kommunistischen Systems, meinte. Weil Gorbatschow keine Anstalten machte, ihn an seinem Plan zu hindern, ließ Németh im Mai 1989 die Presse zu einem Fototermin an die Grenze bei Hegyeshalom kommen, wo der Abbau des Eisernen Vorhangs begann. Nachträglich durchschnitt Gyula Horn, der letzte kommunistische Außenminister Ungarns, zusammen mit dem österreichischen Außenminister Alois Mock am 27. Juni 1989 symbolisch den Eisernen Vorhang für die Medien.[16] Deshalb wohl wurde Horn statt Németh die Öffnung der Grenze zugeschrieben.

Walpurga von Habsburg, Dame des Malteserordens und Tochter Otto von Habsburgs, organisierte im August 1989 das Paneuropäische Picknick im ungarischen Sopron,[17] bei dem ein Grenztor für drei Stunden symbolisch geöffnet werden sollte. Zwischen 600 und 700 DDR-Bürger, die zu Besuch an den Balaton nach Ungarn gekommen waren, flohen bei dieser Gelegenheit ins Burgenland. Als Staatsminister und Parlamentsmitglied unterstützte Imre Pozsgay[18] diese Aktion, indem er den ungarischen Oberbefehlshaber der Grenzpolizei benachrichtigte, und ihn bat, nicht einzugreifen, wenn die Flüchtlinge den Weg in die Freiheit suchten.

Dem Durchbruch des Eisernen Vorhangs bei dem Picknick in Sopron im August folgten im November 1989 die Demonstrationen in Leipzig und der Mauerfall in Berlin, was Gorbatschow nicht verhinderte, weil er „der Geschichte ihren Lauf lassen“ wollte. Wie eine Leipziger Demonstrantin nach dem Fall der Mauer bemerkte, wäre ohnehin alles so gekommen: „Ich will die Tatsache, dass wir ʻ89 auf die Straße gegangen sind, nicht etwa klein machen. Es gehörte damals wirklich Zivilcourage dazu, und es ist das in meinem Leben, worauf ich wirklich stolz bin, aber es [das System] wäre auch ohne den Herbst ʻ89 zugrunde gegangen“[19], meinte sie, und damit hatte sie Recht. Durch dieses „Loch“ an der Grenze zwischen Ungarn und Österreich entflohen 50.000 DDR-Bürger aus Budapest und der Prager Botschaft in das Burgenland und die Freiheit im Westen. Sie ließen ihre Trabis, Campers und persönlichen Besitz einfach in Ungarn liegen und stehen und begaben sich zu Fuß, erst zu zweit, dann zu viert, dann in immer größeren Gruppen zur Grenze hin, wo zuerst ein paar Leute von den Grenzwächtern angeschossen wurden, schließlich aber fast alle glücklich über die Grenze kamen. Nur ein junger Vater wurde bei der Flucht tödlich verletzt, schob aber mit letzter Anstrengung noch sein Baby auf die andere Seite des Eisernen Vorhangs in die Sicherheit.

Früher hatte ich mir gewünscht, dass die Grenze zu Ungarn und der damaligen Tschechoslowakei sich einmal öffnen würde, dass das Dorf meiner Großeltern nicht mehr am Ende der Welt liegen würde, weil man an der Grenze nicht weiter konnte. Ich hatte gehofft, dass man mit dem Auto oder der Bahn hinüberfahren könnte und die von „drüben“ zu uns kommen könnten, dass es einen regen Verkehr zwischen den getrennten Ländern geben würde. Niemand hatte aber einen so großen Zustrom von Flüchtlingen aus dem Osten erwartet, auch nach der Demokratisierung der kommunistischen Länder, die friedlich in der Tschechoslowakei und Ungarn verlief, aber ein Blutbad in Rumänien verursachte. Als ich nach dem Fall der Grenzen mit einem Onkel und einer Tante aus Wien, die das Haus meiner Großeltern geerbt hatten, auf ein paar Wochen Urlaub ins Burgenland fuhr, war das Dorf voll von uniformierten Soldaten, die beauftragt waren, illegale Einwanderer aus den östlichen Ländern festzunehmen. Die Wachtposten an der Grenze waren wieder besetzt, aber diesmal nicht von ungarischen Grenzsoldaten, sondern von Soldaten des österreichischen Bundesheers, die für Sicherheit am Ort zu sorgen hatten und wie eine einheimische Besatzung durch die Dorfstraßen marschierten.

