Sep 09 2020

II. Kulturgeschichtliche Analysen: The Reconstructed Jewish Identities of Arnold Schoenberg and Kurt Weill. Part One

Variations on a Theme:

The Reconstructed Jewish Identities

of Arnold Schoenberg and Kurt Weill.

Part One: Arnold Schoenberg:

The Mystique of Moses

Michael Panitz, Norfolk, Virginia

Essay abstract: This essay delineates two different ways of expressing Jewish identity in the post-traditional society of the twentieth-century West, by focusing on the religious trajectories in the lives of two Central-European Jewish composers, Arnold Schoenberg and Kurt Weill. The first installment of the essay, presented in Glossen #45, analyzes Schoenberg’s Jewish identity, establishing that it was a mix of austere monotheism, biblical engagement and Jewish nationalism. The second installment, to be published in Glossen #46, will analyze the Jewish identity of Kurt Weill, quite different from that of Schoenberg, despite the involvement in retelling the stories of the Hebrew Bible and the support of Jewish Nationalism that both composers shared.

***

Being Jewish has meant radically different things at different times and in different social contexts. In traditional Jewish society, it included beliefs, actions and affiliations. The traditional Jew affirmed a set of propositions about God, God’s relationship to the world, to humanity and the Jewish people. He or she also conformed to the behavioral norms of Jewish tradition and associated with the Jewish community. But in the post-traditional Jewish society that emerged in the West since the nineteenth century, professing one’s Jewish identity did not necessarily entail adhering to conventional religious forms. In a changed social context, one could express one’s Jewishness by participating in nationalist or humanitarian causes, or by embarking on individual spiritual quests, even in the absence of the earlier markers of identification.

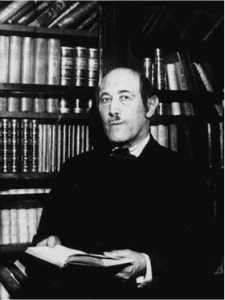

Two twentieth-century composers, Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) and Kurt Weill (1900-1950), abandoned or de-emphasized their Jewish heritage as young adults and then reconstructed their Jewish identities over the course of their lives. An important component of those acts of reconstruction for each composer was an extended investment of creative energies in retelling the stories of the Bible. This essay examines the religious trajectories of their life journeys and elucidates the role of their engagement with the Bible in expressing their Jewishness.

The two composers emerged from much the same musical background, but their paths diverged significantly. Schoenberg remained at the very center of an elitist, modernist circle, the post-tonal composers and consumers of classical music in the first half of the twentieth century. Schoenberg was the first major champion of creating music whose tonal organization was unrelated to the simpler scales of earlier classical music and of the popular music of his era. He regarded his efforts as path-breaking and predicted that he would be vindicated by future audiences. He was harshly critical of composers, specifically including Weill, who failed to move beyond traditional tonality. Weill reciprocated the criticism. For his part, he adamantly rejected the accusation that he had “sold out” after the period of his early, elitist compositions in order to become a popular composer. He was vitally concerned for the connection between composer and public and insisted that the only important distinction was between good and bad music, not between classical and popular music. For Weill, Schoenberg typified the composer who had lost the living contact with his audience.[1]

Their mutual antipathy notwithstanding, the parallels between the two composers are numerous and significant enough to suggest the fruitfulness of examining them synoptically. Each was born into a post-Emancipation Central European Jewish household and was raised within that faith. By their 20’s, each had moved away from their faith community of origin. Schoenberg formally converted to Protestant Christianity; Weill simply abandoned Jewish practice. Each married out of the faith, which was most commonly a decisive act of disaffiliation from the Jewish society of their day. Each one, however, reconnected with his Jewish identity, in large part because of their confrontations with anti-Semitism and Nazism. Schoenberg and Weill each fled Nazi Germany shortly after Hitler took power, ultimately settling in the United States. Each became involved in various forms of political as well as cultural resistance to the Nazis. As part of that resistance, each embraced Jewish nationalism, and more particularly, each had a connection to one of the splinter groups within the Zionist movement, the anti-British camp of Revisionist Zionism. Musically, each one devoted significant creative energy to retelling the stories of the Bible. Despite remaining uninvolved with synagogue Judaism after their re-engagement with their faith of origin, each wrote one significant musical composition for the synagogue worship service. Finally, each one exemplified a concern for values that they consciously associated with the Jewish religion.

In view of the engagement of each composer with the biblical stories of Egyptian slavery, Liberation and Covenant with God, and of Schoenberg’s preoccupation with the biblical figures of Moses and Aaron, in this essay, biblical quotations will serve as a structural device to frame the various milestones along the religious paths of the two composers’ lives. These biblical references establish an analogy between the life of Moses and Arnold Schoenberg, and, to a lesser degree, the life of Aaron and Kurt Weill. As with all analogies, they are admittedly approximate, and cease to be helpful if they are taken too far. But in Schoenberg’s case, especially, there is evidence that he incorporated his interpretation of the biblical Moses into his own self-understanding.

The first installment of this study will examine the religious trajectory of the life of Arnold Schoenberg. The second installment will focus on Kurt Weill and then draw conclusions regarding the variety of ways of being Jewish in the post-traditional West, as exemplified by the two composers.

Arnold Schoenberg

Choosing a Gentile Name

„Und da das Kind groß war, brachte sie es der Tochter Pharao, und es ward ihr Sohn, und sie hieß ihn Mose…“ „When the child grew up, she [his mother] brought him to Pharaoh’s daughter, who made him her son. She named him Moses.“ (Exodus 2:10)

„Und da sie zu ihrem Vater Reguel kamen, sprach er: Wie seid ihr heute so bald kommen? Sie sprachen: ein ägyptischer Mann errettete uns von den Hirten und schöpfte uns, und tränkte die Schafe.“ „When they returned to their father Reuel, he said, ‘How is it that you have come back so soon today?’ They answered, ‘An Egyptian rescued us from the shepherds; he even drew water for us and watered the flock.’” (Exodus 2:18-19)

„Und Mose bewilligte, bei dem Manne zu bleiben. Und er gab Mose seine Tochter Zippora“. „Moses consented to stay with the man, and he gave Moses his daughter Zipporah as wife.” (Exodus 2:21)

The narrative of the life of Moses begins with him receiving an Egyptian name. A few verses later, when he arrives in Midian, fleeing Pharaoh’s arrest warrant, and rescues the shepherd women from those who were molesting them, his dress and manner identify him as an Egyptian. He then marries one of those women, a daughter of the local pagan priest.

Arnold Schoenberg chose a non-Jewish identity for himself. At his birth, he had the dual secular and religious identity of Austrian Jews. In addition to the given name Arnold, his Hebrew name “Avraham” was recorded in the register of the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde of Vienna. But he converted to Lutheranism at age 24, in 1898. Three years later, in the same church where he had converted, he married his first wife, Mathilde, the sister of his music mentor and friend, Alexander von Zemlinsky. She, too, was a Jew by birth. She converted at the time of the wedding. Zemlinsky and his wife, Ida Guttmann, similarly, converted for their wedding in 1907. At about that time, Schoenberg wrote his only composition that clearly reflected a Christian outlook, his chorus “Friede auf Erden” (“Peace on Earth”), based on a Christmas poem by the Swiss poet and historical novelist, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer.[2]

In becoming Christian, Schoenberg was participating in a large wave of defections from Jewish life. Nine thousand Viennese Jews converted to Christianity between 1848 and 1903, with the peak year being 1898, the year of Schoenberg’s conversion.[3] The number of conversions was rising, in part, because of cultural assimilation, but also because of rising anti-Semitism.

Vienna was, indeed, the center of political anti-Semitism. In 1895, the Viennese elected Dr. Karl Lueger, head of the Christian Social Union, as mayor. Vienna was the first major city in Europe to take such a step. For Schoenberg, becoming a Lutheran meant (hopefully) leaving behind the disabilities of being Jewish in an anti-Semitic city.

Why Protestantism, in Roman Catholic Vienna? Schoenberg was within a minority of apostate Jews in opting for Protestantism, but he was hardly alone in that decision. In that time and place, half of the converting Jews became Roman Catholics, one quarter registered themselves as konfessionslos (non-denominational) and one quarter became Protestants. In Schoenberg’s case, personal influences were probably decisive. His friend, the tenor Walter Pieau, who sang the premier of Schoenberg’s song “Erwartung” in 1901, steered Schoenberg in that religious direction.[4]

Even so, there was a Jewish nuance to Schoenberg’s choice of Protestantism. Since Protestantism was rare in predominantly Roman Catholic Vienna, many of the people in the city’s Protestant circles were in fact Jews by birth. The enduring presence of former Jews in the Protestant community of Vienna suggests that Schoenberg still valued the national component that was one part of Jewishness. Baptism notwithstanding, a Jewish spark was not completely extinguished in Schoenberg.

