Dec 23 2020

III. Kulturgeschichtliche Analysen: Kurt Weill: Connecting Continents and Cultures

Variations on a Theme:

The Reconstructed Jewish Identities

of Arnold Schoenberg and Kurt Weill

Part II: Kurt Weill: Connecting

Continents and Cultures

Michael Panitz, Norfolk, Virginia

Essay Abstract:

Concluding the analysis of the religious trajectories in the lives of two Central-European Jewish composers, Arnold Schoenberg and Kurt Weill, the previous installment having analyzed Schoenberg’s Judaism, this installment examines the Judaism of Kurt Weill. Like Schoenberg, Weill disengaged from Judaism as a young man and reconnected, to some degree, as a response to Nazi oppression. But in contrast to Schoenberg’s religiosity, Weill’s Judaism was mostly a matter of upholding the saga of the Jewish experience as presented in the Bible, embracing contemporary Jewish nationalism and collaborating with fellow artists on a range of anti-fascist and humanitarian causes consistent with Liberal Jewish values.

***

The stations of Kurt Weill’s life have often provided the skeleton for scholarly examinations of his artistic creativity. He was a “cross-over artist” in several senses. He crossed from the narrow cultural circle of modernist classical music to the broader circle of musical theater and cabaret productions. He also crossed continents, making his mark on the musical scene both in Europe and America. This essay explores the religious trajectory of his life. He crossed over from Judaism to religious indifference, and then back to selected Jewish commitments. His return was not to his starting point, however, a fact that helps us understand the range of options available for a person to express his Jewish identity in the open society of mid-20th century America.

The trajectory of Weill’s life resembled that of Schoenberg in its broad outlines.[1] Like his older contemporary, Weill left his childhood Judaism behind, emerged as a leading composer in Central Europe, expressed through his music his critique of the flaws in modern European life, became a prominent target of the Nazis, fled Hitler’s Germany, reengaged with Judaism and specifically with the stories of the Hebrew Bible, settled in the United States, and championed the Zionist cause.

But the important differences in the two men’s paths deserve mention and analysis. Weill’s Jewish background was much more comprehensive than Schoenberg’s. On the other hand, whereas Schoenberg studied the Bible throughout his life, Weill returned to the Bible as a source of inspiration after a decade of neglect, as part of his response to the rise of Nazism. Unlike Schoenberg, who converted to Christianity and then again to Judaism, Weill’s disengagement from, and reengagement with, Judaism were much less formal. Schoenberg manifested authoritarian tendencies, but the Jewish identity that Weill constructed in his final decade and a half of life was of a piece with the Jewishness espoused by the liberal majority of World-War II- era American Jewry. That identity foregrounded the Jewish commitment to social justice, rather than other aspects of the religion’s teachings. In such a construct, easily linking Jewish national aspirations with other humanitarian causes, Jews expressed their Jewishness, in large part, by helping others. (This remains true of Liberal Judaism today.)

The biblical parallel most fitting for Schoenberg was Moses. For Weill, in two senses, the apt parallel is to Aaron: First, Aaron was a spokesman; and second, Aaron was a connector.

When God encounters Moses at the Burning Bush, Moses is hesitant to accept the commission to confront Pharaoh and demand the liberation of the People Israel. Moses protests that he speaks haltingly. God responds that Aaron will be his mouthpiece: “There is your brother Aaron the Levite. He, I know, speaks readily… You shall speak to him and put the words in his mouth. …and he shall speak for you to the people. Thus, he shall serve as spokesman with you playing the role of God to him.” (Exodus 4:14-16)

Aaron-like, Weill made his mark in the world of music not as the individual creator, the solo composer of symphonies and other genres of absolute music—although he did produce such compositions in his first years of work. He abandoned that to focus on collaborative efforts. For most of his career, he composed music allied with words, movement and staging. His personal pathway of making art was collaborative.

Second, Aaron was not only the spokesman for Moses. He was also the priest, responsible for the ritual connection of God and the worshiping community of Israelites. For Weill, music risked becoming meaningless if it did not consciously seek to tend the connection between art and audience. In the post-traditional world of inter-war Europe and North America, that connection involved respecting the predilections of the real audience for his work. Collaboration and the turn to popular music were allied developments in Weill’s oeuvre.

The first product of his turn to a simplified, popular style was Der Protagonist, which premiered in March 1926. In the following year, he completed the Mahagonny Songspiel, (the term is a conscious departure from the German Singspiel, acknowledging an American idiom). This was to be the first of his collaborations with Bertolt Brecht. It received its premier at the Deutsches Kammermusikfest on July 17, 1927. Ten weeks later, he published what amounts to his artistic manifesto:

Today we’re nearing completion of a clear separation between those composers who, filled with disdain for the public, continue to work towards solution of aesthetic problems as if behind closed doors, and those who associate themselves with any audience whatsoever… because they realize that there is a general human consciousness beyond the artistic one which springs from a social awareness of some kind and that this must determine the formation of an artwork… In Germany it has been demonstrated very clearly that music must win a new justification for its existence… the socially exclusive arts, originating in a different era and from a different artistic attitude are losing more and more ground… Therefore, music is seeking an approach to a broader audience, because only then can it maintain its viability… Clarity of language, precision of expression, and simplicity of feeling… form the reliable aesthetic bases for a broader impact of this art.”[2]

In these respects, then, he was an “Aaron.” Others originated the words; Weill supplied the music that allowed those words to enter the limbic systems of the listeners and move them to a greater degree than words alone could accomplish.

The analogy is fruitful if it is not carried too far. Weill was no high priest of religion. He lived a predominantly secular life. But this part of the essay will explore the religious dimension of his life. As will be seen, while it was not the main current, it made its presence felt in the last decade and a half of his life.

Weill’s first published work was a Jewish wedding anthem. It was the work of a highly precocious thirteen-year-old. But that and the several other works of Jewish music he composed before leaving home are not more than a point of departure in a consideration of the trajectory of his religious development. They represent the world he left, first when he went to Berlin and joined the progressive artistic circles of the Weimar Republics, and then when he and Lotte Lenya, a Gentile woman, became life partners.

In the new freedom of Weimar Germany, Weill did not convert in order to marry the non-Jewish Lotte Lenya. Born a Christian, she was as remote from her religion of ancestry as he was. By the early twentieth century, Central Europe had become a more secularized society than it was in earlier generations, and couples originating in different faith communities could now build a life together.

At that time, intermarriage, no less than conversion away from Judaism, often meant the severing of family ties. In the traditional Jewish view, intermarriage was a death knell for the transmission of Judaism to future generations. In Weill’s case, his ties to family were not severed. But they were strained, and never healed fully; although, as will be shown, he did ultimately take steps in that direction, and specifically acknowledged the religious connection he had with his parents and with the Jewish people as the symbol of the work of healing.

Weill’s “Bibelsache”: Der Weg der Verheißung / “The Eternal Road”

“A long time after that, the king of Egypt died. The Israelites were groaning under their bondage and cried out; and their cry for help from the bondage rose up to God. God heard their moaning… God took notice of them.” (Exodus 2:23-25)