Nach dem Fall des Eisernen Vorhangs fuhr ich einmal mit einer Bekannten im Auto hinüber auf die Burg von Bratislava, nur um von einem Café aus von dort oben auf ein paar Stunden den Blick auf die barocke Altstadt und die Donau zu genießen. Schon beim Geldumtausch war die Sprache auf der tschechischen Seite problematisch, denn niemand sprach Deutsch oder Englisch. Verwandte aus Bratislava, von denen ich nichts wusste, kamen nach der Öffnung der Grenze zu Besuch zu meinem Onkel und meiner Tante im Burgenland und in Wien. Das war ein Neffe meiner Mutter und meiner Tanten mit seiner Tochter Gabi, die damals vierzehn war. Gabi sprach Slowakisch und Deutsch, mein Onkel Deutsch und Dänisch. Nur meine Tante konnte sich auf Ungarisch mit Gabis Vater verständigen, denn sie hatte es als Kind in der Klosterschule in Mosonmagyaróvár gelernt. Bratislava, heute die Hauptstadt der Slowakei, hieß früher Pozsony und war im Habsburgerreich von 1536 bis 1783 die Haupt- und Krönungsstadt Ungarns.[20] Auf deutsch ist die Stadt als Preßburg bekannt. Die Geschichte von Bratislava und meinen Verwandten dort erinnert mich an eine Bemerkung von Ilse Tielsch, deren Vorfahren im Grenzland zwischen Böhmen und Mähren im Habsburgerreich lebten. In ihrem Buch Die Ahnenpyramide schreibt sie, dass man ohne die eigene Wohnung zu verlassen, das Haus, in dem diese Wohnung ist, oder den Ort in dem man lebt, ein Bürger von Österreich sein kann, dann von der Tschechoslowakei, dann Deutschland, und schließlich staatenlos: „überhaupt kein Staatsbürger mehr…“[21]. Sie musste am Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs aus ihrer südmährischen Heimat fliehen. Meine ungarischen Verwandten in der Slowakei sind nicht ausgewiesen worden. Sie haben sich adaptiert und, als die Tschechen nach dem Krieg an die Regierung kamen, in der Öffentlichkeit statt Deutsch nur Slowakisch gesprochen und zu Hause ganz geheim nur Ungarisch, wie Tante Irma mir erzählte, die 89 war, als ich sie 2015 zum ersten Mal traf. Sie ist die Schwiegertochter der Schwester meiner Großmutter, von der meine Oma zu mir als Kind sprach. Von ihr erfuhr ich, dass meine Großtante Katarina hieß und eine große Leseratte war. Als ich mit Gabi zu Besuch nach Rusovce kam, hörte Tante Irma mich Deutsch mit ihr sprechen, und ihre Augen leuchteten auf. Sie erklärte mir den ganzen Familienstammbaum auf Deutsch, und ich schrieb mit. Viele Jahrzehnte hatte sie kein Deutsch gesprochen, und ihre drei Söhne, die ungefähr in meinem Alter waren, wussten nicht, dass sie es konnte. Bei anderen Verwandten, die wir antrafen, musste Gabi vermitteln, weil sie Slowakisch sprach. Die dritte Sprache der Verständigung wäre Ungarisch gewesen, aber das hatte sie nicht gelernt, obwohl ihr Vater damit aufgewachsen war. In der Schule war Russisch für sie ein Pflichtfach.