Anti-Semitism would have kept this spark lit. In the terminology of the day, Jewish converts to Christianity were designated “baptized Jews” — baptized, but still, somehow, Jews. This reflects the ideology of racism, already current in German-speaking society by the last decades of the 19th century. The older, religiously framed prejudice of anti-Judaism had sought the conversion of the Jew. Once that goal had been achieved, the proselyte would be accepted as a fellow Christian. The newer ideology of racist hatred of the Jew, however, was not anti-Judaism but anti-Semitism. Wilhelm Marr, who coined the term, “anti-Semitism” and founded the Anti-Semiten Liga in 1879, was the first champion of this ideological change. In his best-selling prophecy of doom for the German nation, Der Weg zum Siege des Judenthums über das Germanentum, he charged that conversion could not end the Jewishness of the Jew.[5]

Here, too, the biblical story is suggestive: “She called his name Moses, ‘For from the water I drew him out’.” (Exodus 2:10). The Bible is straddling two languages here. It gives a Hebrew etymology for the word “Moshe”, connecting it to the Hebrew verb-stem m.sh.h., “to draw out”. Now, within the narrative logic of the Bible story, it makes no sense for Pharaoh’s daughter to name the child because of a Hebrew linguistic association. Surely, she thought in the Egyptian language, not in Hebrew. The Egyptian cognate of “moshe” means “the one who is born”, and therefore, “son”.[6] Similarly, “Ramesses” means “born of Ra”, the sun god, and “Thutmoses” means born of the god Thut. Naming the boy “Moshe” means that the Pharaoh’s daughter is claiming him as her son – and yet, within Biblical memory, the name reflects Hebrew, not Egyptian, etymology.

By analogy, even though Arnold Schoenberg was going through life with a European name and identity, he was not simply a comfortable member of the majority culture. He was a “baptized Jew”, with all the ambivalence and ambiguity suggested by that term. The activation of the residual Jewish potential within his identity, however, came in slow stages.

Gestation

„Zu den Zeiten, da Moses groß worden, ging er aus zu seinen Brüdern, und sah ihre Last“. „Some time after that, when Moses had grown up, he went out to his kinsfolk and witnessed their labors.” (Exodus 2:11) Moses was raised in the Pharaoh’s palace. The daughter of Pharaoh had claimed him as her son. So how did Moses know that the Hebrew slaves were his brothers? What seed of discontent drew him outside the charmed circle of assimilation?

Schoenberg did not reminisce or publish anecdotes about his Vienna years. But in examining the key events of his first decade of married life, it becomes clear that converting to Protestantism did not relieve him of the strain of feeling himself alienated in different ways. Making a living was difficult for him, made worse by the emotional loss he felt at the departure from Vienna in 1907 of his mentor and promoter, the conductor and composer, Gustav Mahler. Schoenberg took up painting in 1907, in part, to supplement his income, but with indifferent success. Mahler had given Schoenberg 800 kronen early in 1910, and then, later in the year, Mahler surreptitiously purchased one of Schoenberg’s paintings, concealing his identity so as to help his former disciple without impairing the latter’s dignity.

Schoenberg’s financial woes were compounded by personal crisis. In 1907, his wife had an extramarital affair with a neighbor, a member of their artistic circle, the painter Richard Gerstl. Arnold and Mathilde reunited in September 1908. Schoenberg dedicated his String Quartet #2 “To my wife”, but contentment was not at hand, because the premiere of the work, December 1908, was marred by rude behavior on the part of the audience and incomprehension by the learned music critics.[7]

These and similar reversals prompted Schoenberg to lash out at the Viennese in a 1909 essay, “About Music Criticism.” Schoenberg turned to the Bible (Genesis 18-19) for the literary image most damning to the Viennese: they were the men of Sodom and Gomorrah. But Sodom and Gomorrah were not spared God’s wrath, despite Abraham’s plea for clemency, because not even ten righteous men could be found therein; whereas Vienna endures. Schoenberg lamented the situation: “…it would almost be better were there not the few ’decent men’.” The unfortunate consequence of this reprieve is that the Viennese are shielded from the redemptive work of raising up a better culture.[8]

The comparison of the Viennese to the citizens of Sodom and Gomorrah is noteworthy on three counts. First, it shows that Schoenberg’s familiarity with the Hebrew Bible was already informing his thinking a full quarter century before his formal return to Judaism in 1933. Second, the quotation references Abraham’s negotiation with God. The choice of that biblical passage suggests Schoenberg’s identification with his biblical Hebrew namesake, for like Father Abraham, Schoenberg saw himself as a moral and prophetic voice. Third, and again following in the footsteps of Father Abraham, Schoenberg soon left his “native land and father’s house”, abandoning Vienna in 1911 for Munich and then Berlin, where he took up teaching at the Stern Conservatory. Relocation did not mellow him. Schoenberg nursed a sense of resentment against Vienna and turned down a teaching post at the Music Academy of Vienna when it was offered to him.

Spiritual Searching

„Er [Moses] aber sprach: So lass mich deine Herrlichkeit sehen. Und er sprach: Ich will vor deinem Angesicht her alle meine Güte gehen lassen… Und sprach weiter: Mein Angesicht kannst du nicht sehen; denn kein Mensch wird leben, der mich sieht. Und der HERR sprach weiter: Siehe, es ist ein Raum bei mir, da sollst du auf dem Fels stehen. Wenn denn nun meine Herrlichkeit vorüber gehet, will ich dich in der Felskluft lassen stehen, und meine Hand soll ob dir halten, bis ich vorüber gehe. Und wenn ich meine Hand von dir thue, du wirst mir hinter nachsehen; aber mein Angesicht kann man nicht sehen.“

“He [Moses] said, ‘Oh, let me behold Your Presence!’ And He [God] answered, ‘I will make all My goodness pass before you… ‘But, He said, ‘You cannot see My face, for man may not see Me and live.’ And the LORD said, ‘See, there is a place near Me. Station yourself on the rock and, as My Presence passes by, I will put you in the cleft of the rock and shield you with My hand until I have passed by. Then I will take My hand away and you will see My back, but My face must not be seen.’” (Exodus 33:18-23)

Moses is described in the Bible as the prophet who achieved the greatest communion with God ever experienced by mortal man (Deuteronomy 34:10). But even Moses was human, and hence unable to apprehend the reality of God perfectly. The human spiritual condition, even at its best, is one of yearning for an impossible fulfillment.

In 1912, Schoenberg wrote to his friend, the painter Vassily Kandinsky, that he was then contemplating writing an oratorio based on the Balzac novel Seraphita.[9] He did not do so, but in 1913, he composed the first in what would prove to be a long and important series of musical works expressing his spiritual yearnings: The Orchestral Song, op. 22, #1. His text was Stefan George’s German translation of the poem, “Seraphita” by the late-19th century English poet, Ernest Dowson.[10] The poem, in turn, is based on the Balzac novel. In both the novel and the poem, the character Seraphita is an androgynous, angelic being embodying the union of heart and mind.

Religiously, both the novel and the poem proceed from the mysticism of the 18th-century Swedish theologian, Emanuel Swedenborg. Schoenberg does not seem to have read Swedenborg, but from his reading of Balzac, Schoenberg was familiar with the description of the Afterlife elaborated in Swedenborg’s Heaven and Hell. At this stage of his religious journey, Schoenberg was much taken with the concept of Paradise as a place to which only the worthiest of souls are posthumously admitted, after having been refined over the course of many reincarnations. Like the angel of the novel, in touch with both the heavenly realms and the world of flesh and blood beings, Schoenberg saw the artist as that person most concerned to express the nexus of the spiritual and the material.

And yet, Schoenberg realized, this quest is inherently incapable of perfect fulfillment. Musical language is, ultimately, modeled on human emotions. But those emotions are inadequate to enter the precincts of a totally spiritual realm.[11]

Like Moses praying to God atop Mt. Sinai in Exodus 33, Schoenberg the artist considered himself standing at the threshold of an unearthly realm. In the words of another Stefan George poem that Schoenberg had earlier set to music in his String Quartet #2, “Ich fühle Luft von anderem Planeten” (“I feel air from another planet”). Musically, that new atmosphere meant that he filled the music he composed after 1908 with combinations of pitches unlimited by the traditional restrictions of tonality. In the five years between his composition of the String Quartet #2 and the completion of the first Orchestral Song, Op. 22 #1, he moved beyond the late-Romantic style of his earliest pieces and expressed himself in the sonic world of complete chromaticism, beyond the frontiers of his harmonic heritage.