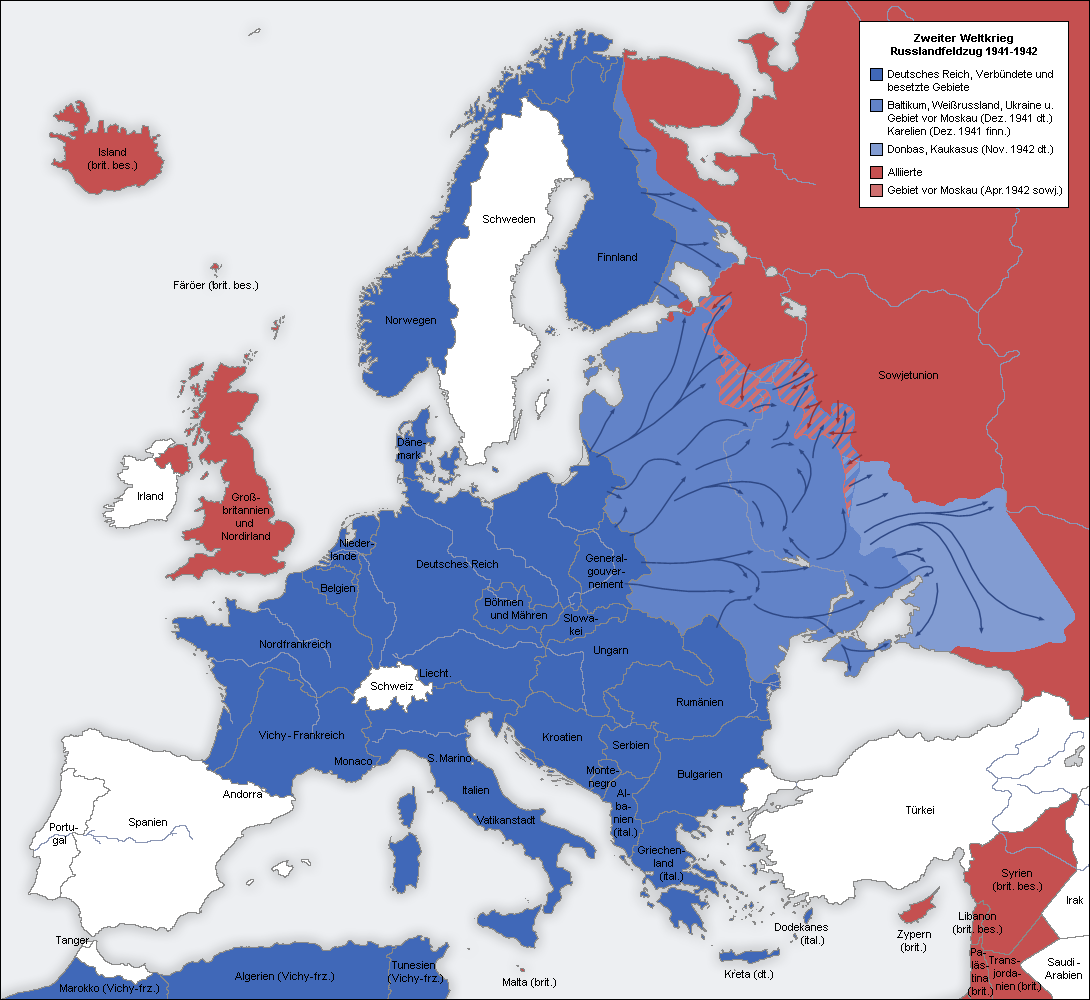

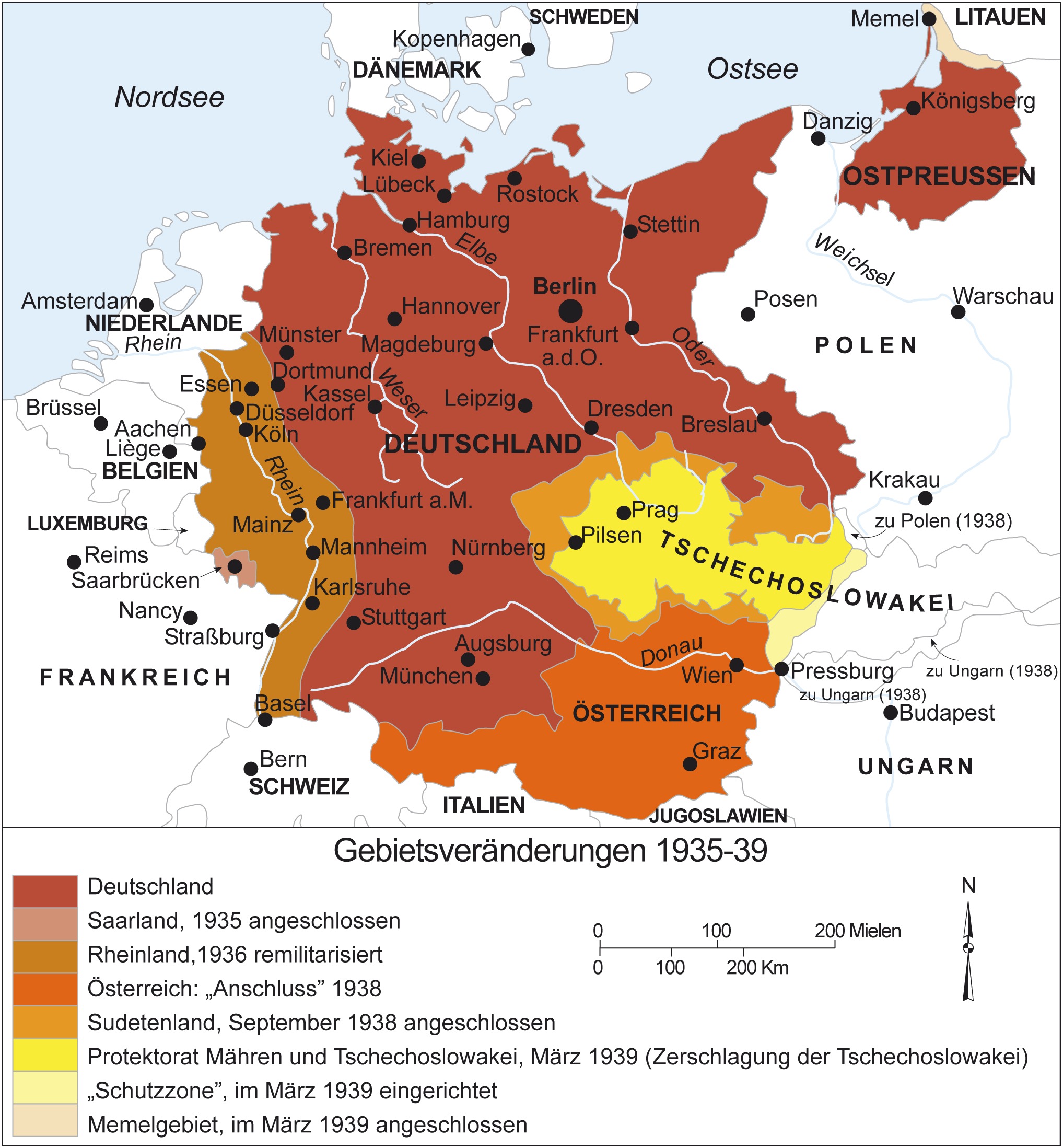

Weill did not quickly come to see his native land as a place of oppression. He was in many ways a true son of Weimar Germany—free to criticize, free to challenge boundaries, free to experiment. These qualities were prominently showcased in Weill’s most famous work, the music for Bertolt Brecht’s Dreigroschenoper (“Three-Penny Opera”), written in 1928. But with the demise of the Weimar Republic, his native land of broad vistas became an “Egypt,” a place of constriction. In Hebrew, the name for Egypt is “Mitsrayim,” which means “double narrow place.” After being his spiritual as well as geographical home for years, Germany became a very narrow place for Weill in 1933.

Weill’s period of active reengagement with the religion of his childhood began under the stimulus of Nazi persecution. Often attacked by the Nazis during their rise to power, with Nazi brown shirts disrupting performances of his pieces during the last two years of the Weimar Republic, Weill became a marked man as soon as Hitler took power in 1933. He fled Germany on March 21, 1933, just in time to avoid arrest.

Weill remained in Paris for nearly two years, until January 1935, and then in London for much of that year. During this period, he began his reconciliation with his then-estranged wife, Lotte Lenya. A private remark he made at that time to his student, the conductor Maurice Abravanel, sheds light on his sense of identity: “A good Jew always forgives his wife.”[3] With allowances for the irony that was often present in Weill’s off-hand remarks, the statement nonetheless attests to the endurance – and perhaps the resurgence—of his Jewish identity.

Even had he wished to leave his Judaism behind with his persecuted status upon leaving Germany, a dramatic confirmation of the presence of anti-Semitism in France made assimilation impossible. Weill enjoyed several successes in the Parisian musical world in the summer and autumn, but at a performance of his operatic allegory Der Silbersee on November 26, 1933, he was badly shaken by a demonstration. Amidst the bravos and applause, an established French composer and critic present in the audience, Florent Schmitt, led a group in shouting “Vive Hitler!” The public display of the anti-Semitism not only in Germany, but in France, as well, went a long way towards convincing Weill that France would be a waystation at best, not his Promised Land.[4]

If anti-Semitism was the push to leave France, there was also a pull to come to the United States. That was the prospect of an American staging of Der Weg der Verheißung (“The Road of Promise”), whose musical score Weill had largely completed in 1934. This project was the impetus for the decisive change in Weill’s life—from European to American and from a composer of both classic forms and Gebrauchsmusik in the European tradition to a major creative force in the world of Broadway musical theater. It was also the time of his most sustained reengagement with his Jewish heritage.

Der Weg der Verheißung was the brainchild of the Jewish-American impresario Meyer Weisgal. He envisioned the project as a musical response to the rise of Hitler. If today, in the light of the Holocaust and the tens of millions of other casualties during the Second World War, the thought that a stage show could be a response to Hitler seems naïve, it should be remembered that Weisgal’s idea dated to 1934, not long after the beginning of the Third Reich. He envisioned a large, dramatic piece in which the biblical heritage of Israel and the fortitude of the Jewish people during the long and tragic saga of their history could be lauded. Weisgal approached the theater director, Max Reinhardt, who, in turn, nominated Weill to write the music. The playwright Franz Werfel was their choice for the book.