***

Das burgartige Internationale Haus in Berkeley auf dem Campus der Universität von Kalifornien, wo ich drei Jahre und viele Sommer lang wohnte, wurde zwischen den beiden Weltkriegen (1930) von John D. Rockefeller Jr. gegründet, um das Verständnis zwischen Studenten und Forschern aus allen Ländern der Welt zu fördern. Als Studentenwohnheim bietet es eine multikulturelle Erfahrung und macht es sich zum Ziel, eine friedlichere, tolerantere Welt zu schaffen. Dabei spielen die Gespräche bei Tisch im gemeinsamen Speisesaal eine große Rolle und die monatlichen Sunday Suppers, bei denen kulturelle Programme von den internationalen Studenten geboten werden. Ohne weit zu reisen, kann man Vertreter aus aller Welt in der Großen Halle oder im Café treffen und die neuesten Nachrichten mit ihnen besprechen, mit Griechen und Zyprioten, mit Palästinensern und Israeliten, mit Indern, Persern, Arabern und Chinesen, Japanern, Türken, Deutschen, Franzosen, Belgiern und Holländern, mit Studenten und Forschern aus der Schweiz und Italien, aus Nord- und Südamerika, Kanada und Afrika. Ungefähr 600 Studenten aus 75 Ländern leben „unter dem Dom“, dem orientalisch anmutenden gewölbten Turm und Kennzeichen des Baus. Manche Zimmer über dem Eingang haben einen großzügigen Blick auf die Bucht von San Francisco und die Golden-Gate-Brücke. Der venezianisch wirkende Campanile, Wahrzeichen der Universität, ragt unterhalb von Piedmont Avenue wie ein säkulares Minarett mit dem Ruf zum Wissen und zur Erkenntnis mehr als 100 Meter hoch über dem Campus auf: „Fiat Lux!“

© Wikipedia: Internationales Haus in Berkeley mit dem Campanile der Universität |

Als ich Mitte der sechziger Jahre nach Berkeley kam, wollte ich eigentlich Komparatistik studieren und tat das auch zwei Semester lang. Mein Studienberater und Professor für Mittelhochdeutsch, das mich begeisterte, überzeugte mich jedoch, der Germanistik den Vorrang zu geben und bot mir eine Assistentenstelle an. Damit begann die Suche nach meiner Vergangenheit anhand der deutschen Literatur. Ich kann mich noch deutlich daran erinnern, dass ich bei meinem Amtsantritt ein Dokument in einem Büro in Sproul Hall unterzeichnen musste, in dem ich schwor, dass ich die Verfassung der Vereinigten Staaten und die Verfassung des Staates von Kalifornien unterstützen und meine Pflichten getreu und nach bestem Wissen und Gewissen erfüllen wolle. Außerdem musste ich bestätigen, dass ich kein Mitglied der Kommunistischen Partei sei oder irgendeiner Organisation angehöre, die den Umsturz der Regierung durch Macht oder Gewalt befürwortete; dass ich keinen Konflikt hätte mit der Ausführung meiner Pflichten, was unparteiische wissenschaftliche Forschung und das Streben nach Wahrheit beträfe. Diese Aussage war eine Bedingung für meine Anstellung und die Erwägung meines Gehalts. So lautet der Text von 1950, den ich im Archiv fand. Es ist möglich, dass er in den sechziger Jahren etwas verändert wurde. Später erinnerte ich mich nur daran, dass ich keinen Umgang mit Kommunisten haben sollte.[22]

So manifestierte sich der Kalte Krieg weit entfernt vom Eisernen Vorhang und der Mauer in Berlin auch im sonnigen Kalifornien. Umso erstaunlicher ist es, dass drei Jahre später schon die ersten Studenten und Wissenschaftler aus Rumänien an der Universität in Berkeley und im Internationalen Haus zugelassen wurden. Jetzt weiß ich, dass das auf Ceauşescus Annäherungsversuchen an den Westen beruhte.[23] Als neuer Generalsekretär der Kommunistischen Partei ab 1965 machte er sich in Rumänien und im Westen beliebt, weil er eine Außenpolitik einführte, die der Sowjetunion entgegenstand. Er weigerte sich 1968, mit den Sowjets in der Tschechoslowakei einzumarschieren, obwohl sein Land Mitglied im Warschauer Pakt war. In der Woche vor der Unterdrückung der Revolution mit Panzern reiste er selbst nach Prag, um Alexander Dubček moralisch zu unterstützen. Dadurch wurde er zum Ausnahmefall im kommunistischen Ostblock. Bei offiziellen Besuchen im Westen – in den Vereinigten Staaten, Großbritannien, Frankreich, Spanien und Australien – gab er sich als Reform-Kommunist aus, um internationalen Respekt für Rumänien zu gewinnen. Als Mittelmann in internationalen Konflikten verhandelte er mit den Gegnern und half dem neugewählten US-Präsidenten Richard Nixon 1969 bei der Eröffnung von diplomatischen Beziehungen zum kommunistischen China. Wegen der Liberalisierung der beiden neuen Regierungen kam es wohl zu dieser Zeit, dass rumänische Studenten und Wissenschaftler ihr Land verlassen und im Westen studieren durften.