While Schoenberg continued to write music outside the traditional limits of tonality for the rest of his life, in another respect, his Op. 22 #1 is nearly without a companion. He completed this work. That proved to be an exception for Schoenberg’s projects dealing with spiritual subjects. He ultimately left his most ambitious works on religious themes unfinished. His oratorio, Die Jakobsleiter, his opera, Moses und Aron and his “Modern Psalms” all exist only in torso.

Scholars speculate that there exists a common denominator in Schoenberg’s inability to finish precisely these pieces. Their subject matter dealt with the religious theme of the inadequacy of human thought to comprehend the infinity of God. Hence, the conjecture runs, these works express that theme by lapsing, unfinished, into silence.[12] On the other hand, there may be less abstruse reasons for his failure to complete each of those pieces. His war duty in the Austrian army severely hampered his ability to compose, temporarily extinguishing his musical voice in the middle of his work on Die Jakobsleiter. When he regained his compositional fluency, he was in a different place, religiously, as will be shown, so Die Jakobsleiter was no longer a compelling text for him.[13] In later chapters of his life, Schoenberg’s departure from Germany and exile from its linguistic and cultural life may account for his inability, despite his expressed desire, to write the music for the third act of Moses und Aron. His “Modern Psalms” may have been left unfinished for the most obvious reason—he was in poor health when he wrote their texts and died after having set only the first of the fifteen to music.

Die Jakobsleiter

„Und ihm träumete, und siehe, eine Leiter stund auf Erden, die rührete mit der Spitze an den Himmel, und siehe, die Engel Gottes stiegen daran auf und nieder.“ „He had a dream; a stairway [alt: “ramp”, others, “ladder”] was set on the ground and its top reached to the sky, and angels of God were going up and down on it.” (Genesis 28:12)

There is an immediate connection between Schoenberg’s orchestral song “Seraphita” and the oratorio, Die Jakobsleiter. In late 1912, Schoenberg sketched a few measures of the angel’s speech in the final chapter of the Balzac novel. The themes of that chapter include the metaphorical equivalence of melody, light, color, motion, and the creative Word. Schoenberg was fascinated by that topic. He exchanged ideas with Kandinsky on it. He also explored it in his orchestral work on colors (Farben, op. 16, #3).

In this analysis, melody, unfolding in time, is connected to mobility and hence to space. The angel of Balzac’s Seraphita explains that by means of this equivalence, angels can exceed all limits and be anywhere. Harmonically, exceeding all limits means crossing all boundaries of tonality, musical register, received traditions about instrumentation and all conventions about desired sonorities.[14] All of these extremes are explored in Schoenberg’s orchestral song and would continue to characterize his subsequent work—the first piece of which was Die Jakobsleiter.

The title is obviously a reference to the biblical story of Jacob’s ladder. This was not Schoenberg’s first intention, when he turned to the figure of the Biblical Patriarch. At first, he considered setting a portion of August Strindberg’s play, Jacob Wrestling, to music, either alone or in combination with Balzac’s Seraphita.[15] A fascination with the narrative of Jacob wrestling with God’s angel and wresting from him a blessing certainly conforms to Schoenberg’s spiritual state at the time. He was convinced that his path-finding way as a composer would consign him to soul-testing struggle, but that the artistic benefit he would produce for humankind would ultimately be a blessing.

Nonetheless, Schoenberg settled upon another image from the biblical Jacob saga, the image of the ladder in Jacob’s dream. Schoenberg substituted the image of the ladder as the central image of his work because it served his spiritual beliefs better. The ladder of the biblical narrative extends from earth to heaven. Schoenberg understood this in terms of what he deemed to be the central drama of human existence. He was especially concerned to convey the message that humans are on various steps towards perfection. To achieve that, the most important of goals, they need to dedicate themselves to the task of spiritual self-transformation.

This is the message of the main character of the libretto, the archangel Gabriel. Schoenberg himself began the libretto in 1915, broke it off while serving in the Austrian army, and completed it after his first discharge from army service in 1917. He turned to the music, but his recall to the army in September of that year ended his progress. Schoenberg’s text, earnest and didactic, serves as a window to his own spiritual state during the difficult years of World War I.

At the beginning of the text, an opening chorus represents the welter of humanity. The archangel Gabriel addresses the people, inviting forward those who believe that they have achieved progress towards salvation. Various groups, identified as the Dissatisfied, the Doubters, the Rejoicers, the Indifferent and the Resigned, come forward at Gabriel’s invitation. But, one by one, Gabriel refutes them. Gabriel approves only of the final human, known as The Chosen One. That person ascends to heaven — only to be reincarnated, to begin the next stage of still-higher ascent.

Mystical Judaism, the Kabbalah, contains the doctrine of reincarnation, but not in the specific form found in this work. Here, the plot device of the reincarnation of the partially perfected individual is borrowed from Balzac’s Seraphita, which, as has been shown, rests in turn on the religious teachings of Swedenborg. The idea of achieving ultimate salvation through a course of lifetimes did not originate there either. It is ultimately a borrowing from Hinduism. South Asian religious ideas had become increasingly well known in Europe starting in the early 19th century.[16]

Schoenberg completed setting about half of the libretto to music. He stopped before the second half of the text, in which Gabriel gives advice to humanity. The angel teaches people to set aside material concerns in favor of the spiritual. The angel’s advice includes the mandate to perform a central act of religious piety, as understood in many religions: People must learn to pray. The libretto closes with the combined prayers of the chorus of souls, both those in heaven and those now in the midst of their earthly sojourns.

Die Jakobsleiter reveals Schoenberg’s spiritual state at mid-life, during the crisis of the Great War. He was formally a Christian. Yet, alongside his professed faith, he contended with an added ambivalence stemming from the prejudicial conceit that converts from his ethnic background were in fact “baptized Jews”. Beyond the alternatives of Christian and Jew, his religious approach was eclectic. A religious syncretist, he combined Jewish and Christian motifs with those of South Asian religion, most likely absorbed second-hand through his reading of Balzac and Rudolf Steiner. He attempted to marshal these various traditions to fashion a way forward at a time when humans were engaged in unparalleled, wholesale self-destruction. Within half a decade, this would change.

Return to the Covenant: (1) Return to his People

„Lange Zeit aber danach […] seufzeten [die Kinder Israel] über ihre Arbeit und schrieen, und ihr Schreien über ihre Arbeit kam vor Gott. Und Gott erhörete ihr Wehklagen und gedachte an seinen Bund mit Abraham, Isaak und Jakob. Und er sah drein, und nahm sich ihrer an.” “A long time after that… the Israelites were groaning under their bondage and cried out; and their cry for help from the bondage rose up to God. God heard their moaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac and Jacob. God looked upon the Israelites, and God took notice of them.” (Exodus 2:23-25)

The Biblical narrative of the Exodus contains a sober, pragmatic reflection on the relationship of God and the Jewish people. The long duration of the Israelite enslavement was an uncontestable part of Israelite historical memory. Why did God take so long? Exodus 2 offers a theological response: their liberation only happened once the Israelites “groaned from their bondage.” Their outcry was the trigger for Redemption.

In Schoenberg’s case, the outcry happened in 1921, when he came face to face with anti-Semitism in a most personal way. The effect of this encounter upon Schoenberg was profound and lifelong. True, he never disavowed a concern for suffering humanity as a whole. But after 1921, he focused increasingly on working for the Jewish nation. Schoenberg also reengaged with the Jewish tradition as his exclusive spiritual resource, working his way towards a distinctive interpretation of Judaism, especially of the message of the Bible.

The 1921 incident could, at first glance, have been construed as a petty social snub, although Schoenberg saw the matter quite differently: One of the aspects of the climate of growing anti-Semitism in post-World War I Austria was segregationist pressure. Christians vacationing in their favored watering holes wanted Jews excluded. One such establishment was the Salzburg region’s lakeside resort at Mattsee. By 1921, Schoenberg had spent his summer vacations there for half a decade, bringing with him an intimate circle of family and close students. But that summer, resort officials informed him that a local governmental edict now required guests to provide proof that they were Christians.[17] Of course, they explained, he was certainly welcome, if he would only produce his baptismal certificate. Rather than doing so, Schoenberg left Mattsee, taking his entourage with him.