In his 1971 autobiography, So Far, Weisgal described his meeting in May 1934 with Reinhardt, his associate Rudolf Kommer, Werfel and Weill, at which the artists agreed to collaborate on the biblical and Jewish historical theater piece:

Three of the best-known un-Jewish Jewish artists, gathered in the former residence of the Archbishop of Salzburg [i.e. the Leopoldskron, Reinhardt’s palatial residence], in actual physical view of Berchtesgarden, Hitler’s mountain chalet… pledged themselves to give high dramatic expression to the significance of the people they had forgotten about till Hitler came to power… “I cried. Weill cried. Werfel cried. Finally, Reinhardt cried. Then I knew we had something.” [5]

The work is part Bible pageant and part paean to the fortitude of the Jewish people, whose experience had been summarized, in the most widely read Jewish history work of the day, Heinrich Graetz’s magisterial Die Geschichte der Juden, as one of “Leiden” und “Lernen” (suffering and scholarship).

The story is set in a synagogue in a nameless place—it could be anywhere. Outside, a pogrom is raging, and the Jews, gathered in their house of worship, await their fate. To bolster their morale, their rabbi reads inspirational stories from the Hebrew Bible. Ultimately, they leave to go on their endless road of Exile, but they leave with their dignity intact.[6]

After their initial meeting in May 1934, the creative team gathered in various European locations throughout the summer to develop the project. Weill took to calling it his “Bibelsache,” (“Bible-thing”), but despite the ironic term, he threw himself into the work. For several months, he abandoned other musical projects and worked exclusively on the composition of this piece. This period was the formative time for the change in his sense of connection to his Jewish identity. If Weisgal’s assessment of him in May 1934, as an “un-Jewish Jewish artist” was accurate, if sarcastic, the time and effort invested in this project gave Weill a renewed sense of Jewish identity.

While staying in Reinhard’s Leopoldskron palace in Salzburg, at work on the music for Der Weg der Verheißung, Weill did considerable research into Jewish music. On August 8, 1934, he wrote his father to ask him to mail samples of traditional Jewish music. He specified that he was not looking for newly composed pieces, but rather older ones that typified the Jewish heritage. He asked both for vocal song settings and for wordless “niggunim” that could help him, not as the source of melodies he would transcribe, but rather to serve as an inspiration for his own melody-making.[7]

In his mind, the amount of music called for was as much as for an opera. He quarreled with Werfel on this point, the playwright seeing the music as incidental, but Weill insisting that it was an integral part of the storytelling. He found the work to be exciting and fulfilling. He wrote Reinhardt in October 1934, that he was experiencing greater enthusiasm, working on this project, than he had felt for a long time.[8]

The result was a wide-ranging and powerful score, moving across a variety of Jewish musical genres, including cantorial forms and Jewish folk music:

Weill wrote emotionally vibrant music designed to send hearts and pulses racing. A score for a monumental pageant, it is exactly what it needed to be: generous, accessible, and varied as it moves among what even for Weill is a remarkable array of musical structures… For each character and each section, Weill developed a distinct musical personality. … [9]

Ultimately, Europe was not the venue for the premiere of the work. When Reinhardt visited America in 1935 to stage and then film A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he also lobbied for an American opening, engaging the set designer Norman Bel Geddes to create a spectacular production. Weill left with Lotte Lenya for America in September 1935, to help midwife the production, and thus began the last major chapter of his life.

Many delays beset the intended American production of the work, whose title in English translation was changed to The Eternal Road. Weill remained closely involved in the process of bringing the work to the stage, revising his work, fighting—with partial success only– to keep the music intact and working with the American conductors of the work, Isaac van Grove and Leo Kopp. Ultimately, The Eternal Road opened in January 1937, and had a respectable, although financially disappointing run of 153 performances. Weill never received remuneration; but then again, it had become more and more clear that this was an investment of his spirit. He returned to the music he had composed again and again, recycling it for later pageants on Jewish themes. This project became the soundtrack of the Jewish dimension of the rest of his life.

Two Folksongs of a New Palestine

The Reubenites and the Gadites owned cattle in great numbers. Noting that the lands of Jazer and Gilead were a region suitable for cattle, the Gadites and the Reubenites came to Moses… and said… the land that the LORD has conquered for the community of Israel is cattle country, and your servants have cattle. It would be a favor to us… if this land were given to your servants as a holding; do not move us across the Jordan… We will hasten as shock troops in the van of the Israelites until we have established them in their home… But …we have received our share on the east side of the Jordan.” (Numbers 32:1-2, 5, 17-19)

The biblical story of the tribes that remained outside of the land of Israel but supported their brethren who were settling in the Promised Land is an apt narrative for framing much of Weill’s religious energies in the last decade and a half of his life. Weill immediately felt home in America and embraced an American identity. Despite never losing his “inch-thick” German accent, he resisted speaking German, even with the other Germans refugees in his artistic circle.

Even so, there was room within that American identity for a Jewish identity as well. Like the tribesmen of Reuben and Gad, Weill had found his own Promised Land outside the borders of the Land of Israel. But he remained concerned for the Jewish national enterprise. The Jews marching out of the synagogue at the end of The Eternal Road could finally reach a destination in their ancestral land. If that solution was not the one for him, it was still a viable one for his people.

After the years-long effort required to bring The Eternal Road to the stage, Weill turned to the financially- and professionally- necessary task of establishing himself as a composer in America. There is a hiatus of nearly a half dozen years between the completion of the run of The Eternal Road in 1937 and Weill’s involvement in We Will Never Die, the next major project to have a bearing on the trajectory of his religious life. He spent this time partly in Hollywood and partly in New York, writing a film score, music for radio performances and incidental pieces for the 1939 New York World’s Fair. His greatest accomplishment was in the musical theater. After a few moderately successful efforts, Weill achieved a major triumph with his score for Lady in the Dark, which ran for 467 performances in 1940 and 1941.

Even so, he did produce one smaller effort with religious implications. In 1938, Weill arranged two Zionist folksongs for voice and piano, under the title “Two Folksongs of a New Palestine: Havu l’venim, Ba’a M’nucha.” The two texts are songs of the Zionist pioneers. The first one celebrates a building project, and its title means “Bring Bricks!” The second is a pastoral song of the Valley of the Jezreel, an important region of kibbutz (collective farm) enterprise and one of the main centers of Zionist pioneer settlement. After a day of satisfying work, the farmers enjoy their well-earned rest, but need to remain on guard to protect their “land of glory.” Both songs reflect the Zionist spirit of the pioneers’ maxim: “anu banu ‘artzah livnot ul’hibbanot bah”—we have come to the Land, to build it up and to, ourselves, be built up in it!

Weill’s turn to Zionist songs was not at all a confession of ambivalence about the American identity he was embracing. At the same time as he composed the settings of the two Zionist folk songs, he wrote the music for Knickerbocker Holiday, a retelling of Washington Irving’s stories of colonial New York. He also worked on two other productions retelling the American national story: A Common Glory and The Ballad of Davy Crockett. He immersed himself in Americana, even decorating his home in Early American style. His growing Zionism, therefore, coexisted with a Diasporic identity. The connection of the Jew to the Jewish homeland, for Weill, was a matter of history, not of fulfilling theological mandates.

Here, the contrast to Schoenberg is illuminating. Weill went though no thought process comparable to Schoenberg’s. For Weill, reengagement with Judaism was not accompanied by intense theological speculation. There is no parallel in Weill’s religious trajectory to the poetry, drama and music created by Schoenberg to express the complex of ideas of (1) Judaism as the expression of pure, austere monotheism, and (2) the status of the Jews as God’s Chosen People. For Weill, a growing identification with Zionism was a matter of simple survival. The Jews were existentially threatened; the Free World offered only a partial solution, and so Israel was the answer.

Nonetheless, Weill’s growing warmth to Zionism was clearly also a reflection of his reevaluation of the meaning of his Jewish identity. He had been forced to flee for his life because he was a Jew. The fact that he did not practice the traditions of the religion was irrelevant. The experience of confronting Nazism brought Weill back, if not to religious and ceremonial piety, then certainly to a fuller identification with their people.

Weill experienced this transformation not only as a member of a wave of refugees, but on the more intimate terms of his personal family situation. Weill’s parents and one of his brothers had fled Germany and settled in Palestine by 1935. The elder Weill had been working as the director of a Jewish orphanage in Leipzig, but he could find no work in the land of Israel. Under the circumstances, Kurt helped to support his parents. The Zionist option was now not a matter of other people’s choices. Albeit at a geographical and emotional distance, he was personally involved. The significance of Weill’s Zionist folksong settings in the reconstruction of the trajectory of his religious life is that they are a marker of this changing thinking. Albeit at a geographical and emotional distance, he was personally involved.