Doch wie schon Goethe in seinem Faust bemerkt: „Grau, teurer Freund, ist alle Theorie und grün des Lebens goldner Baum.“ Nicolae Ceauşescu wurde zum Diktator in Rumänien, und die Universität von Kalifornien in Berkeley zog ihre Grenzen bei der Praxis von sozialistischen Idealen. Auf einem verlotterten Grundstück in der Haste Street, einen Block oberhalb von Telegraph Avenue, in dessen Besitz die Universität zwei Jahre vorher durch Enteignung der Hausbesitzer gekommen war, deren Häuser abgerissen wurden, säten Hippies im Frühjahr 1969 Rasen an für einen von der Stadt- und Universitätsverwaltung bewilligten People’s Park.[24] Sie stellten Schaukeln und Rutschen für die Kinder auf und pflanzten Blumen an, um den Block zu verschönern und allgemein brauchbar und friedlich nutzbar zu machen. Als die Universität das Grundstück zurückforderte, um einen Parkplatz darauf zu bauen, kam es zu einem brutalen Konflikt zwischen den konservativen und liberalen Mächten in Berkeley, unterstützt von dem damaligen Gouverneur Ronald Reagan, der die Nationalgarde gegen die „Blumenkinder“ aufrief, um die Polizeiaktion zu stärken. Viele der Soldaten waren gerade aus Vietnam zurückgekehrt und behandelten die Hippies wie Feinde im Krieg.[25] Sie wurden von Bajonetten bedroht, und ein Student, James Rector, wurde von der Polizei erschossen.[26] Panzer rollten auf der Südseite vom Campus hinunter. Soldaten mit Schutzhelmen und Gewehren standen an allen Eingängen zur Universität. Polizeiautos verfolgten Studenten auf den Straßen mit Tränengas, auch wenn sie an der ganzen Situation nicht beteiligt waren. Das Tränengas, das ein Hubschrauber über dem Campus versprühte, drang in alle Klassenzimmer ein und gefährdete Patienten im Universitätskrankenhaus, auch in der Eisernen Lunge. Ich hatte gerade ein Seminar in Dwinelle Hall und lief in das unterste Stockwerk, wo ich mich sicherer glaubte, aber das Tränengas füllte das ganze Gebäude. Ich machte ein Taschentuch am Wasserhahn nass, hielt es über die Nase und versuchte, so schnell wie möglich den Block bis zum Internationalen Haus hinaufzulaufen, konnte den Kanistern aber nicht entgehen, die von der Polizei auf Fußgänger entlang des Bancroft Way geworfen wurden. Es gab eine militärische Sperrstunde, und zwischen Studenten und der Polizei herrschte ein Kriegszustand, denn im Prinzip ging es um einen ideologischen Kampf zwischen den kapitalistischen Besitzrechten der Uni und den sozialistischen und humanistischen Werten der Hippies und Studenten. Aus dem umstrittenen Grundstück wurde ein zementierter Parkplatz, auf den ich 1976 stieß, als ich von einer temporären Lehrstelle and der Universität von Illinois in Chicago zurückkam, um meinen Doktorvater zu wechseln und in Berkeley weiter an meiner Dissertation zu schreiben.