Why was the 1921 incident the turning point? This was not his first encounter with anti-Semitism. There was no way to avoid reminders of the pervasive anti-Semitism of Austrian society. For example: in 1915, Schoenberg was in Vienna to conduct the Mahler orchestration of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Rehearsals did not go well; as a result, the performance was below professional standards. But the concert review published in the Ostdeutsche Rundschau went beyond music criticism. The reviewer chided Schoenberg for failing utterly to penetrate “into the lofty spirit of this eternal monument to Germany’s cultural greatness.”[18] This anti-Semitic aside was an echo of Wilhelm Marr’s racist typology of Aryan versus Semite. In that construct, the Aryan is the true cultural creator, the Semite, a plagiarist. The Aryan ennobles; the Semite perverts.[19] This is the same charge that, a decade later, would be one of the main messages of Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

It is worth pondering why not earlier incidents, but rather the confrontation in Mattsee, occasioned a paradigm shift in Schoenberg’s worldview. Given Schoenberg’s temperament, perhaps the personal assault on his dignity was what he found insufferable. His decision to pack up and leave for another resort, rather than send for his documentation and get on with his vacation, is reminiscent of his 1911 departure from his native city. At that time, an irate neighbor had accused Schoenberg of failing to prevent his pre-teen daughter from making an inappropriate advance towards the neighbor’s son. Schoenberg could have opted for a measured response to that strictly domestic matter, or even found a more congenial residence elsewhere in Vienna. But he regarded that insult as a final straw and uprooted. Here, too, Schoenberg chose decisiveness rather than diplomacy. He had a pugnacious side, sharpened by the whetting action of constant critical rejection.

Schoenberg certainly drew far-reaching conclusions from the incident. It brought home to him that, in a racist society, the status of “baptized Jew” was really no different than “Jew”. In that case, he would live with that reality, and not delude himself in fantasies of toleration. That is how he framed it in a letter to Kandinsky in 1923: “Was ich im letzten Jahr zu lernen gezwungen wurde, habe ich nun endlich kapiert, und werde es nicht wiedervergessen. Dass ich nämlich kein Deutscher, kein Europäer, ja vielleicht kaum ein Mensch bin (wenigstens ziehen die Europäer die schlechtesten ihrer Rasse mir vor) sondern, dass ich Jude bin.” “What I was forced to learn during the past year, I have now at last understood and shall never forget it again: namely, that I am no German, no European, maybe not even ein Mensch—at any rate the Europeans prefer the worst of their own race to me—but that I am a Jew. I am satisfied with this state of affairs. Today I do not wish to be treated any longer as an exception.”[20]

The letter expresses strongly a change in Schoenberg’s self-image. To understand that change, it is helpful to explicate the context of this exchange of correspondence. Once close colleagues, Schoenberg and Kandinsky had been parted by the World War and only reconnected in 1922. Kandinsky, then teaching at the Bauhaus school in Weimar, invited Schoenberg to become the Director of Music at that avant-garde institution. Schoenberg had heard rumors that the school was home to an anti-Semitic circle, and questioned Kandinsky about it. Kandinsky’s reply confirmed Schoenberg’s suspicions. Kandinsky was willing to see Schoenberg as the exception, the “good Jew” rising to a higher ethical level than the mass of his fellow Jews. Schoenberg would have none of it.

It is possible that at first, Schoenberg thought about the rebuff he had received in more local terms, and only later came to the conclusion that it was of a more general significance. After leaving Mattsee, he went to another resort, Traunkirchen, where he enjoyed a productive summer. He returned to Traunkirchen the next year, and among other activities that summer, he arranged a charity concert to raise funds to pay for new church-bells for the local church.[21] Perhaps he was merely being a good neighbor or expressing his gratitude that he was accepted without quibbles in Traunkirchen—or perhaps he had not yet reached the point in his thinking expressed in his 1923 letters.

But in any case, either right away or upon reflection, Schoenberg confronted the possibility that the rebuff delivered by the resort officials in Mattsee might in fact be the leading edge of a much more dangerous development. If Jews were not welcome in a resort today, where would they be unwelcomed tomorrow? When would they be unwelcomed in any place where they were a minority?

While such a leap would have seemed hyperbolic to most observers prior to the advent of the Nazis, it is clear that Schoenberg was quite concerned about the direction in which growing anti-Semitism was likely to lead. This concern is apparent in a subsequent letter he sent Kandinsky. In an anguished message, written on May 4, 1923, Schoenberg tried to make his fellow artist understand what was ultimately at stake: “what is anti-Semitism to lead to if not to acts of violence?” [22]

If violence was in the offing, would it be possible to defend against it? If not, how was escape possible? In what place on earth would Jews be allowed to live and be themselves?

An Unconventional Zionist

„Um Zions willen will ich nicht schweigen, und um Jerusalems willen will ich nicht innehalten, bis seine Gerechtigkeit aufgehe wie ein Glanz und sein Heil brenne wie eine Fackel, dass die Völker sehen deine Gerechtigkeit und alle Könige deine Herrlichkeit.“

For the sake of Zion, I will not be silent,

For the sake of Jerusalem, I will not be still,

Till her victory emerge resplendent

And her triumph like a flaming torch.

Nations shall see your victory,

And every king your majesty. (Isaiah 62:1-2)

At the time of the composition of the final chapters of Isaiah, Jerusalem had been destroyed by the Babylonian army. The prophet, addressing the Judean exiles in Babylon, or perhaps the first few pioneers to have returned to Jerusalem, expressed his passionate concern for its rebuilding and its return to glory as the center of Jewish life. While Zionism, in its political sense, is a modern development, its attitudinal foundation is already evident in these biblical sentiments.

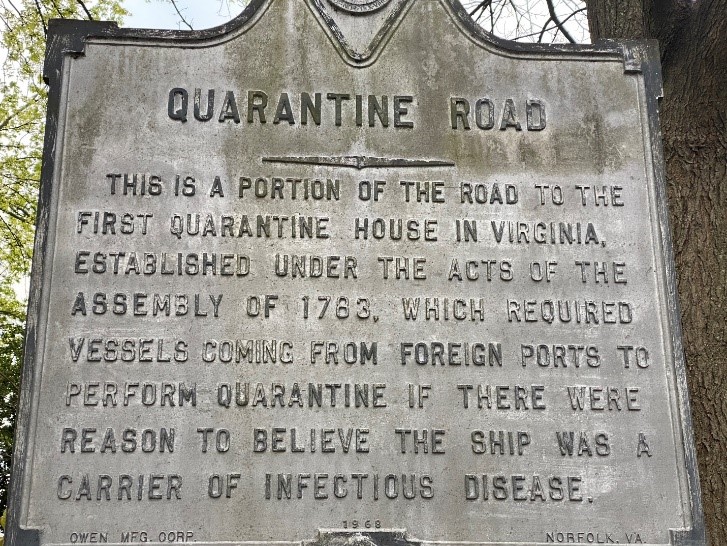

The first result of Schoenberg’s reengagement with his identity as a Jew was his turn to Zionism. The connection between anti-Semitism and Zionism for Schoenberg is quite clear. Schoenberg saw, earlier than most of his contemporaries, that the petty apartheid of local Austrian anti-Jewish ordinances and the racist fantasies of music critics were not merely the actions of a trailing edge of reactionaries. The growing anti-Semitism of the post-World War I world, he recognized, was part of a larger and growing eruption of hatred. This hatred could indeed lead to violence, indeed, to genocide. Preventing it might not even be possible, so escaping it became the imperative of the generation—hence, the exploration of Zionism, with its program of rescuing the Jewish People by securing its return to its historic homeland.

Zionism was a synthesis of the old and the new. The trigger for the transformation of the age-old yearnings of Jews to return to the Land of Israel into a modern, western-style political movement was the dawning realization that Emancipation was not leading to a society free of anti-Semitism. In fact, the more Jews successfully integrated themselves into Western and Central European states, it seemed, the more anti-Semitism grew. Was anti-Semitism somehow an inescapable part of this process?

That radical conclusion was first formulated by an assimilated Jewish journalist from Budapest, Theodore Herzl. As the Paris correspondent of a Viennese newspaper, Die Neue Freie Presse, he covered the trial of Alfred Dreyfus and its aftermath in the mid- 1890’s. Dreyfus, a French Jewish army officer, was falsely accused of selling military secrets to Germany. His trial, degradation and imprisonment were gross miscarriages of justice. Public debate over the case continued for a decade. The “Anti-Dreyfusards” of the day engaged in a large-scale upsurge of virulent anti-Semitism throughout France. Appalled that the hatred of the Jew was on the rise in the one country, France, where Jews had enjoyed Emancipation for a full century, Herzl concluded that the only way to shield world Jewry from anti-Semitism was for Jews to leave the Diaspora and create an independent Jewish state, preferably in the historic Jewish homeland, Israel.