We Will Not Die

Conditions, grim enough for German Jews in the half-decade 1933-1938, soon became radically worse. The coordinated attacks upon Jews and Jewish communal institutions of Kristallnacht, November 9-10, 1938, were beginning of the end for German Jewry. If America is a land of freedom, then embracing one’s Americanism can mean joining the political debates of the day without any hesitation. Weill never considered that he lacked the standing to take part in the internal American debate between proponents of isolationism and interventionism. Isolationists were a powerful group in America until the Japanese attack on United States naval forces in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. They expressed the disillusionment of Americans, contemplating the seeming waste of national life and treasure in the Great War and the affairs of Europe since 1914. In the face of this sentiment, interventionists argued that no peace can endure unless Hitler is first defeated. Herbert Agar, a Louisville, Kentucky newspaper editor and a leader within the interventionist camp, summed up the argument: “Tomorrow can be a time for peace if all good men stand together today and fight for freedom.”[10]

In practice, interventionism entailed entering an alliance with Great Britain, then struggling to survive in the war with Nazi Germany. President Roosevelt painstakingly built-up interventionist sentiment. He achieved a legislative victory when Congress passed the Lend Lease Act on March 11, 1941, authorizing the United States to provide military aid for countries at war with Nazi Germany. The measure strengthened Great Britain at a time of critical need.

In 1939, proponents of interventionism against Hitler established the “Fight for Freedom Committee.” Many in the Hollywood film-making community joined this effort, creating a “Stage, Screen, Radio and Arts Division” of the Fight for Freedom Committee. In 1941, a member of that committee, the screenwriter and newspaper columnist, Ben Hecht, wrote a script for a pageant, Fun to be Free, to broadcast the call for America to join the fight. Hecht invited several composers, including Weill and the popular Jewish-American songwriter, Irving Berlin, to provide music for the pageant.

Weill had known Hecht since 1936, when they had discussed possible projects on which to collaborate. When Hecht turned to Weill in August 1941, he found him willing to contribute his talents to the effort. Weill complied enthusiastically and completed the work quickly. He composed some of the music afresh, but also reused music he had previously composed for The Eternal Road and for his unfinished project about the American patriot and pioneer, Davy Crockett.

The pageant opened on October 5, 1941 in New York’s Madison Square Garden. It garnered wide support and energized the public. One must acknowledge, nonetheless, that ultimately none of the efforts of the interventionists to rally Americans for war against Hitler were decisive. The debate ended because Hitler ended it for Americans by declaring war on the United States after Pearl Harbor. After that, the assorted neo-Nazis and remaining isolationists were consigned to the margins of the American political spectrum. Their anti-Semitism continued, but the war effort eclipsed it.

After Pearl Harbor, Weill threw himself into American patriotic work. He shelved work on a symphony to devote himself to war-related causes. He volunteered as a civilian plane spotter, on the lookout for enemy aircraft in the skies over Rockland County, NY. More in keeping with his talents, he composed the incidental music for Your Navy, a morale-building radio program scripted by his collaborator and friend, the playwright Maxwell Anderson. Weill organized 15 of the American Theater Wing’s lunch-hour entertainments for factory workers producing war-related products. Much of that involved presenting existing works of popular music; but Weill himself composed several songs for the war effort, including the anti-Hitler satire, Schicklgruber, which received its premier in June 1942. He also renewed his connection with Brecht, writing the music for Brecht’s anti-Nazi song, “Und was bekam des Soldaten Weib?” (“Ballad of the Soldier’s Wife”) The song spoke of a Wehrmacht officer dying in Russia. It was broadcast to Germans behind the front lines as part of the wartime propaganda campaign. The song received its New York premier in April 1943, with Weill at the piano, accompanying Lotte Lenya.

Weill’s wartime service included one major effort devoted to the overriding Jewish concern of stopping the ongoing Nazi genocide. This was the music he wrote for the pageant, We Will Never Die.

Like Fun to be Free, We Will Never Die was the work of Ben Hecht. One of Hecht’s newspaper columns had caught the attention of a Zionist emissary in America, Peter Bergson. Bergson (the adopted name of Hillel Kook) steered Hecht in the direction of several Zionist causes, including the idea of creating a Jewish fighting force of soldiers from the Jewish settlement in Palestine to join the anti-Nazi coalition. Since Palestine was under British control, ultimately, the “Jewish Brigade” emerged as a unit within the British army. It saw action in Italy for the last phase of the war. But the British were slow to authorize the creation of this force, and in Zionist circles, America’s joining the war effort represented a possible way to gain leverage in the campaign to secure British approval. In America, those advocating for this cause organized the Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews. This Committee was the official sponsor of the pageant.

The pageant was not only a lobbying effort for the creation of a Jewish fighting force. It was also an attempt to raise awareness that the Nazis were massacring Jews on an unparalleled scale. This realization was dawning even in 1942. In late 1942, Ben Hecht invited several dozen prominent Jewish artists and intellectuals to work with him on stimulating public awareness of the genocide taking place. Only two of those to whom he reached out volunteered to help: the theater director and playwright, Moss Hart and Kurt Weill. Hart ultimately directed the show, and Weill contributed all the music.

Why did most of those approached not respond? They may have felt that Hecht, professional gadfly that he was, did not represent a good partner for the effort. Alternately, their unresponsiveness may have been part of the larger issue of the lackluster American Jewish reaction to the disclosure of news of the Nazi genocide. American Jews of that era were mostly willing to trust their military and civilian leaders, who told them that the way to save Jews was to defeat the Nazis. Overall, American Jews, a community largely composed of recent immigrants in the early 1940’s, lacked the self- confidence to agitate for changes in the governmentally set priorities. The individuals and groups who did attempt to influence U.S. policy were a small minority within the American Jewish community. In any case, President Roosevelt gave them no concessions.[11]

Given the near consensus of refusal, Hart’s and Weill’s volunteerism takes on added significance. Hecht recounted the moment in his 1954 autobiography, A Child of the Century: “Kurt Weill, the lone composer present, looked at me with misty eyes. A radiance was in his strong face. ‘Please count on me for everything,’ Kurt said.[12]

Hecht was a master of creatively heightened prose, but there is no reason to doubt that Weill was sincerely committed. He finished his commission with dispatch. We Will Never Die was performed at Madison Square Garden in New York City on March 9, 1943. It then went on tour to five cities, ending its run in Los Angeles.[13] It was part spectacle, part “Memorial Service to the Two Million Jewish Dead of Europe.”

The effect of the campaign to pressure President Roosevelt accomplished little. The U.S. Congress urged the creation of a governmental agency to help Jewish refugees, and President Roosevelt established a War Refugee Board in 1944. But it resettled only a thousand-plus of the vast numbers who needed refuge. More impactful was the Board’s funding of rescue efforts conducted by the Swedish diplomat, Raoul Wallenberg.

At the time of the production of the pageant, Weill was less optimistic than some of the other backers as to the ultimate effect of the work. He dismissed the claims of the Zionist leader, Bergson, that the pageant was “a turning point in Jewish history,” with the remark that Bergson was “stage-struck.” Sadly, Weill was correct.

A Flag is Born

Bergson was also a cause, albeit an indirect one, leading to the next episode in which the religious dimension of Weill’s life came to the fore. Beyond the specific Zionist projects that Bergson sought to foster, his overarching goal was to rally support for the creation of the independent Jewish state of Israel. Bergson reached out to Hecht in order to cultivate an ally and gain a megaphone. In 1942, he brought Hecht into the group that sponsored the March 1943, rally. After the war, Bergson’s group reconstituted itself under a name: now it was the American League for a Free Palestine. Hecht joined this committee, and Bergson continuing to influence him in the direction of Bergson’s political sub-set of the Zionist movement, the “Revisionist Zionist” group.

Revisionist Zionists were the disciples of an early Zionist leader, Vladimir (Ze’ev) Jabotinsky. The major point of dispute between the Zionist establishment and the Revisionist opposition during the Second World War was how to manage relations with the British. Relations between the British administrators of Palestine and the Jewish community there had grown steadily worse since the late 1920’s. In the face of Arab opposition to Zionist immigration, including an armed insurrection in 1936, the British retreated from the mandate assigned to them by the League of Nations, to foster the creation of an independent Jewish state. First, they proposed partitioning the western part of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state (the eastern half already having been separated from Palestine in 1921 and turned into the Kingdom of Transjordan). Then, in 1939, with war looming after the collapse of the Munich accord between Hitler and British Prime Minister Chamberlain, the British abandoned their own partition plan. In their “White Paper” of 1939, they imposed a strict cap on Jewish immigration into the territory and handed the Arabs in Palestine a veto over the future development of the Jewish nation in that land. All Zionists, the main group under Chaim Weizmann (later the first president of Israel) and the revisionist group under Jabotinsky, were determined to oppose the British on this score.