Wie magnetisch zogen mich die Studenten und Wissenschaftler aus den Ländern hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang an, die plötzlich nach dem Ende des Krieges in Vietnam ungefähr Mitte der siebziger Jahre im Internationalen Haus auftauchten: aus Polen, Russland, Jugoslawien und der damaligen Tschechoslowakei, mit Namen wie Milan, Bedřich, Janusz und Igor, die zum ersten Mal im freien Westen forschen und studieren durften. Das war lange vor Michail Gorbatschows Glasnost und Perestroika. Igor, Physiker an der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Prag, erklärte mir bei Tisch im Speisesaal scherzhaft die Ideale des Kommunismus: „Was mir gehört, gehört mir, und was dir gehört, gehört auch mir.“ Mit Janusz aus Polen, Igor und einem Russen, mit dem beide befreundet waren, machte ich einen Ausflug in die kalifornische Geisterstadt Columbia aus den Goldgräbertagen in der Gegend nördlich von Sonora.[27] Sie wurde 1850 gegründet und, in ihrem ursprünglichen Zustand erhalten, wirkt sie wie die Filmkulisse für einen Western. Hier kann man die Goldrauschzeit nachvollziehen und sich sogar im Goldwaschen üben. Highway 49, der sich auf eine Höhe von mehr als 2.000 Fuß nach Columbia hinaufschlängelt, wurde nach den Neunundvierzigern benannt, die zuerst nach Gold in Kalifornien suchten, kurz nachdem das Land in dem Vertrag mit Mexiko 1848 an die Vereinigten Staaten überging.[28] Ich zeigte ihnen auch Yosemite Park mit dem imposanten Halbdom aus Granit und dem Bridal-Veil-Wasserfall. Sie waren überrascht von einem Schild am Eingang, das uns informierte, dass es im Park Bären gäbe und man vorsichtig sein müsse beim Zelten und Wandern. Wir kampierten aber in einem Holzbau, der uns Sicherheit bot. Obwohl die Autotüren meines Ford Falcon nach einem schweren Unfall im November klemmten, fuhr ich mit Igor und Janusz im Dezember doch noch nach San Francisco, wo wir uns im Opernhaus kurz vor Weihnachten den „Nussknacker“ von Tschaikowski ansahen. Ein paar Wochen später musste ich Berkeley verlassen, um Anfang Februar eine Stelle am Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, anzutreten.

Im Rückblick musste ich mich fragen, warum gerade 1976 plötzlich Forscher aus Russland, Polen und der Tschechoslowakei ins Internationale Haus kamen. Igor konnte mir das nicht so genau sagen, als ich ihm vor Kurzem zu diesem Thema schrieb. Er berief sich nur auf das Austauschprogramm der Prager Akademie der Wissenschaften, bei dem er sich bewarb. Ihm wurde erlaubt, weniger als ein Jahr in Berkeley zu verbringen. Ich wunderte mich, was in der Weltpolitik zu diesem Zeitpunkt vor sich ging, um das möglich zu machen: Obwohl der Prager Frühling 1968 von den Sowjets durch den Einmarsch von einer halben Million Soldaten des Warschauer Paktes brutal unterdrückt wurde und Panzer den Forderungen der Demonstranten nach politischer Liberalisierung und Demokratisierung unter Alexander Dubček ein Ende bereiteten,[29] gab es in den nächsten zwei Jahrzehnten trotz aller Gefahren der Verfolgung und Inhaftierung unter der streng kommunistischen Regierung seines Nachfolgers Gustáv Husák doch weiterhin Versuche von Einzelnen und von Gruppen, Reformen durchzuführen. Schon 1966 hatte die Tschechoslowakei auf einer Sicherheitskonferenz einen Pakt der Vereinten Nationen für soziale, wirtschaftliche und kulturelle Rechte unterzeichnet, sowie einen Pakt für bürgerliche und politische Rechte, die beide 1975 ratifiziert wurden und im März 1976 in Kraft traten.[30] Zusätzlich garantierte die Helsinki-Schlussakte von 1975, die von der Sowjetunion, Polen und der Tschechoslowakei unterschrieben wurde, spezifische Menschenrechte und die Kooperation im Handel und in der wissenschaftlichen Zusammenarbeit zwischen diesen Ländern und dem Westen.[31] Ähnlich wie das Buchmobil der Amerikaner nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg im Süden Deutschlands eine „kulturelle Diplomatie“ ausübte, so baute man schon vor Gorbatschows Glasnost und dem Fall des Eisernen Vorhangs durch die Helsinki-Schlussakte eine „wissenschaftliche Diplomatie“ über Kontakte zwischen Forschern aus Amerika und Osteuropa auf. So kam es, dass der Kollege aus Russland, Janusz aus Polen und Igor aus der Tschechoslowakei die Möglichkeit wahrnehmen konnten, schon vor dem Fall des Eisernen Vorhangs ihre Forschung auf den Gebieten der Wirtschaft und der Physik in Kalifornien zu betreiben.