Herzl’s Zionist manifesto was anathema to the Jewish establishment throughout Central and Western Europe. Prior to the rise of Nazism, most westernized Jews rejected Zionism. That was because the most basic—if often-unspoken— quid pro quo for the improvement of Jewish civic status in 19th century Europe was the privatization of Judaism. It would henceforth be a religion, a denominational confession, as Protestantism was thought to be. A Jew could profess his religious beliefs in the vocabulary of his tradition, and yet be a patriotic Austrian, German, French or English citizen. But he could not proclaim his membership in the Jewish nation without imperiling the Emancipation he was just coming to enjoy as a member of any of the various European nations. Zionism was a proclamation of Jewish nationalism. As such, it seemed to imperil the entire basis of Jewish existence in the still-intolerant world of early 20th-century European nation-states.

Schoenberg came to Zionism because, like Herzl, he thought that Jews were deluding themselves in the belief that their growing integration into European society would cause anti-Semitism to wane. Schoenberg feared that the consequences of anti-Semitism could grow to deadly proportions within a short period of time. All this was before Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch. Perhaps Schoenberg was more prescient than his contemporaries because of his unconventional temperament and worldview. How he arrived at his dark imaginings is not fully explicable; that he was correct is sadly all too true.

After 1933, once Schoenberg reached a safe haven in the United States of America, he made political advocacy on behalf of the realization of the Zionist dream a personal priority. In the 1920’s, though, he channeled his regained sense of being Jewish into his work as a creative artist. He renewed his engagement with the Hebrew Bible, starting work on a cantata dealing with the biblical narrative of Moses at the Burning Bush. He did not finish that cantata, but in 1925, he composed the first fruits of this engagement, his opus 27 #2, the choral piece “Du sollst nicht… du musst.” That did not exhaust Schoenberg’s interest in Jewish themes. In 1926-1927, he wrote a play on Zionist themes, Der biblische Weg. Then, in 1928-1930, he composed one of his most ambitious and significant works, the opera Moses und Aron.[23]

Der biblische Weg (The Biblical Way): A dark Zionist fantasy

„Mose schrie zum HERRN und sprach: Wie soll ich mit dem Volk thun? Es fehlt nicht weit sie werden mich noch steinigen.“ „Moses cried out to the LORD: ‚What shall I do with this people? Before long they will be stoning me!’” (Exodus 17:4)

The biblical Moses expressed the fear that, driven mad by thirst, the Israelites would murder him. This theme has resonated in biblical explorations on the part of 20th century thinkers. It figures as the central event of Sigmund Freud’s 1939 Moses and Monotheism. Schoenberg, Freud’s Austrian-Jewish contemporary, likewise speculated on the murder of Moses. In Freud’s telling, the murder was in the formative stage of the existence of the Jewish people. In Schoenberg’s telling, though, the murder happens in the fictional present.

Despite its archaic sounding title, Der biblische Weg is an alternate history set in Schoenberg’s own time. Its kernel of historical inspiration was a plan devised by Theodore Herzl in 1903 for the settlement of the Jews in the British colonial territory of Uganda. Herzl had been frustrated by his inability to negotiate an agreement with the Ottoman Sultan to concede an autonomous region for the Jews in Palestine. In Russia, after a 20-year hiatus, anti-Jewish pogroms had resumed in 1903. Eager to secure a safe refuge for the Jews, Herzl met with the British colonial secretary, Joseph Chamberlain, who offered an area in East Africa for Jewish settlement. Herzl urged the Zionist executive to accept a revision of Zionist goals. He advocated an immediate colonization of Uganda. He characterized it as a temporary refuge, a Nachtasyl. His plan carried by a slim majority, but Herzl died soon after and the plan failed to materialize.

Schoenberg offered a verdict on that turn of history. In his play, Schoenberg explored what might have happened had a Jewish colony actually been established in Africa, to serve as a waystation on their way to their ultimate homeland.

As suggested by its title, Der biblische Weg is actually a meditation on the Bible, understood as the master story, i.e. the identity-forming narrative, of the Jewish people. For his portrayal of the fictional leader of the colony, Max Aruns, Schoenberg drew upon the biblical image of Moses, leading the Israelites through the Wilderness towards the Promised Land. In the play, the characters made repeated references to the Bible. The character of Aruns invokes Moses as his leadership model. Other characters in the play, likewise, seek to apply biblical precedents to their situation, but draw different lessons. Their contrasting applications of the same biblical tales underscore the dramatic conflict between Aruns and his critics. Again, like Moses, Aruns faces the murderous wrath of the people; but unlike Moses, Aruns is indeed murdered by the mob. While he dies, a successor emerges, “Guido”. Here too, Schoenberg echoes a biblical typology. Guido is to Max Aruns as Joshua was to Moses in the biblical narrative: a successful successor, leading the Israelites to military victory.

While Schoenberg completed Der biblische Weg before he made significant progress on his opera, Moses und Aron, he began thinking about both projects at the same time, in the mid-1920’s. So, it is not surprising that, at key points, the ideas Schoenberg developed in this play were to reappear in the opera. In particular, the notion that there is a necessary tension between Moses and Aaron became the main conflict of the opera. This theme is sounded in the play by Aruns’ chief opponent, David Asseino. Asseino criticizes Aruns for attempting to fuse the roles of both Moses and Aaron in his own person. Aruns should have reflected more humbly on why God had seen fit to separate those two embodiments of leadership: “Moses, to whom God granted the idea and who renounced the power of speech; and Aron, who could not grasp the idea, but who could reproduce it and move the masses.”

The resemblance between play and opera includes specific turns of phrase. The dying Aruns invokes God as one, eternal, and beyond any representation, words that Moses echoes in the beginning of the opera.[24] Der biblische Weg offers valuable insights into the state of Schoenberg’s religious thinking in the mid-1920’s. He replaced the wide-ranging syncretism of his earlier works with a more exclusive engagement with the Bible. In particular, he responded to the story of the Israelite journey from slavery, through wilderness, and towards their Promised Land as a typology, whose truth could be repeated in the present day.

His theology, too, showed new features. Schoenberg was now concerned to portray God as the “Holy Other”, in sharp contrast to all that is finite. Intriguingly, Schoenberg’s understanding of God bears comparison with that of his contemporary, Rudolf Otto, a highly influential German scholar of religion. Otto’s most important work, Das Heilige: Über das Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein Verhältnis zum Rationalen, (title in translation: The Idea of the Holy) dates to 1917. Immediately popular, its ideas would have been in the air when Schoenberg developed his mature theology. Otto stresses that the Liberal Theology of the 19th-century often reduced God to ethics, and in so doing, failed to capture something essential about God. Otto labeled that essence “The Numinous”. Similarly, Schoenberg sounded the theme of God’s otherness. We are finite; God is not. We are ephemeral; God is eternal. We are compounded of material and spiritual aspects; God is a pure unity.

Schoenberg failed to bring his play to the stage. He invited the leading German impresario and theater director, Max Reinhardt, to stage it, but Reinhardt declined. Consequently, the ideas that Schoenberg developed in Der Biblische Weg did not have a public impact, presented in that form. Nonetheless, at the same time, he composed musical pieces that successfully entered the canon of twentieth-century classical music. These pieces dealt with much the same theological idea.

Return to the Covenant: (2) Return to his People’s God. The Second Commandment

„Und ihr sollt mein Volk sein, und ich will euer Gott sein.“ „You shall be My people/ And I shall be your God”. (Jeremiah 30:22)

„Du sollst dir kein Bildnis noch irgend ein Gleichniss machen, weder dess, das oben im Himmel, noch von dess, das unten auf Erden, oder dess, das im Wasser unter der Erde ist: Bete sie nicht an und diene ihnen nicht!“ You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image, or any likeness of what is in the heavens above, or on the earth below, or in the waters under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them. (Exodus 20:4-5)

Monotheism is the most revolutionary feature of the Bible. In paganism, the worshiper may venerate one deity particularly, but even so, respect for all the gods is a given. There is no warrant for the worship of one god and no others. Only in the Bible does God demand that the Israelites maintain an exclusive relationship with their deity. The prohibition against idolatry is biblical religion at its most characteristic.

Schoenberg was profoundly engaged by the biblical prohibition against idolatry. He formulated a sophisticated understanding of that commandment, expressing it in both text and music. In a letter to Alban Berg, Oct. 1, 1933, Schoenberg cited his choral piece, “Du sollst dir kein Bild machen,” written in 1925, as evidence that he had not reconverted to Judaism only recently, but rather that he was already back in the Jewish fold “long ago”.[25]

Schoenberg himself wrote the text:

Du sollst dir kein Bild machen!