At that point, the war broke out. The Zionist leadership council was faced with an enemy in the British, but a far worse enemy in the Nazis. Over the course of several contentious meetings in the early part of the war, it resolved to assist the British in their fight against the Nazis and to defer the call for independence until after the conclusion of the war.[14] The Jabotinsky faction was vigorously opposed to “giving a pass” to the British, and in the last years of the war, two different militant, anti-British cadres grew out of it.

When the war ended and the scope of the Holocaust became fully clear, the toll was not only six million murdered. There were also a half million European Jewish survivors of the Final Solution. These refugees neither wished to stay, nor were welcome, in the House of the Dead that was Europe. Indeed, a wave of pogroms claimed hundreds of lives of Jews seeking to return to their homes in various Polish cities. Opening the gates to Jewish immigration to Palestine was therefore a national imperative for the Jewish people. The British, still in military control of the territory, and still abiding by their policy of 1939, blockaded the coast and intercepted ships carrying Jewish refugees. They interned them in prison camps, first in Palestine, then in Cyprus, and in the case of the S.S. Exodus 1947, the British returned the refugees to internment camps in Germany.

World Jewry was nearly unanimous in opposing the British exclusion of Jewish immigration to Palestine. But how to express that opposition divided the main body of Zionists and the Revisionists. Mostly, the Zionists practiced non-lethal disobedience, smuggling refugees past the British blockade. The Revisionists, however, advocated armed resistance to the British with the aim of forcing their withdrawal from Palestine, after which the Jewish people would defend itself as necessary.

Tutored in Zionism by Bergson, Hecht was an apostle of Revisionist Zionism. In his columns and open letters, he adopted an incendiary tone, applauding the resistance to the British. In A Flag is Born he expressed that vision in a package wrapped for an American audience. Hecht cast the British in Palestine as latter-day iterations of the hated King George III, who had tyrannized the 13 American colonies. The organizing slogan of his pageant was, “It’s 1776 in Palestine.”

The plot involves three Holocaust survivors, an elderly couple and a young man. When the older man dies, the younger one takes his prayer shawl and fashions it into a battle flag, under which he marches off to Palestine to do battle on behalf of the birth of an Independent State of Israel—hence, the birth of the flag alluded to in the title.[15]

The script of the play completed, Hecht turned to Weill in August 1946, to ask him to supply the music. Deadlines in mind, he gave him a month to complete the assignment.

Weill’s music was never published and is now lost, but a description of it has survived. He included some of his own music originally written for The Eternal Road along with popular melodies: the theme from the Yom Kippur prayer “Kol Nidrei,” Jewish folk songs and American patriotic songs. At the conclusion, he created a quodlibet combining the Zionist anthem, “Hatikvah” with two American standards, “Yankee Doodle” and the First World War anthem, “Over There.”[16]

A Flag is Born opened on schedule, Sept 5, 1946. It was quite popular, both in New York and in five other cities, ultimately netting over $400,000 for the activities of the American League for a Free Palestine. It may seem odd that Weill, a man of progressive political tendencies, should have joined forces with Hecht, himself a disciple of the right wing of the Zionist movement. But having written music for such a play does not lead to the conclusion that Weill was himself an apostle of Zionist Revisionism. He wrote to Maxwell and his wife Mab Anderson disparagingly of Hecht’s “silly one-man campaign against the English empire.”[17]

Zionism appealed to people espousing a variety of worldviews. Nationalists like Jabotinsky, Schoenberg and Ben Hecht focused on the political needs of the Jewish people. But liberals such as Weill were also enamored of the Zionist cause. It spoke to Weill’s universalist concerns for victims of oppression as well as to his more personal desire to see the Jewish people get some consideration after having suffered so grievously at the hands of the Third Reich. Weill made this point explicitly in a 1949 radio interview.[18]

Moreover, in considering the alacrity with which Weill responded to Hecht’s overtures, it is good to recall that Weill’s approach to music-making was that of the man of the theater. It was collaborative. Others wrote the text; he set the words to music. Sometimes the music went in a different direction than the words, but by and large, it partnered with the text to achieve a dramatic message. Beyond any specific disagreements that Weill had with Hecht’s political preferences, Weill approved of the message here, broadly speaking: the Jewish people need their state.

It was not simply a matter of being unable to say “no” to the charismatic Ben Hecht. Weill’s Zionism was genuine. He had not been a Zionist in his youth (as is seen in his letter to his mother of December 31, 1924), but the encounter with Nazism changed his views permanently. While he was personally happy to be an American, he thought it necessary for the Jewish people to have the respect of the world that was represented by an independent, Jewish state, “so that we will not be trampled upon again.” When the State of Israel declared its independence, in May 1948, he declared to his parents how proud he was to see the courage and strength of Israel on display before the entire world. He wrote that it must be a beautiful feeling that his parents were cherishing, that as citizens of the new state, they had taken part in the realization of a great idea of world-historical significance. When the Israeli War of Independence had concluded, Weill wrote his parents how pleased he was that his arrangement of the “Hatikvah” was performed at the dinner honoring the Israeli president, Chaim Weizmann, then visiting New York. Weill also wrote his parents to tell them that Lenya shared in his Zionism. She participated in a benefit concert for Israeli children on May 16, 1949.[19]

Weill’s Synagogue Composition: Kiddush

Reviewing the compositions Weill wrote between 1935 and 1946 that dealt with Jewish themes, it is striking that they all dealt with the national experience of the Jewish people and not the specifically religious heritage of Judaism. Was the adult Weill, having left synagogue Judaism behind, fully to be understood thereafter as participating in Jewish causes because he had been a refugee from Nazism, and was, as such, sympathetic to Jewish suffering and eager to see justice done for the Jew? Or, at some level, were specifically religious concerns still meaningful for Weill, even if he did not weave them into the fabric of his life?

Like Schoenberg, Weill composed one work intended for use in the synagogue. Unlike Schoenberg, Weill’s work has been incorporated into synagogue practice, and it is a welcome, if infrequent, addition to Jewish liturgical music. This work is the Kiddush, a prayer recited at the Friday night Sabbath eve worship service. The prayer was originally intended for home recitation at the Sabbath dinner table. It involves taking a cup of wine (or grape juice) in hand, blessing God as the Creator of the fruit of the vine and praising God for having established the Day of Rest. The prayer began to be recited in the synagogue in the Middle Ages, when synagogues served as hostels for travelers stranded over the Sabbath without home hospitality. Since the Kiddush was (and is) traditionally recited at home by the head of the household, it became standard for the cantor or other prayer leader to stand in as surrogate head of household and to recite the Kiddush at Sabbath eve services. In the 19th century, this prayer became a vehicle for the cantor to sing as virtuoso soloist, accompanied by a male choir in Orthodox congregations, and by a mixed choir and organ in Reform congregations.

Even though the Kiddush is Weill’s sole composition for the synagogue, the occasion for its composition was part of the pattern of his life: As was so often the case with this creative production, Weill was responding to an invitation to be part of a collaborative effort. In this instance, Cantor David Putterman initiated the process. The various biographies of Weill explain the context of the invitation only sketchily. We learn, for example, that the occasion was the 75th anniversary of the Park Avenue synagogue. But was the practice of musical commissions at all standard for congregations? Why did the invitation to write such a piece would come from where it did? Why was Weill, not known for any previous synagogue compositions, contacted? That lacuna may now be addressed:

David Putterman was one of America’s leading cantors. He had been serving in the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York City, one of the flagship congregations of the centrist “Conservative” Jewish denomination, since 1933. A part of the back-story of the commission, therefore, is the pride of a leading congregation in being a participant in the creation of new Jewish culture. In 1943, Cantor Putterman had begun the practice of inviting both aspiring and established composers, Jewish and non-Jewish alike, to contribute sophisticated compositions for the synagogue liturgy. He approached Weill for the fourth annual Sabbath service featuring new music.

Weill was not the only composer featured in the program, which was the synagogue’s Sabbath eve service for May 10, 1946:

The other offerings that evening— all composed especially for that service—included settings of [several of the standard Sabbath eve prayers:] “ma tovu” (Numbers 24:5, in English translation) by Alexandre Tansman; “l’ma’an tizk’ru” (Numbers 15:40) by Nicolai Berezowsky; “kaddish” by Ernst Levy; “tov l’hodot” (Psalm 92:1) by Arthur Berger; “May the Words of My Mouth” (Psalm 19:15)… by Paul Pisk; and two by non-Jewish composers: Roy Harris’ “mi khamokha” (Exodus 15: 11) and Psalm 24 by William Grant Still, probably the first Black American composer to write for a synagogue service.[20]

The denominational setting of Conservative Judaism is also important for the understanding of the outreach to Weill and his fellow composers. Despite the misnomer of the adjective “Conservative” in its name, Conservative Judaism is in fact a centrist denomination. When it crystallized in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it came to be called “Conservative” because it called for the conservation of older Jewish norms of behavior, such as the Mosaic and Rabbinic dietary laws, as against the Reform movement’s willingness to dispense with them. On the other hand, unlike the uncompromising traditionalism of Jewish Orthodoxy, Conservative Judaism believed in the gradual evolution of the faith’s ritual and ceremonial norms.