***

Wie ein Mosaik fügen sich die Steinchen der Vergangenheit zusammen im Rahmen der Weltpolitik, wenn auch Lücken und Rätsel bestehen bleiben. Meine Familiengeschichte ist eng verflochten mit der Geschichte Europas durch die Orte, wo ich meiner Herkunft nach verankert bin: Stettin, Berlin, Bratislava, Mosonmagyaróvár, Wien. Meine Wurzeln reichen von der Ostsee bis zum Neusiedler See, dem „Meer der Wiener“, von der ehemaligen Mark Brandenburg bis zum Flachland im Burgenland, der Slowakei und Ungarn.

Das Haus, in dem ich jetzt lebe, ist nicht weit von Poughkeepsie – dem Wohnort von Henry Morgenthau Jr. – und Hyde Park, wo Franklin Delano Roosevelt sein Landgut hatte, das jetzt ein Museum ist. Ich wohne auf der anderen Seite vom Hudson River, der Dutchess County von Ulster County trennt. Mein Vater hat unser Haus vor 60 Jahren selbst gebaut, und es ist das Vermächtnis meiner Eltern, deren Gegenwart ich hier spüre. Während meiner Wanderjahre in Amerika von der Ostküste an die Westküste, von Lake Michigan bis zum Golf von Mexiko in temporären Lehrstellen vor Beendung meiner Dissertation, bin ich in den Ferien immer wieder in mein Elternhaus zurückgekehrt, auch aus dem Mittleren Westen, nachdem ich meine feste Anstellung an der Universität von Minnesota erhielt und viel zu Konferenzen und Lesungen reiste. Es war der feste Punkt, der Anker in meinem Leben. Die ältere Generation in meiner Familie lebt nicht mehr. Wien war mein zweites Zuhause, aber seit dem Tod meiner Onkel und Tanten bin ich dort obdachlos geworden. Ein Nachbar meiner Großeltern hat das Haus im Burgenland übernommen und es liebevoll im Burgenländer Stil restauriert. Die einzige Verwandte, die mit mir in Verbindung bleibt, ist meine Kusine Gabi, die hinter dem Eisernen Vorhang geboren und im sozialistischen System in der Slowakei aufgewachsen ist. Ihr Vater war Aufseher in einer Landwirtschaftlichen Produktionsgenossenschaft, immer auf Abruf bereit, wie sie mir erzählte. Er war ein paar Jahre jünger als ich, starb aber schon in seinen Vierzigern, sieben Jahre nach dem Fall des Eisernen Vorhangs. Ich habe ihn nicht gekannt. Mit Gabi und ihrer Schwester Erika besuchte ich sein Grab bei meinem Besuch in Rusovce, in der Nähe von Bratislava. Vor zwei Jahren hat Gabi mir ein gerahmtes Bild zu Weihnachten geschickt, das ihre ganze Familie zeigt, die ich erst vor einigen Jahren zum ersten Mal getroffen habe: ihre Mutter, ihre Schwester und ihren Bruder, ihre Nichten und Neffen in der Slowakei, ihren Mann und ihre zwei kleinen Kinder aus Österreich, wo sie jetzt lebt. Sie hat das Foto digital bearbeiten und mich in die Gruppe hineinfügen lassen, um mir zu zeigen, dass ich nicht alleine bin, dass ich zu ihrer Familie gehöre, zu den Nachkommen der Schwester meiner Großmutter aus dem Burgenland.

Footnotes:

[1] „Der Morgenthau-Plan – eine Idee mit Sprengkraft: Wie Deutschland fast zum Bauernstaat wurde.“ Politik. Süddeutsche Zeitung. 21. September 2019. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/morgenthau-plan-1.4609175 (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021).