Denn ein Bild schränkt ein

begrenzt, fasst,

was unbegrenzt und unvorstellbar bleiben soll.Ein Bild will Namen haben:

Du kannst ihn nur vom Kleinen nehmen;

Du sollst das Kleine nicht verehren!Du musst an den Geist glauben!

unmittelbar, Gefühllos und selbstlos.

du musst, Auserwählter, musst, willst du’s bleiben![26]

In its own day, the Bible’s commandment against the worship of false gods referred to the role of idols, concrete representations of the gods, in the religions of the Ancient Near East. But the concept of idolatry is not limited to the physical idols of the neighbors of the ancient Israelites. The main theological message of the Bible is that God is the One God; nothing else can compare. Therefore, idolatry could be understood as the worship of anything that is not God in the place of God.

Schoenberg constructed his own theology in the light of this Biblical theme. What is prohibited under the rubric of idolatry is anything that humans improperly elevate to the status of the Divine. This is a sweeping application of the biblical prohibition. Humans are finite. If they can fully name something, it is only because the finiteness of the object of their thought is commensurate with the finiteness of their thought itself. Hence, whatever can be named, or pictured, or grasped, is not truly God.

Theologically considered, Schoenberg’s interpretation of the commandment against idolatry echoes the main current of traditional rabbinic thought. The most influential rabbinic theologian of the Middle Ages, Rabbi Moses Maimonides, stressed that human language is inadequate to describe God. For example, to say that “God is good” implies a definition of what “good” means. But that definition itself is limited to our range of experiences. As such, it partakes of our finite understanding, and thus fails to describe God accurately. Maimonides would accept as strictly true theological declarations only negative statements, such as “God is in no way evil.”

That is not to say that Schoenberg immersed himself in post-biblical Jewish studies. His assertion of monotheism came from its own starting point in European culture. Like his modernist contemporaries, he was contemptuous of the materialism of western society. But unlike many modernists, he was not drawn to the surrogate messianism of Marxism. Instead of secularizing the concepts of religion, he reinvested them with power to speak to his own day. He saw a world being torn apart by people in the grip of base emotions. In the language of his theology, they were worshipping their own tribalism, their own drives for power and domination, even their own intellect. They were guilty of venerating something no higher than themselves. Schoenberg surveyed the course of his own generation’s history—world war, devastation on an unprecedented scale, followed by the giddy pursuit of unworthy goals—and he condemned it as idolatry. He used biblical language to speak to his own day.

Moses und Aron

„Und da Aaron, und alle Kinder Israel sahen, dass sie Haut seines Angesichts glänzete; fürchteten sie sich zu ihm zu nahen. Da rief ihnen Mose; und sie wandten sich zu ihm, beide Aaron und alle Obersten der Gemeinde, und er redete mit ihnen.“ „Aaron and all the Israelites saw that the skin of Moses’ face was radiant; and they shrank from coming near him. But Moses called to them, and Aaron and all the chieftains in the assembly returned to him, and Moses spoke to them.” (Exodus 34:30-31)

The biblical narrative of the prolonged encounter between Moses and God atop Mt. Sinai concludes with an account of the transfiguration of Moses. His skin shone. The effect frightened the Israelites. Moses wore a veil ever after, removing it only when he was conveying God’s instructions to them, or when he was alone in communion with God. (Exodus 34:33-35).

The text suggests that the close communion with God made Moses seem alien to his fellow Israelites. That is the point of departure for Schoenberg’s meditation on the consequences of fully rejecting idolatry and cleaving to God.

After completing Der biblische Weg and “Du sollst nicht…du musst”, Schoenberg continued to focus his creative energies on presenting the ideas explored in those works. The result is his largest-scale work expressive of his religious standpoint, the opera Moses und Aron.[27] It occupied the largest part of his composing efforts from 1928 to 1930. He completed the entire libretto and the music for two of its three acts.

Schoenberg never learned Hebrew. He read the Bible in Luther’s translation. Schoenberg originally intended to use biblical excerpts as the libretto for the opera, but he ultimately rejected that in favor of supplying his own text. He explained his decision in a letter to Alban Berg, written August 5, 1930: he rejected the idea of using the Bible’s own words because they are “medieval German.”

Schoenberg did not further explain himself on this point, but three plausible explanations of his decision may well have coexisted in his mind. First, while Luther’s translation has enjoyed high status through the centuries, by the second quarter of the twentieth century, it was increasingly perceived to be archaic. This is analogous to the debate in Anglican circles from the same era on updating the language of the 17th century King James Version and Book of Common Prayer. Second, by the time he wrote the libretto to Moses und Aron, Schoenberg was well along the road of reaffirming his Judaism, and while Luther’s text remained his channel to the Bible, its Christian orientation no longer served Schoenberg well. Most likely, I would argue, the biblical narrative did not supply the exact words needed for the theological ideas Schoenberg wished to expound in his retelling of the story. He needed his own words, to express precisely what he wanted to convey about the difficult mandate of monotheism.

Schoenberg’s willingness to modify the traditional text considerably is apparent in many details of the libretto. One characteristic example is his reworking of the story of Moses striking the rock at Meribah to produce water for the thirsty Israelites. In a 1933 letter to Walter Eidlitz, Schoenberg noted that the story of Moses striking the rock is found twice, in Exodus 17 and in Numbers 20, but that the contradictions between the two accounts render the Biblical narrative incomprehensible. Religious traditionalists throughout the ages have harmonized the differences between the two narratives by claiming that the Bible is speaking of two different events. Schoenberg rejected that apologetic argument. Although there is no evidence that Schoenberg studied the writings of academic Bible scholars, in this instance, his conclusion was in line with the consensus of critical opinion, that the Bible preserves two divergent traditions concerning one incident rather than memories of two incidents. But unlike the academic Bible scholars, Schoenberg drew his own, independent conclusion from this insight. He reassigned the miracle to Aaron.

In fact, throughout his libretto, Schoenberg’s retelling is quite a free adaptation of the biblical narrative. In its very first line, it introduces a striking change in the characterization of Moses. Whereas in the Bible itself, God calls to Moses at the Burning Bush, in Schoenberg’s version, Moses calls to God. Moreover, Moses is already a theological sophisticate. The opera opens with Moses invoking God in terms familiar from the language of “Du sollst… du musst”. Moses identifies God as “Einziger, ewiger, allgegenwärtiger, unsichtbarer und unvorstellbarer Gott” (“One eternal, omnipresent, invisible, and unrepresentable God”).

Innovativeness characterizes the music no less than the libretto. God’s response to Moses in the opening scene is a case in point. Schoenberg represents the voice of God by a chorus of six voices. This contains a significant theological point, expressed musically. The rich tradition of classical religious music to which Schoenberg was heir often portrayed God as a solo baritone. A striking example is J.S. Bach’s 1731 church cantata Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme. One of the movements of that cantata is a love duet between Jesus and the soul. The soprano, voicing the soul’s spiritual love, asks Jesus: “Wann kommst du, mein Heil?” (When are you coming, my Savior?) to which he sings the reply, “Ich komme, dein Teil”. (I, thy portion, am coming). Bach’s music is lyrical, even ravishing, portraying the intimacy of God and the soul.

Schoenberg’s choice for the representation of God’s voice is a striking departure from the established musical tradition. Schoenberg rejected such images as are conveyed in that tradition as sentimentality. God is a commanding presence because God is holy; and God is holy precisely because God is not an accessible, easily emulated role model. Quite the contrary: God is wholly other than the unsophisticated norm of human thinking and acting—and the music ought to convey the otherness of the divine.

Hence, Schoenberg depicted the voice of God by a chorus rather than a solo. This is how he indicated that no single human voice is adequate to convey God’s words. Since God is, in the terms of the Mosaic invocation, unvorstellbar, the attempt to represent God’s voice by the human voice is doomed to failure. Now, the medium of opera demands that voices be used. But Schoenberg employs a chorus, to produce sounds that no individual person could possibly produce, to convey the infinite essence of God.

One might object: is not a chorus, too, ultimately a set of human voices? Has Schoenberg merely relocated the problem, rather than solved it? How does one convey in words the concept that words are inadequate to describe the reality of the infinite, of God, and that the human vocation needs to be a response to that insight?

In fact, that dilemma becomes the central dramatic issue of Moses und Aron. Moses represents the ideal prophet. He understands that God is beyond human ken. In that, he stands closest to the ideal. But that insight is, at some level, incapable of expression. The very act of putting it into words is already half a betrayal.