Conservative Jewish leaders of mid-century typically spoke of their movement as distinguished from other denominations by its balance of tradition and change.[21] The implication of that stance for the synagogue explains the context of Cantor Putterman’s outreach to the composers of his day. Culturally, a balancing of tradition and change meant, on the one hand, preserving Hebrew as the preponderant language of prayer, rather than praying mostly in English, and on the other hand, commissioning new musical settings for the standard prayers.

At the same time as Cantor Putterman approached Weill, the programmatic vision of Conservative Judaism was articulated by Rabbi Robert Gordis, chair of the (Conservative movement’s) “Joint Prayer Book Committee”. Quoting the early-twentieth-century Israeli Chief Rabbi, Abraham Isaak Kook, but with a new valence, appropriate to the American Jewish community, Gordis summarized the liturgical work of Conservative Judaism of that time:

“Ha-yashan yitchadesh, v’-he-chadash yitkadesh”

“The old must become renewed and the new become sacred.”[22]

In line with this maxim, Cantor Putterman looked to renew the old statutory prayers of the Jewish prayer book, including, of course, the Kiddush prayer, by presenting them in a new, American-sounding musical idiom, and simultaneously sanctifying the secular idiom by wedding it to a traditional liturgical text.

While Cantor Putterman had begun the program in 1943, the self-understanding on the part of Conservative Judaism that its position was to integrate tradition and change became even stronger after 1945. In the first years after the conclusion of the Second World War, as the full extent of the Holocaust became clear to American Jews, that community came to the realization that it was now at the center of gravity of world Jewry. That realization registered across the spectrum of American Jewish life; but it had special resonance in the Conservative movement. Its leaders responded with a sense of mission, to place American Jewry at the fulcrum of American life.

The movement was structured as a series of congregations served by one central school, the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. The Chancellor of that seminary was the de facto head of the denomination. In the 1940’s, the Chancellor was Rabbi Louis Finkelstein. A dynamic figure, whose portrait once graced a Time magazine cover, Finkelstein espoused a vision of the important role that American Jewry could play in marshalling American religious leaders, Jewish and Gentile, to address the pressing problems of the day. Finkelstein was a pioneer in inter-religious dialogue. He created at the Jewish Theological Seminary an Institute of Religious and Social Studies at which religious leaders of many faiths could gather, share insights, and collectively influence American life for the better.[23] Outreach beyond the established voices in the Jewish community was the order of the day.

As one of the leading cantors of this denomination, Cantor Putterman shared this vision and sought to implement it musically. Over the course of his multi-year program of outreach, he engaged a host of composers, both established and rising, to contribute their work for the synagogue. While the 1946 roster is quite impressive, the full list of composers goes even further, including, in addition to those represented in the 1946 program, David Amram, Leonard Bernstein, Ernest Bloch, David Diamond, Lukas Foss, Morton Gould and Darius Milhaud. Since cultural Zionism was also an active part of the program of Conservative Judaism, Cantor Putterman also reached out to Israeli composers, including the dean of the Israeli musical scene, Paul Ben-Haim.[24]

Given this framework, the fact that Weill had no previous synagogue compositions in his catalog was a plus, not a minus. Some of the other composers whom Cantor Putterman approached were likewise new to synagogue composition. The cantor wanted to extend the connection between Judaism and general culture. Composers who were in sympathy with that aim were welcome to expand in the direction of synagogue composition. He reassured each of the composers that he would exert no pressure on them to curtail their preferred stylistic language. This was in service of his goal, “to accumulate an expanded repertoire of sophisticated works for American synagogue services whose worshippers were no strangers to the variety of contemporaneous developments in the concert world.”[25] For its part, his synagogue, as a leading congregation within the denomination, would enjoy the cachet of having been a patron of the cultural enrichment of Judaism.

The Weill Kiddush entered the repertoire and continues to be performed in synagogue settings. The piece is also heard at Jewish choral festivals.[26] While the concerns of this essay are historical, and detailed musicological analysis is generally not within its purview, it is relevant at this point to explicate the musical idiom of Weill’s Kiddush, so as to enhance the understanding of how it fits within Weill’s catalogue of works and also of what, if any, meta-musical, religious message the work may carry. The idiom is that of jazz, the distinctively American musical genre that has enriched American music, classical as well as popular, since Gershwin’s 1924 sensation, Rhapsody in Blue. To understand how jazz generates its distinctive sound, a short primer in music theory is appropriate:

Musical pitches are (conventionally) organized in scales, a series of ascending pitch tones. (We recall that Schoenberg’s revolution was to upend that fundamental ordering.) The first degree of the scale is the tonic, or home, degree. In jazz, the third degree of the musical scale is neither simply a whole pitch tone above the second degree, as in the musical “major” scale nor a half pitch tone above it, as in the musical “minor” scale. The third degree of the scale alternates between the “major” and the “minor” intervals. This is a so-called “blue” note. The same treatment is given to the fifth and seventh degrees of the scale. They are presented both in the “major” and the “minor” (flatted) pitches. The dissonance arising from this juxtaposition is one of the key ingredients in the distinctive sound of jazz.[27]

The alternation of major-third and minor-third is a prominent feature of the basic melody of Weill’s Kiddush. In the first measure of the piece, the organ accompaniment establishes a major scale by means of sounding the major third pitch. After one measure, the choir joins in, likewise in the major scale, but then immediately sounds the “blue note” of the minor third. Similarly, when the melody reaches the seventh degree of the scale, at the end of the first line of the prayer text, that note is flattened, blues-style. This “bluesy” sonority characterizes the entire piece.

Is there a meta-musical message in this compositional choice? A recent Weill biographer, Stephen Hinton, suggests that it may be a political statement: “Why the blues idiom? Perhaps because by invoking a musical ‘intonation’ itself traditionally identified with ‘the suffering of underprivileged people,’ Weill could make an ecumenical gesture, beyond any single ethnic identity.”[28]

Hinton’s reference is to the African and African American roots of jazz. Hence, incorporating a jazz gesture into a synagogue piece is a signal to keep in mind, at least at some level, the experience of Africans and African Americans, and thus to universalize the Jewish prayer beyond its (putative) ethnic horizons. There is no doubt that Weill drew the connection between the Jewish experience of oppression and that of other groups and that he wanted to raise the consciousness of his audience to work for social justice. That very concern motivated him to renew his partnership with the lyricist Maxwell Anderson and to compose the music for Lost in the Stars, a musical theater adaptation of Alan Paton’s novel of oppression of Blacks in South Africa, Cry the Beloved Country.

But it does not follow that this concern for social justice accounts for Weill’s Kiddush compositional choices. Although he wrote fluently in several styles, the jazz idiom was Weill’s home-base. In particular, the major third/minor third juxtaposition is a fixture of the refrains of “September Song” from Knickerbocker Holiday of 1938 and, older still, of “Surabaya-Johnny” from Happy End of 1929—this is almost a stylistic cliché, and examples could be readily multiplied. Its inclusion in any individual piece is not a departure from Weill’s compositional norm calling for commentary.

If we are to search for a meta-musical message, I would propose that we look at the complex of associations that Weill entertained regarding traditional cantorial chant, and hence his father, the cantor of his formative life experience. Weill, the consummate musical craftsman, was always aware of the intended setting of his pieces, be that the concert hall, the theater, the cabaret, or the pageant. In this instance, Weill was writing not for any of those venues, but for the synagogue. From childhood, from his research a decade earlier for The Eternal Road, and perhaps refreshed in his detailed conversations with Cantor Putterman, he certainly knew the relevant musical traditions governing the rendition of the Sabbath-eve Kiddush. In “Ashkenazic” (central and eastern European) Jewish practice, that prayer is traditionally rendered in the major key. [29] It is therefore not surprising that the Cantor’s opening phrases are sung in the major. The choir, on the other hand, supplies the “jazzy” chromatic notes. Then, at the end of the cantor’s first strophe, he sings the “blue note” flatted seventh.[30] The choir then responds with a prominent flourish, highlighting all the distinctively colored notes of the jazz scale, i.e. the flatted fifth and third degrees. From this alteration, it emerges that the cantor represents the voice of traditional Judaism, and the choir, the popular milieu.[31]

Following this analysis, I offer the following hypothesis as to a meta-message in Weill’s composition: The voice of tradition and the voice of the people need to be brought into harmony, and more specifically, into a new kind of harmony dictated by the changing norms of life. The Jewish musical inheritance can survive and even thrive if it is open to the wider musical milieu.