[2] „Churchill’s Iron Curtain Speech.“ Westminster College. Fulton, Missouri. March 5, 1946. https://www.wcmo.edu/about/history/iron-curtain-speech.html (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021).

[3] „Potsdamer Abkommen. Zwangsumsiedlungen und Vertreibungen.“ https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potsdamer_Abkommen (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021). Dazu auch Gregor Delvaux de Fenffe. „Flüchtlingsströme. Fluchtbewegungen.“ https://www.planetwissen.de/geschichte/deutsche_geschichte/flucht_und_vertreibung/fluechtlingsstroeme-106.html (eingesehen am 28. Januar 2021).

[4] Borchardt, Edith. „Visions of a United Europe: Novalis, Eméric Crucé, Victor Hugo, and Rudolf von Habsburg.“ In: Schatzkammer der deutschen Sprache, Dichtung und Geschichte 27 (2001), S. 149-156. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/german/6/ (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021).

[5] Hamann, Brigitte. Rudolf. Kronprinz und Rebell. München 1978. S. 13.

[6] „Otto von Habsburg.“ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Otto_von_Habsburg (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021).

[7] …unbesetzter Stuhl: Siehe Par. 4.

[8] Picknick von Sopron: „Pan-European Picnic.“ 19. August 1989 – a step on the way to German reunification. https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/news/-pan-european-picnic–1662402 (eingesehen am 29. Januar 2021).

[9] „The idea of opening the border at a ceremony came from Otto von Habsburg and was brought up by him to Miklós Németh, the then Hungarian Prime Minister, who also promoted the idea.“ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan-European_Picnic – cite_note-4 Par. 2. (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021).

[10] „Vertrag von Trianon.“ Austria-Forum. https://austria-forum.org/af/AustriaWiki/Vertrag_von_Trianon

(eingesehen am 29. 1. 2021) und „Venediger Protokolle.“ https://www.rechteasy.at/wiki/venediger-protokolle/ (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[11] „Schlacht am Kahlenberg.“ Ende der Zweiten Wiener Türkenbelagerung 1683. Martinovsky, Dominik. Die Schlacht am Kahlenberg als Wendepunkt in der Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches. Diplomarbeit. University of Vienna: Historisch-Kulturwissenschaftliche Fakultät, 2016.

[12] Sanatorium der Wiener Kaufmannschaft, Privatkrankenanstalt des Wiener Handelsstandes (Auktions-Ansichtskarte): https://www.ansichtskarten-center.de/doebling/wien-1925-doebling-sanatorium-krankenhaus-preissenkung (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[13] Wilhelm-Exner-Haus: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:D%C3%B6bling_-_Wilhelm-Exner-Haus.JPG (eingesehen am 23. Januar 2021).

[14] Miklós Németh is a Hungarian economist and politician, who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 24 November 1988 to 23 May 1990. Géza Entz. “Miklós Németh. The Premier of a Peaceful Transition 1988-1990.” Hungarian Review.” 16. Juli 2015. http://www.hungarianreview.com/article/20150716_miklos_nemeth_the_premier_of_peaceful_transition_1988_1990 (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[15] Die Große Freiheit, Teil 1: Der Traum von Budapest. Ein Film von Friedrich Kurz und Guido Knopp. Buch und Regie: Friedrich Kurz, ZDF 1994. https://www.new-video.de/film-guido-knopp-die-grosse-freiheit/ (eingesehen am 22. Januar 2021).

[16] „Vor 30 Jahren hat es an der österreichisch-ungarischen Grenze ein historisches Ereignis gegeben. Die Außenminister der beiden Länder, Alois Mock und Gyula Horn, haben den ‚Eisernen Vorhang’ durchschnitten. Es entstand ein Foto, das damals beigetragen hat, Europa zu verändern. 27. Juni 1989: Ein Foto verändert Europa.“ https://noe.orf.at/stories/3002107/ (eingesehen am 23. Januar 2021).