This issue leads Schoenberg to assign a great interpretive weight to the words of Moses at the Burning Bush in the original Biblical narrative. There, resisting God’s commission, Moses protests his inadequacy to speak to Pharaoh: „Ach, mein Herr, ich bin je und je nicht wohlberedt gewesen…denn ich habe eine schwere Sprache, und eine schwere Zunge.” ” Please, O LORD, I have never been a man of words… I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.” (Exodus 4:10)

In the original context, the meaning of that verse is that Moses is not eloquent. Rabbinic tradition read the verse hyper-literally and elaborated a side-bar story to explain how Moses developed a speech defect when he was yet a baby.[28] For Schoenberg, neither the literal meaning of the Bible nor the rabbinic commentaries suffice to convey the meaning of Moses’ difficulty. Rather, the inability of Moses to communicate is neither happenstance nor the result of an early trauma. On the contrary, it is inherent in the success achieved by Moses in communing with the image-less, inconceivable God. There simply are no words for that. Musically, Schoenberg underscored that textual message by having Moses half-speak, half sing, in the Sprechstimme style that Schoenberg had earlier developed. There is only one place in the opera where Schoenberg indicated that Moses might break out into song, when he exhorts the Israelites: “Purify your thinking/ Free it from worthless things/ Let it be righteous.” But this is from the third act of the libretto, which Schoenberg did not set to music, so there is no knowing what song might have dressed these words.[29]

Hence, Moses needs Aaron, skilled in communication, to help bridge the gap of understanding between Moses and the people. But success is impossible here as well. The very fluency of Aaron, expressed musically in the soaring melodic lines Schoenberg assigned to his part, is a betrayal of the austere truth of Moses’ message. The result is a predictable tragedy. When Moses is atop Mt. Sinai, receiving the Tablets of the Law, and hence is not physically present, the desire of the Israelites to have a tangible representation of their god overcomes the prohibition against idolatry they have just heard. In his absence, the Israelites and Aaron construct and worship the Golden Calf.

Again, Schoenberg’s treatment of the biblical narrative is free. In the Bible, the people, fearing that Moses is gone forever, clamor for Aaron to fashion for them a god to lead them (Exodus 32:1). Aaron plays for time, but ultimately complies. When Moses returns, he shatters the Tablets, a sign that the Israelites have broken the covenant. He destroys the idol and remonstrates with Aaron. In reply, Aaron pleads that the people forced his hand. But in Schoenberg’s retelling, Aaron justifies the construction of the Golden Calf. He argues that is impossible to make the idea of God comprehensible without some form of representation. The idol is a means to a worthy end. When Moses insists that Aaron not give up on the vehicle of purely abstract thought as the only true way to God, Aaron has a surprising rejoinder: Are not the Tablets of the Law that Moses is then holding also an image? That epiphany is why Moses shatters the Tablets. Thereupon, a pillar of fire appears, a divine miracle, and this turns the Israelites back to the worship of God. But it is not enough for Moses, because the pillar of fire, too, is an apparition, an image. He cries in despair,

Unvorstellbarer Gott!

Unaussprechlicher, vieldeutiger Gedanke!…

Läßt du diese Auslegung zu?

Darf Aron, mein Mund, dieses Bild machen?

So habe ich mir ein Bild gemacht, falsch,

wie ein Bild nur sein kann!

So bin ich geschlagen!

So war alles Wahnsinn, was ich

gedacht habe,

und kann und darf nicht gesagt werden.

“Unimaginable God, inexpressive thought of many meanings!… So, I am defeated! So, everything I thought was madness and cannot and must not be spoken.” Moses concludes his lament thematically: “O Wort, du Wort, das mir fehlt!” (“O word, thou word, that I lack!”) (Act II, Scene 5).

Thus, at the end of Act II of Moses und Aron, the central theological problem still seems insurmountable. God and humans are not commensurate. God’s thoughts are not human thoughts. Consequently, even God’s miracles, such as the pillar of fire, are misunderstood, and even God’s works become conducive to idolatry. Moses has a unique insight into God, but being human, he lacks the means of conveying that insight in all its language-transcending profundity. Aaron the compromiser, Aaron the betrayer of the pure idea, has the upper hand.

Schoenberg resolves this dilemma in Act III, which departs the most from the biblical original. Aaron enters in chains. Moses is judging him on the charge of having enslaved the people to material things. As part of the indictment, Moses cites the miracle that Aaron had wrought, striking the rock and producing water. This is culpable because it induced the people, again, to believe in false gods, gods who can be pictured. Moses pronounces him guilty, but nonetheless sets him free; whereupon Aaron dies. In essence, Aaron suffers the same fate as the Golden Calf he created. When Moses saw the idol, he made it disappear with a word: “Begone, you image of powerlessness, you enclose the boundless in an image!” — Whereupon the idol simply vanished. Aaron’s death is comparable: another miraculous demonstration of the power of the Infinite over the finite, “das Kleine.” Aaron’s ideals are earthly and mortal, and his death demonstrates the insufficiency of his theology.

Moses has the last word. He tells the people that they will continue to dwell in the Wilderness, where they will succeed in emancipating themselves from the worship of the finite, the image-bound, the material. In the Wilderness, they will unite with God. This closing charge sounds the theme of the destiny of the Jewish people. In this, it echoes the last line of the earlier composition Du sollst nicht… du musst. For the Jews, their status as Chosen People is bound up with their true worship of spirit alone. In the desert, apart from the allure of material civilization, from “the fleshpots of Egypt,” the Israelites can fulfill their mandate to be a Holy People.[30]

Schoenberg completed this much of the opera by 1930. He attempted to finish Moses und Aron in 1932. Shortly thereafter, Hitler came to power and Schoenberg was dismissed from his musical post. In early 1933, Schoenberg left the personal Egypt of Nazi Germany and traveled to the United States, which for him was more Wilderness than Promised Land. In the United States, moreover, Schoenberg’s religious development continued. Like the Israelites in the Wilderness, according to the final scene of Moses und Aron, Schoenberg, while in America, sought his own communion with God, in new language.

Return to the Covenant (3): Schoenberg the Jew

„Höre, Israel, der HERR ist unser Gott, der HERR ist ein einiger Herr.“ „Hear, O Israel: The LORD is our God, the LORD alone” [ alternately: “is One”].(Deuteronomy 6:4) The liturgical climax of a ceremony of conversion to Judaism is when the proselyte recites the “Shema Yisrael” prayer: “Hear, O Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD is one.”

Leaving Germany in May 1933, Schoenberg’s first stop was Paris. On July 24, 1933, he visited the Rue Copernic Synagogue of the Union Libérale Israélite de France, where he formally reconverted to Judaism.[31] In so doing, he was performing an act that was not required under Jewish religious law. The Jewish religion does not, in fact, mandate that its adherents who had professed another faith undergo a ceremony of conversion when they return to the fold. But the formalization of his identity was necessary for Schoenberg, psychologically. He had fled Germany because he was a Jew. The process begun at Mattsee in 1921 was now complete.

The ceremony included a staple of Jewish formal procedure for such matters. Schoenberg made his profession of faith before a panel of three. Presiding over the panel was Rabbi Louis Germain Levy, the rabbi of the congregation. The two other witnesses were the painter Marc Chagall and the stepson-in-law of Albert Einstein, David Marianoff. The selection of Chagall is intriguing. By 1933, that artist was already well known for his Jewish-themed art. He had spent time in the Land of Israel and drawn inspiration from his experience there. Upon his return to Paris, Chagall began a series of biblical illustrations.

I offer the surmise that Schoenberg approached Chagall because he was still wounded by the rupture of his close relationship with Kandinsky. As recounted earlier, at first Schoenberg and Kandinsky were friends and artistic fellow-travelers. But when Schoenberg learned that Kandinsky harbored anti-Semitic attitudes, he broke off their relationship. Chagall was a modernist painter, a virtuoso with color, but also a proud Jew. Chagall, I imagine, represented the antithesis of Kandinsky in Schoenberg’s thinking.

What kind of a Jew was Schoenberg? He did not fit into any of the standard denominations of modern, western Judaism. It must be acknowledged that his Judaism was not a matter of religious practice. He did not learn Hebrew, even though he later composed music with Hebrew texts. He declined invitations to attend Reform Jewish synagogue services, citing his ignorance of both the Hebrew and the English of American Jewish worship services. Moreover, his proud assertion of the traditional Jewish doctrine of Jews as the Chosen People put him at odds with the universalistic orientation of Reform Judaism.