This programmatic point, moreover, is even truer in America than it had been in the Germany of Weill’s Jewish childhood, because the society into which Jews were acculturating was that much more open to Jewish participation, and hence American Judaism itself was more open to cultural imports than ever before. This hypothesis is hopefully persuasive; but it remains speculative. What is more certain is that, in Weill’s mind, the piece was emotionally significant. He did not treat it as an ordinary commission. He refused payment for the piece. He also gave permission for it to be reprinted without compensation. Clearly, he wanted this piece to serve as a gift.

To whom? Narrowly, it was a gift to one Jewish congregation, but Weill had no ties to the Park Avenue synagogue. He was not seeking to make his name as a synagogue composer, so this work was not in any sense an investment. It was more of a gift to the Jewish people, then rebuilding after the immense losses, cultural as well as demographic, in the Holocaust.

It was also a gift in a much more personal sense. Weill dedicated the Kiddush “To my father.” He did not write, “To Cantor Albert Weill”, but “To my father.” We know that the filial piety was Weill’s express intent, because, in accepting the invitation to compose the Kiddush, he told Cantor Putterman that “it would be his chance to clear his conscience with his father.”[32] He needed to “clear his conscience” because he had deeply disappointed his father (and his mother) by marrying out of the faith and abandoning a life of religious piety. Wounded, his parents had not attended his wedding. That was a norm in the Jewish society of the day.

This was not the first musical composition that Weill dedicated to his father. Eleven years earlier, in the first of his projects related to his Jewish identity, The Eternal Road, one of the songs he set was a text describing God’s promise of a special covenant with Father Abraham. Weill dedicated that song to his father. The symbolism is obvious, and the timing of the gesture underscores its serious intent—Weill was working on this music in 1935, as the Nazis were imposing the Nuremberg Laws, stripping the Jews of Germany of their Emancipated status.[33]

Although having rejected their religious lifestyle, Weill never broke off relations with his parents. He continued to write solicitous and often up-beat letters to them, and Lotte Lenya added her postscripts.

He also undertook practical measures to remain on good terms with his parents and to help them when necessary. In 1935, when Albert and Emma Weill fled the worsening conditions for Jews in Germany and immigrated to Palestine, they were already elderly and were unable to find employment. Responding to their need, Kurt helped support them. In the 1940’s, his regular contribution was $125 per month, not an inconsiderable sum of money for those times.[34] In 1941, when the Wehrmacht under General Rommel was advancing eastward across North Africa and getting closer to Palestine, Weill tried (unsuccessfully) to arrange for their safe transplantation to the United States.

But the break had not fully healed. At the time of writing the Kiddush, he obviously still felt that he needed to make a gesture. This composition was precisely that gesture. In it, Weill honored his father in a most meaningful way. As an extended solo, the Kiddush is one of the moments in the traditional Sabbath eve prayer when the cantor shines. Of the various prayers composing the Sabbath eve liturgy, the Kiddush is often the one given the most elaborate and florid cantorial rendition. To dedicate a setting of the Kiddush to one’s father, the cantor of one’s childhood experience of religion, is a deep tribute. It honors the man by taking a text symbolic of his own lifework as the base text for the creation of a new work of art.

Weill was to make another gesture of filial concern and emotional reconnection a year later. In May 1947, Weill traveled to Europe and Palestine, visiting his parents for the first time since his sudden departure from Germany in 1933. He expressed joy and relief at seeing them living in “a real Paradise.” After the visit had concluded, he wrote again, speaking of his intention to return to Israel, but this was in fact the last time he was to see his parents before his premature death in 1950.[35] Despite his gestures of homecoming, Weill did not end up, religiously, in the same place as Schoenberg. He did not make any declarations about focusing on religious music. He did not compose his own psalms. What he did do was inject a vaguely spiritualized and humanistic message into his last work.

The final years of Weill’s life coincided with the opening phase of the Cold War. That conflict had an impact upon religious life in America. Identifying their country as the opposite of the atheist communists of the Soviet Union and China, Americans emphasized religiosity, while downplaying the differences between one religious denomination and another. One of the popular American narratives of the day identified working for social justice as a religious concern that united countrymen of several faiths. This was certainly true of liberal Jews.

This is the religious context of Weill’s final years. His membership, as a Jew, in an oft-persecuted group dovetailed neatly with his espousal of the liberal cause of uplifting other ethnicities who were suffering oppression. His last completed project, composing the music for Maxwell Anderson’s Lost in the Stars, an adaptation of Alan Paton’s novel, Cry, the Beloved Country, gives voice to Weill’s desire to do something positive on behalf of oppressed African Americans by raising public consciousness to the evils of apartheid.

This kind of religiosity is warm to ecumenism rather than particularism. Weill found it congenial. In Weill’s last letter to his parents, written eight weeks before his untimely death, he told them of the award that the National Conference of Christians and Jews, a prominent ecumenical organization, had given to his collaborator Maxwell Anderson for having written the book of Lost in the Stars. That organization applauded the work for its advocacy of inter-racial harmony. Weill told his parents approvingly that Anderson, in accepting the award, pointed out that he was the son of a Protestant pastor, and his collaborator, Weill, the son of a Jewish Cantor. Anderson emphasized that the two of them had already experienced their private unification of Christians and Jews.[36]

Since that was, literally, Weill’s last written word on his religious journey, it is appropriate to have its message remain in the stage light, as the rest of the stage fades to black. He ended his days as a Jewish humanitarian— nonobservant of Jewish rituals, disengaged from the piety of his ancestors, but proud of his identity and willing to acknowledge it as part of his effort to make the world better. That was the conclusion of the arc of development that took Weill from Wilhelmine Germany to the Weimar Republic, and from France to America in the German Diaspora. His tombstone epitaph can be understood in that spirit. Underneath his name and the timespan of his life, 1900-1950 are inscribed four lines from Lost in the Stars:

This is the life of men on earth

Out of darkness we come at birth

Into a lamplit world, and then—

Go forward into dark again.

The lyrics are not overtly religious, but their setting in the musical was as a hymn recited by the African worshipers in their chapel. Religion remained a context, if not an explicitly stated theme.

There remains a final parallel between the Biblical Aaron and Kurt Weill: Take Aaron and his son Eleazar and bring them up on Mount Hor… Aaron died there on summit of the mountain. When Moses and Eleazar came down from the mountain, the whole community knew that Aaron had breathed his last. All the house of Israel bewailed Aaron thirty days. (Numbers 20:25, 28-29)

Musically, Weill’s career had two halves. In each one, he scaled a height. First, he transformed classical music in Weimar Germany by the Singspiel genre that he and Brecht co-created. Second, he mastered the idiom of musical theater in America and enriched it with works of distinction. Like the biblical Aaron, he started in a country—Germany– that became an “Egypt” to him; and like Aaron, he was at a pinnacle when he died.

Conclusion: Arnold Schoenberg, Kurt Weill, and the Variations on the Theme of Jewish Identity

Schoenberg’s and Weill’s religious journeys illustrate two of the possibilities in the spectrum of post-traditional Jewish identities seen in modern times. Their reconstructed identities are “post-traditional” because, in each case, the traditional channels of expressing Jewishness did not endure. Each one abandoned the distinctive ceremonial practices of Judaism, such as the dietary laws, the observance of the Jewish Sabbath and holidays, affiliation with a synagogue and the like. Each one married outside the faith community. And yet, each one reaffirmed a sense of Jewishness.

The first element of their reconstructed identities, therefore, was simply their affirmation. But their Jewishness did not end there. Based on that affirmation, each of them expressed their Jewishness creatively, at least on occasion. Weill’s pageant music and folksong settings, Schoenberg’s play, opera, cantata and several song settings all dealt with themes emerging from the Hebrew Bible and Jewish history.

A non-Jewish composer could certainly write music on such material. For example, Max Bruch, a Christian, composed a setting of the Kol Nidrei. But in such cases, the composer was working within the popular, nineteenth-century tradition of creating characteristic pieces in the style of various nationalities. Bruch was German, and he composed a Scottish Fantasy. Georges Bizet, the French composer, the Russian Peter Tchaikovsky and the Polish Moritz Moszkowski, all wrote “Spanish” music. Examples of this abound. For such composers, dealing with the musical traditions of one nation or another was a channel of expressing themselves musically in an era of nationalism.

By contrast, as we know from the biographical context of Schoenberg’s and Weill’s work on Jewish subjects, their compositions were active expressions of their identities as Jews. In this regard, their synagogue compositions are especially significant. Among the motivations leading Schoenberg to set the Kol Nidrei was his discovery that the prayer was intended for people returning to the Jewish faith after having been outside that circle. He wrote in a similar vein about the Shema Yisrael prayer that he included in “A Survivor from Warsaw.” Jewish prayers expressing a resumption of one’s earlier- forgotten or abandoned Jewish identity spoke to him personally. Weill spoke about his setting of the Kiddush prayer in terms of his relationship with his father, a synagogue cantor.