[17] Zum Picknick von Sopron: „Walpurga Habsburg Douglas: ‘We knew the Iron Curtain could fall.’“ https://www.dw.com/en/walburga-habsburg-douglas-we-knew-the-iron-curtain-could-fall/a-17863605 (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[18] As the minister of culture (1976−80), minister of education (1980−82), minister of state (1988−90), and parliament member (1983−94), he [Pozsgay] was the only ranking member of the Communist Party to play an active role in the political events of the great time of regime change, 1988−90.” Maciej Siekierski. “In Memoriam Imre Pozsgay 1933-2016.” https://www.hoover.org/news/memoriam-imre-pozsgay-1933-2016 (eingesehen am 29. Januar 2021).

[19] Aus meinem persönlichen Transkript zu dem Film, Die Große Freiheit, Teil 3. Das Wunder von Berlin. Ein Film von Ekkehard Kuhn und Guido Knopp. Buch und Regie: Ekkehard Kuhn, ZDF 1994.

[20] „Pressburg (slowak. Bratislava), im äußersten Westen des historischen Königreiches Ungarn an der Donau gelegen (der ungarische Name der Stadt lautet Pozsony), übernahm von 1536 bis 1784 die Funktion als ungarische Haupt- und Krönungsstadt.“ https://www.habsburger.net/de/schauplaetze/pressburg?language=en (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[21] Borchardt, Edith. Review: The Ancestral Pyramid by Ilse Tielsch. Trans. David Scrase. Southern Humanities Review 37 no. 2 (2003) 195 – 198. Originalausgabe: Ilse Tielsch, Die Ahnenpyramide. Graz: Verlag Styria, 1980. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=german (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[22] Loyalty Oath, University of California, Berkeley, during the McCarthy Era:

https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/uchistory/archives_exhibits/loyaltyoath/symposium/oath.html (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[23] „Nicolae Ceauşescu.“ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicolae_Ceau%C8%99escu

(eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[24] „People’s Park“ (Berkeley). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People%27s_Park_(Berkeley)

(eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[25] „Bloody Thursday“, 15 May 1969, „was the day the Vietnam war came home. The streets of Bohemian Berkeley, the New Left’s west coast HQ, became a bloody war zone. Martial law was declared, a curfew imposed and national guardsmen with unsheathed bayonets and live ammunition occupied the town. A military helicopter doused the campus with tear gas. Many members of the Alameda county sheriff’s department had just come home from Vietnam. Some later admitted that they treated antiwar students like Viet Cong.“ https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/jul/06/the-battle-for-peoples-park-berkeley-1969-review-vietnam (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[26] James Rector was shot on „Bloody Thursday“ in Berkeley, May 15, 1969:

https://datebook.sfchronicle.com/books/newfound-photos-mark-50th-anniversary-of-the-day-peoples-park-turned-deadly (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[27] „Columbia, California 1850. Historic Gold Rush Town.“ http://visitcolumbiacalifornia.com/ (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[28] „In 1848, a treaty was signed between the U.S. and Mexico which allowed the U.S. to claim California as their own. However, it didn’t officially become a recognized state until September 9, 1850, and this was in part due to the California Gold Rush.“ https://www.luckypanner.com/history-of-california-gold-rush-and-the-forty-niners/ (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

[29] „50 Jahre Prager Frühling.“ https://www.bpb.de/politik/hintergrund-aktuell/167238/50-jahre-prager-fruehling (eingesehen am 29. Januar 2021).

[30] „In the context of international detente, Czechoslovakia had signed the United Nations Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1968. In 1975 these were ratified by the Federal Assembly, which, according to the Constitution of 1960, is the highest legislative organization. The Helsinki Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Final Act (also known as the Helsinki Accords), signed by Czechoslovakia in 1975, also included guarantees of human rights.“ https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-3&chapter=4&clang=_en

(eingesehen am 31. Januar 2021).

[31] „Helsinki Final Act, 1975.“ „The Soviet Union, Poland, and Czechoslovakia were among the nations who signed the Final Act of the Helsinki Accords. That promoted cooperation between the West and these countries, among others.“ https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/helsinki (eingesehen am 24. Januar 2021).

Comments Off on IV. Essays und autobiografische Texte: Heimatbilder, Grenzgebiete