Nor was he attracted to the behavioral requirements of Orthodox Judaism. He never embraced the norms of Jewish ritual behavior, including, most critically, endogamy. Gertrude, his second wife, was a practicing Roman Catholic. Christmas was celebrated in the Schoenberg home. He acquiesced in giving his children a Catholic school education. When asked about his thinking regarding the religious orientation of his children, he offered a pragmatic reply: his second wife was much younger than he, and therefore, the children would likely have many more years of contact with her than with him; so her religious connection with them ought to prevail.

For Schoenberg, Jewish identity was made manifest in three domains: (1) his proud self-assertion, made all the stronger by its being an act of defiance against the Nazis; (2) his passionate concern for Zionism and Jewish rescue; (3) a turn in his music to Jewish themes and Jewishly-inflected spiritual concerns.

Schoenberg’s attempts to benefit the Jewish people politically claimed much of his attention during the dozen years of the Nazi nightmare. He proposed the creation of a new Jewish movement. He also offered to head it, his qualification being that he was inured to facing obstacles and triumphing through sheer hard-headedness.[32] In a letter to the Zionist leader Jacob Klatzkin in 1938, he wrote that he had largely abandoned composition for the past two years, focusing instead on his Zionist conscious-raising efforts. That same year, after being prominently attacked in the Nazi exhibition, Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music), Schoenberg announced his “Four-Point Plan for World Jewry.” The plan called for the unification of Jewish efforts in a single organization which would focus its efforts, not on the ineffective tactic of boycotting Germany economically, but on the rescue of imperiled Jews and the securing of an independent Jewish state in Palestine.[33]

These efforts bore no fruit. Schoenberg was not even able to find a publisher for his plan. But he did have some success in helping individual Jewish refugees to become established in America.

Among the rabbis he engaged in his round of political and humanitarian outreach efforts was Jakob Sonderling. This connection was to lead to the composition of Schoenberg’s only work intended for the synagogue, his setting of the “Kol Nidrei” prayer.

Rabbi Sonderling had a lifelong interest in enriching religious life by means of art. His musical inclinations were doubtless present since childhood. His household had ties to the Hassidic-Jewish subculture in Silesia. Hassidic Judaism emphasizes the religious value of singing. It holds in high regard both the setting of prayer texts to melody and the practice of singing wordless “niggunim” (vocalise compositions) in religious contexts.

Rabbi Sonderling had gone far since his childhood, geographically, intellectually and professionally. He served as a Feldrabbiner in the First World War, then occupied a prestigious pulpit as preacher in the temple of Hamburg, the original Reform Jewish congregation in Germany. In 1923, he immigrated to America, where he served a traditional congregation in Chicago, before settling in Los Angeles in 1935. Although his religious affiliation was liberal, during his American career, he did not affiliate with Reform Judaism, the American parallel to the German liberal stream within Judaism. Rather, he served as the rabbi of the Society for Jewish Culture–Fairfax Temple, a congregation with a humanistic orientation, independent of the denominations of American Jewish life. One reason why Rabbi Sonderling may have declined to join the Reform rabbinical group is that he was an early Zionist, before the American Reform movement as a whole had come around to supporting Zionism. Another reason for his decision to remain independent of the Reform rabbinate may have been that he had an attachment to the mystical side of Judaism, which was frowned upon within the Reform movement of the day.

In 1938, Rabbi Sonderling engaged Schoenberg to composing a setting of the “Kol Nidrei” prayer for the Day of Atonement services. This was not the first time Rabbi Sonderling had engaged a contemporary composer to enrich the musical repertoire of synagogue life. Less than a year earlier, he had met the émigré Austrian-Jewish composer Ernst Toch, a member of Schoenberg’s modernist circle.[34] Toch had received word of the death of his mother, and in an act of filial piety, he went to Rabbi Sonderling’s synagogue to recite the traditional mourners’ “kaddish” prayer. The rabbi established a rapport with him, invited him to bring his daughter to the upcoming family Hanukkah celebration and asked him to compose some simple music for the children’s performance. Toch declined the request to compose the music. Nonetheless, the idea resonated with him, and he made a counteroffer, to supply a work for the upcoming Passover celebration. Rabbi Sonderling enthusiastically agreed and provided the libretto for Toch’s composition, The Cantata of the Bitter Herbs. It received its premier performance at the synagogue over Passover of 1938. All this was a few months prior to Rabbi Sonderling’s outreach to Schoenberg.

Schoenberg accepted the rabbi’s invitation. This was not a foregone conclusion. Five years later, Schoenberg declined an invitation from Cantor David Putterman, of the Park Avenue synagogue in New York City, to compose a setting of another prayer from the standard liturgy. The prayer, “Mi Khamokha”, might well have appealed to Schoenberg, because it is based on Exodus 15: 11, whose theme is the rejection of idolatry. The prayer proclaims that none of the false gods that people worship can bear comparison to the true God. Nonetheless, Schoenberg did not respond to the cantor’s invitation. And yet, this time, he said yes to the rabbi. This calls for explanation.

Perhaps Schoenberg felt that the networking opportunities were too valuable to pass up. Part of his effort to rescue friends and colleagues, eager to flee the Nazis, was lining up people to give affidavits to the U.S. State Department. In these affidavits, American citizens vouched for the upstanding character and unobjectionable political affiliation of the would-be immigrant. Critically, the people giving the affidavits offered the would-be immigrant either employment opportunities or a pledge of charitable support. The U.S. government would only admit a refugee on the assurance that he would not become a public burden. This requirement sharply limited the number of affidavits that any one person of average financial means could send. Schoenberg probably hoped to work through Rabbi Sonderling to expand the number of people willing to supply such affidavits, and thereby save the lives of people in the composer’s circle.[35]

In addition to his humanitarian concern, Schoenberg also used the commission to work through a spiritual dimension of his return to Judaism. Here, it is important to clarify the specific function of the “Kol Nidrei” prayer. It is a formal ceremony, performed at the very beginning of the Yom Kippur eve service, i.e. the opening of the entire holiday. The cantor leads the congregation in a solemn recitation, asking God’s forgiveness for any vows the people have made but were unable to fulfill.

Anti-Semites throughout the ages have pointed to this text as “proof” that Jews were inherently untrustworthy. Internalizing that criticism, many Liberal congregations in Germany and Reform congregations in America had abolished the Kol Nidrei prayer. Others modified it, keeping the popular and identifiable melody but substituting radically different texts for the traditional formula. In some synagogues, the melody was presented as a wordless vocalise.

Schoenberg was initially dubious about working on this prayer, because of his moral scruples. But instead of rejecting the rabbi’s request out of hand, he studied the history of the prayer. He learned that it originated to provide a vehicle allowing Jews to return to their original faith, after they had taken oaths to become Christian. The oppression of Jews in the Middle Ages was at times so severe that many Jews converted out of fear or duress. The Kol Nidrei was a prayer designed to speak to them in their emotional distress and allow them to reclaim their Jewish identities.

A few years after having created the work, he explained how he had worked through his initial objections. In a letter to Paul Dessau, Nov. 12, 1941, he wrote:

At my request the text of the traditional “Kol Nidrei” was

altered, but the introduction was an idea of Dr. Sonderling’s.

When I first saw the traditional text, I was horrified by the

“traditional” view that all the obligations that have been assumed

during the year are supposed to be cancelled on the Day of

Atonement. Since this view is truly immoral, I consider it false.

It is diametrically opposed to the lofty morality of all the Jewish

commandments. From the very first moment I was convinced

(as later proved correct, when I read that the Kol Nidrei originated

in Spain) that it merely meant that all who had either voluntarily

or under pressure made believe to accept the Christian faith (and

who were therefore to be excluded from the Jewish community)

might, on this Day of Atonement, be reconciled with their God…[36]

In his 1941 reflection, Schoenberg added the category of those who had voluntarily become Christians to the set of people who had been pressured into converting. This could well have been self-referential. In his setting of the Kol Nidrei, Schoenberg created the music to the text of his own life decisions.

Schoenberg’s earnestness in accepting the project is reflected in the close attention he paid to the text Rabbi Sonderling presented to him. Schoenberg worked together with the rabbi in revising the text to produce a more concise libretto. The result was very much a collaborative effort, and thus, reflects Schoenberg’s thinking at the time. Interestingly, the final version of the text contains a reference, unusual in the non-Orthodox liturgy of that era, to a mystical doctrine:

The Kabbalah tells a legend. At the beginning God said,

“Let there be light!” Out of space a flame burst out. God

crushed the light to atoms. Myriad of sparks are hidden in

our world, but not all of us behold them. The self glorious,

who walks arrogantly upright, will never perceive one; but

the meek and modest, who walks with eyes downcast, he

sees it—“A light is sown for the pious”.