For both composers, a significant part of their religious identification was their concern for the welfare of the Jewish people. This is a part of traditional Jewish identity that often endures in post-traditional Jewishness. Each of them invested considerable time and energy into attempts to raise consciousness about the Holocaust. To varying degrees, each of them helped at the personal level to rescue Jews, fleeing Nazi oppression. Originally an unpopular option within the Jewish world, Zionism became part of the mainstream Jewish agenda as a result of the scourge of Nazism and the trauma of the Holocaust. The adoption of Zionism by Schoenberg and Weill were instances of this process by which Zionism became a near-consensus concern of the Jewish people.

Beyond these similarities, however, there were significant divergences in the nuances of their Jewish identities. Schoenberg had conservative and even authoritarian leanings, whereas Weill was at home in the liberal constellation of values and priorities. For that reason, when Schoenberg embraced the cause of Jewish nationalism, he elevated particularistic values to prominence within his worldview. He replaced his earlier focus on humanity’s struggles with a consuming concern for that which distinguished Judaism from other faith communities: an austere form of monotheism, the idea of the Chosen People and the specific historical experience of the Jewish people. Weill, by contrast, expressly framed his concern for the Jewish nation and the Jewish state as a subset of his universalist, humanitarian concerns. In both their similarities and differences, Schoenberg and Weill represent, in microcosm, the pathways taken by significant numbers of Jews in western society in modern times.

Footnotes:

[1] My analysis of the Jewish identity of Arnold Schoenberg, a companion essay to this one, appeared in Glossen 45: “Variations on a Theme: The Reconstructed Jewish Identities of Arnold Schoenberg and Kurt Weill. Part One: Arnold Schoenberg: The Mystique of Moses.”

[2] Weill, Kurt. Essay in Berliner Tageblatt, October 1, 1927. Reprinted in: A New Orpheus: Essays on Kurt Weill. Ed. Kim Kowalke. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

[3] Sanders, Ronald. The Days Grow Short: The Life and Music of Kurt Weill. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1980, p. 202.

[4] Hirsch, Foster. Kurt Weill on Stage: From Berlin to Broadway. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002, p. 118; Sanders, p. 203.

[5] Weisgal, Meyer. So Far, New York, 1971, p. 121- Quoted in Schebera, Jürgen. Kurt Weill: An Illustrated Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995, p. 234.

[6] From today’s perspective, this is reminiscent of the end of the Norman Jewison film version of the Broadway play, Fiddler on the Roof, 1971. When Der Weg der Verheißung was staged in Chemnitz, Germany, in 1999, the ending was changed, in view of the Holocaust. A Nazi soldier guns the rabbi to death when the rabbi refuses to burn the Torah scroll that he was cradling. The stage fades to black on the assembled Jews, symbolizing their destruction in the Holocaust. One boy emerges from the mass of victims, remaining bathed in light, symbolizing the saved remnant, the “brand, plucked from the fire”, in the language of the Biblical passage Zechariah 3:2. See the documentary video by Ron Frank, The Eternal Road: Kurt Weill, Max Reinhardt and Meyer Weisgal’s Operatic Jewish Response to Hitler’s Germany (Kultur, 2000).

[7] Kurt Weill Briefe an die Familie (1914-1950). Ed. Lys Symonette and Elmar Juchem. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 2000, letter #211, p. 342.

[8] Quoted in Taylor, p. 206.

[9] Hirsch: p. 153. See the detailed description of the music in: Drew, David. Kurt Weill: A Handbook. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 1987, pp. 262-268, 280-282. Excerpts of the music can be heard in Frank’s documentary film about the 1999 staging of the piece.

[10] “From literary gadfly to Jewish activist: the political transformation of Ben Hecht.” The Free Library, 2003. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/From+literary+gadfly+to+Jewish+activist%3a+the+political+transformation…-a0136342704.

[11] Wyman, David. The Abandonment of the Jews: America and the Holocaust, 1941-1945. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984, pp. 311-330.

[12] Quoted in Taylor, p. 278.

[13] Hirsch, p. 214.

[14] Sachar, Howard M. A History of Israel. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991, p. 230.

[15] Medoff, op. cit.

[16] Hirsch, p. 260.

[17] Taylor, p. 296.

[18] Hinton, Stephen. Kurt Weill’s Musical Theater: Stages of Reform. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012, p. 259.

[19] Briefe #175, Dec. 31, 1924, #245, Jan. 22, 1948, and #246, June 24, 1948.

[20] Milken Archive. “Swing His Praises—liner notes for Weill ‘Kiddush’.” Roy Harris set to music was the same text that Schoenberg had declined to set, three years earlier.

[21] Waxman, Mordecai (ed.). Tradition and Change: The Development of the Conservative Movement. New York: Burning Bush Press, 1958, pp. 19-20.

[22] Gordis, Robert. “Introduction to Rabbinical Assembly.” In: Sabbath and Festival Prayerbook, 1946, xiii.

[23] Greenbaum, Michael. Louis Finkelstein and the Conservative Movement: Conflict and Growth. New York: Global Publications, 2001, pp. 47-102.

[24] New York Times obituary, David Putterman, October 12, 1979. Putterman’s promotion of cultural Zionism in the American Jewish synagogue registered on other congregations within the denomination. At the time, my father, Rabbi David H. Panitz, was serving as associate rabbi of B’nai Jeshurun, a near neighbor of the Park Avenue Synagogue in New York City. He engaged an Israeli chamber ensemble, the “Palestine String Quartet,” to perform at his congregation. The lay leadership of the congregation was miffed at the alleged extravagance of his payment. (He had contracted to pay them $125.) In an unconscious display of Philistinism, the congregation’s president challenged Rabbi Panitz: “For that kind of money, couldn’t you at least have gotten a 5-piece quartet!?” Three decades later, serving as rabbi of Temple Emanuel in Paterson, N.J., Panitz commissioned the German-born, Israeli raised composer Gershon Kingsley to compose a cantata setting to music the words of the Rabbinic ethical treatise, “Pirke Avot.”

[25] Milken Archive, liner notes, “Weill, Kiddush.”

[26] When I attended Sabbath evening worship services at the aforementioned Temple Emanuel of Paterson, NJ, during the 1960’s-1980’s, Weill’s Kiddush was often programmed. The reason for its inclusion at that one congregation more frequently than the national average is no doubt the influence of one man, the synagogue composer Max Helfman. Helfman was the conductor of the Hebrew Arts Singers, who supplemented Cantor Putterman’s synagogue choir in 1946. Helfman also worked part-time as conductor of the choir of the New Jersey Temple Emanuel and added the piece to its repertoire.

[27] Bernstein, Leonard. “The World of Jazz.” Telecast of October 16, 1955, printed in The Joy of Music. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1959, pp. 94-100.

[28] Hinton, Stephen. Kurt Weill’s Musical Theater: Stages of Reform. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012, p. 259.

[29] See “Kiddush #3, a notation of the traditional melody, and the Kiddush prayer excerpt, “Ki Vonu Vocharto,” by Louis Lewandowski, in Gershon Ephros, Cantorial Anthology. New York: Bloch Publishing Co., 1953. Lewandowski was the leading central-European cantorial composer in the late 19th century. These two renditions were no doubt staples of Weill’s childhood, growing up in the German home and synagogue of his father, Cantor Albert Weill. Note that both compositions are in the major key.

[30] The masculine pronoun is intentional. Weill wrote the cantorial solo specifically for Cantor Putterman. In 1946, women were not yet serving as cantorial soloists and as invested cantors. That change was a result of the feminist revolution in American Jewish life of the 1970’s-1980’s. Women cantors and soloists now sing the cantorial role of the Weill Kiddush. The performance of the work by the Zamir Chorale of Boston, with a female soloist, is available at “Kiddush by Kurt Weill—Zamir Chorale of Boston— “America’s foremost Jewish Ensemble” —Bing video.

[31] One of the leading Weill scholars to analyze this work, Ronald Sanders, reaches a similar conclusion, albeit without presenting the analytical apparatus of my foregoing analysis: “The piece… is a remarkable synthesis of elements in its composer’s sensibility. The passages sung by the cantor alone have a traditional Jewish sound, with just the slightest hint of an American blues to them. The passages sung responsively by the chorus are almost pure Broadway…” Sanders, p. 345.

[32] Sanders, p. 346.

[33] Sanders, p. 214.

[34] Taylor, p. 268.

[35] Briefe, letter #243, June 12, 1947, p. 408 and letter 244, November 1947, p. 409.

[36] Briefe, letter. #253, Feb. 5, 1950, p. 426.

Comments Off on III. Kulturgeschichtliche Analysen: Kurt Weill: Connecting Continents and Cultures